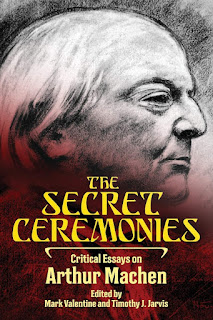

The Secret Ceremonies: Critical Essays on Arthur Machen

Edited by Mark Valentine and Timothy J. Jarvis

2019: Hippocampus

The Secret Ceremonies recapitulates the decades-long activity of Machen readers and collectors to inspire a broader engagement and appreciation of the author. That task has been accomplished. The writers featured in Secret Ceremonies deserve the credit. And the book itself is a pleasure from cover to cover.

Below are excerpts I made from several selections in the book that struck me, and I wanted to preserve in my commonplace book.

Arthur Machen: The Evils of Materialism

S. T. Joshi

....dominant theme that unites them, it is the constant contrast between mundane modernity and the hoary past—a past that is simultaneously terrifying in its primitivism and awesome in its suggestions of intimate, symbolic connexions with the essence of life and Nature. However brutalised modern people are by the dominant materialism of the age, their sense of spirituality can well up in spite of themselves in the practice of ancient rituals.

["A Fragment of Life"] ....The exquisitely gradual way in which the stolid bourgeois couple, Edward and Mary Darnell, slowly awaken to their sense of wonder and abandon London for their native Wales is one of Machen's great literary accomplishments. Amidst all the mundane details of the small-scale social life of the Darnells, we receive hints that their love of beauty has not been entirely destroyed, as it has for so many who live too fully in the modern world.

Arthur Machen: The Pagan— His Work and His Personality

Geoffrey H. Wells

....For to him all life, all existence, is but a hieroglyph, symbol of a hidden glory; and all art is but the flickering candle of the human soul, stumbling in the black void of "transitory, external surfaces." "He dreamed in fire; he has worked in clay," Arthur Machen writes of the boy he was, and indeed he views all the seeming actuality of this world as but the expression in clay of a secret reality of splendid flame. Again and again he has striven to rend the veil and convey to us something of his vision, and here and there, at precious moments, he has succeeded. But ultimately he accepts the hieroglyph: "at the last, what do we know?"

The City, the Vision, and Arthur Machen

Godfrey Brangham

.... Machen's daughter recalled the infinite pains he took over his writings in his later years, discarding script after script as he sought the right word or phrase to kindle beauty on the page. Within the framework of the plots he devised, Machen achieved a high level of musicality, a level that few other authors ever managed to attain. The city and his vision of it produced literature that has endured the passage of time. Given the rarefied atmosphere of the landscape he inhabited throughout his life, it is perhaps fitting to end with an acute if plaintive observation made by one of his admirers, the poet John Betjeman: "If only one could see through the eyes of Arthur Machen."

New Arabian Frights: Unholy Trinities and the Masks of Helen

Roger Dobson

....The status of fictional characters is hardly ever questioned by us: we simply accept the convention that the world of fiction is worth exploring because we know we shall be entertained, informed, and diverted. On the simplest level, when there is already a good deal in the world to weep about, beings that have never existed have the power to make us cry.

A Glow in the Sky: Some Observations on Machen's Style

Jon Preece

....There is a vigour in Gibbon's style that is entirely lacking in most Victorian prose (such as the Hardy passage quoted above). It is clear, informative, direct, and affirmative. There is a sharp dash of humour, too. All these elements are present in Machen's mature prose style. By looking to the past—to the eighteenth century—Machen had inadvertently stumbled upon his way forward as a prose writer.

The Secret and the Secrets: A Look at Machen's Hieroglyphics

John Howard

....Machen's other great connected fictional themes, those of "sorcery" and "sanctity," also have their place in Hieroglyphics. Each is "an ecstasy, a withdrawal from the common life" (CF 2.185). For Machen this meant true reality. And while his fiction tends to deal with the "sorcerous" side of reality, the dangerous and destructive side, in Hieroglyphics he chooses to encounter the "sanctified"—the life-enhancing and constructive—in a theory of literature which uses ecstasy as its starting-point and distinguishing feature.

....that true literature, through the hierophantic author, is often, through symbols, seeing and conveying reality as it is.

....The whole reason for the book is the question, What distinguishes true literature from mere writing, even if interesting writing?

....Hieroglyphics is as much a book about looking for an answer as it is about providing an unassailable answer in it

....But Machen did consider many of the works of one woman, Mary E. Wilkins Freeman, to be fine literature. A New England author little known today except for her ghost stories, for over thirty years from the late 1880s she was a fairly prolific....

....Machen knows the books that he likes and therefore calls them true literature. He then fits them into his literary theory of ecstasy, as they contain that which defines and makes fine literature.

