Readers who are unfamiliar with the collection may prefer to read these notes only after reading the stories.