....taste is what is subjective, and not art. Thus art is there, and has nothing to do with popularity and enjoyment, "classic" status, and so on.

Of Sacred Groves and Ancient Mysteries: Parallel Themes in the Writings of Arthur Machen and John Buchan

Peter Bell

....Buchan's sense of classical doom is well defined by Greig: "That sensitivity to the incalculable, sometimes uncanny deus absconditus, the God—to the ancient Greeks the gods—behind Nature in all her moods—Benigna and Maligna—pervades the short stories" (viii). Both were clergymen's sons: Buchan's father a minister of the Free Church of Scotland, Machen's father, and grandfather, Anglicans. Christianity exerted a powerful force on the young writers, sitting perhaps uneasily with Celtic and classical paganism; yet this very tension weaving rich strands in the tapestry of their visions. Each writer's response, however, was distinctive: all his life, Buchan felt a conflict between his mystical, pagan empathies and his Calvinist conscience; whilst Machen, enamoured of the mystic glory of ritual, reinforced his faith, gravitating towards High Church.

....To these formative influences must be added the zeitgeist of fin-de-siècle England, a cauldron of seething, innovative ideas, linked by a rejection of convention and fascination with the Unheimlich. This was the era of Symbolism and Decadence, of Oscar Wilde and The Picture of Dorian Gray, of Celtic revivalism, of W. B. Yeats and William Sharp, whose Celtic fantasies began appearing in 1895 under the pseudonym Fiona Macleod. Lane, through 1894–97, was publishing Aubrey Beardsley's and Henry Harland's Yellow Book, an eclectic mix of the decadent, fantastic, and aesthetic; whilst in the Keynotes series he was introducing controversial, esoteric works, the fifth being "The Great God Pan."

....Stevenson's paramount influence upon the two can be seen in the structure and style of Machen's The Three Impostors and Buchan's The Runagates Club, and is evident in the weird content of various tales, with madness and mysterious drugs prominent in the trend of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.

....Like Machen, Buchan approaches landscape with a mixture of reverence for its magnificence and awe at its secret terrors.

....Buchan develops his story differently from Machen, and is ultimately less effective. The power of Machen's horror lies in his restriction of information, allowing the reader's imagination full rein. The peril of the little folk is the greater for being indirect, understated, conveyed by subtle glimpses, creating "an aura of menace and hideousness about them, in a masterpiece of macabre allusiveness" (Valentine 41). Buchan builds up his terror subtly at first, recounting the ramblings of a shepherd, torn between religious mania and alcohol as a salve against the powers of darkness, obsessed with the struggle between God and the Devil. He seeks to deter Gray from the area, indicating a hill with a Gaelic name meaning the "Place of the Little Men": "I saw something in the first year o' my herding here which put the terror o' God on me, and makes me a fearfu' man to this day" (ST 90). He tells of sheep ravaged in ways no poacher would use; and "stories o' faces seen in the mist, and queer things that have knocked against me in the snaw, wad ye believe me?" (ST 88). When these accounts are dismissed as old wives' tales by the scholar, the shepherd reminds him "ye're no in the toun just now, but in the thick of the wild hills" (ST 88). The mystery is dissipated, however, by the long, graphic account of Gray's experience at the hands of the Picts, who capture him and try to suborn him into perpetrating a sacrificial killing of a woman; here Buchan moves into adventure story mode. Gray, having escaped Houdini-like from bonds, returns in a spirit of scientific zeal, leaving an unfinished journal, rather in the manner of Gregg, setting out upon his "final trial and encounter" (CF 1.399) with the "Little People."

....To conclude, a comparison of Machen and Buchan reveals certain common themes, ideas, and motifs: madness and split personality; books of occult lore; sacred groves and ritual; Roman survival; the spirit of Pan; lost races and fairy folk; numinous landscape; and mystical experience. Much stemmed from similar immersion in Celtic, classical, and Christian lore, and from the two writers' intimate, nostalgic relationship with their rural roots, in an era of threatening modernity. They cannot, however, be divorced from the zeitgeist; similar concepts can be found in many late Victorian and Edwardian authors, some of whom had signal influence upon the aspiring young writers.

The Impossible History: Machen's "A Fragment of Life"

John Howard

....What seems important is really of no importance, and we ignore the things of true importance at our peril, or at least, our impoverishment.

....His new interests help to bring him closer to his wife. This is made plain throughout the narrative—even as Darnell himself cannot articulate it in words—and is symbolised by the dream he keeps on having to awake from. As he starts to open up to his wife, she wishes to know more and to understand—and to journey with him.

....in the revised chapter he strains as ever to express that which cannot be expressed, and even if the result was still far from successful in his eyes, Machen harnessed this inherent inability to point towards what he wants to say. This is appropriate in a story of yearning and transmutation.

....In an apparently disjointed and rambling story Machen illustrates the dislocations and contradictions of real life, together with much dark comedy. Machen undermines realism for his own ends: to show that the mundane actually masks reality—or what should be true reality. And it is when the covering slips—as Machen must allow it to do—that the paradox is invoked. The disjointed aspect masks a seamless quality: the transition from "reality" to Reality.

"All Manner of Mysteries": Encounters with the Numinous in The Cosy Room and Other Stories James Machin

...."The Lost Club," with its clear debt to "The Suicide Club," marks the beginning of one of the prevailing features of Machen's output for the first half of the 1890s: that of playing the sedulous ape to Robert Louis Stevenson.

....Machen always regarded as the blight of modernity on human life and its degradation of the imagination with the quotidian.

the hazing of the reader with disparate glimpses of an only obliquely delineated whole is executed with really extraordinary legerdemain, resulting in a seamless unity of effect. It is, in short, a masterpiece.

....The unfortunate corollary of approaching Machen through his influence on subsequent weird and horror fiction is that there is often a sense of disappointment when one moves on to his later, less-celebrated, writing and finds it so different in tone: the Stevensonian exuberance of the strange, exotic 1890s replaced by a journalistic, anecdotal, all-too recognisably twentieth-century voice.

....one could argue that "N" is Machen's riposte, almost at the end of his career, to one of its opening salvos, "The Great God Pan": both stories rely on a fragmentary, nonlinear structure, with multiple characters offering oblique perspectives on a central, unresolved mystery. However, where the latter plunges the alarmed reader into a netherworld of weird gruesomeness, in the former Machen uses accomplished sleight of hand to instead leave the reader with a genuine sense of quiet revelation. Machen once famously complained that his "failure" as a writer was one of translating "awe, at worst awfulness, into evil" (FOT 123). "N" is, however, the very refinement he sought for, the literary equivalent of an alchemical transmutation of evil into awe.

Some Thoughts on "N"

Thomas Kent Miller

....his predominant theme ("the intermingling of this world and another of far vaster significance," as Machen biographer Mark Valentine puts it....

....Howard, paraphrasing critic Joseph Wood Krutch, says that "Machen had only one main plot in his fiction, that of 'rending the veil'"

....we find that most dictionaries do not even include the word perichoresis, and those that do define it strictly in the Christian sense of the penetration and interconnectivity of the three divine persons of the Trinity.

....that perichoresis was also employed in specialised occult circles, such as the Order of the Golden Dawn (with which, of course, Machen had been affiliated for a time), to mean the interpenetration of dimensions or of the connecting principle between matter and spirit.

....When one considers that this notion of perichoresis/interpenetration/ boundaries is at the heart of not only most of Machen's stories but most of those in particular that have gone on to influence so indisputably the development of the supernatural horror or weird genre to this day, there may well be much truth in Howard's conclusion that "the theme of 'boundaries' is central to Machen's work," to the degree that it can be considered "Arthur Machen's lasting contribution to literature" ("Interpenetrations" 39).

....a door is probably the simplest archetype or metaphor for the presumed interconnection of here and there—that is, of ingress and egress through or across boundaries, as Howard puts it.

....his later 1930s-period pseudo-journalistic stories in which he incorporates himself as a journalist (his common wartime device, unused for fifteen years)

....In "N," he lays out his vision most succinctly and creates a kind of roadmap with which to navigate his literary apparatus of suggestions, implications, inferences, hints, and sly winks that were so fundamental to all those stories that he knew fully well by then, by 1935, were already considered his classics.

When sitting down to write "N," he likely chose Stoke Newington as the setting because of its real-life historical connections to Edgar Allan Poe and the Manor House School that Poe describes so well in "William Wilson," a story that Machen presents as a sort of Rosetta Stone to reflect light on his own tale. In fact, it would not be far-fetched to imagine that "N" is a kind of sequel to Poe's story inasmuch as "N" owes much to "William Wilson," not only in setting but in tone.

"It Is Getting Very Late & Dark": Machen's Last Fiction

Mark Valentine

....All his life Machen held to the idea that the visible world is only a façade, a symbol of a far greater and stranger world beyond. That accounted, he thought, for the sense of mystery that some places possess: at these, the veil is thinner and it is possible to glimpse a different domain.

....Arthur Machen's considered verdict on this book was given in a letter to A. E. Waite of 16 November 1936: "I believe you are right in thinking that there are hints or indications of new paths in 'The Children of the Pool':—but it is getting very late & dark for treading of strange ways" (SL 59). He was always a modest man, reluctant to acclaim his own work, but between the lines of this comment it is possible to see a quiet pride that he was still able to advance original ideas and pursue curious, unexpected paths of thought.

Jay

27 August 2019

No comments:

Post a Comment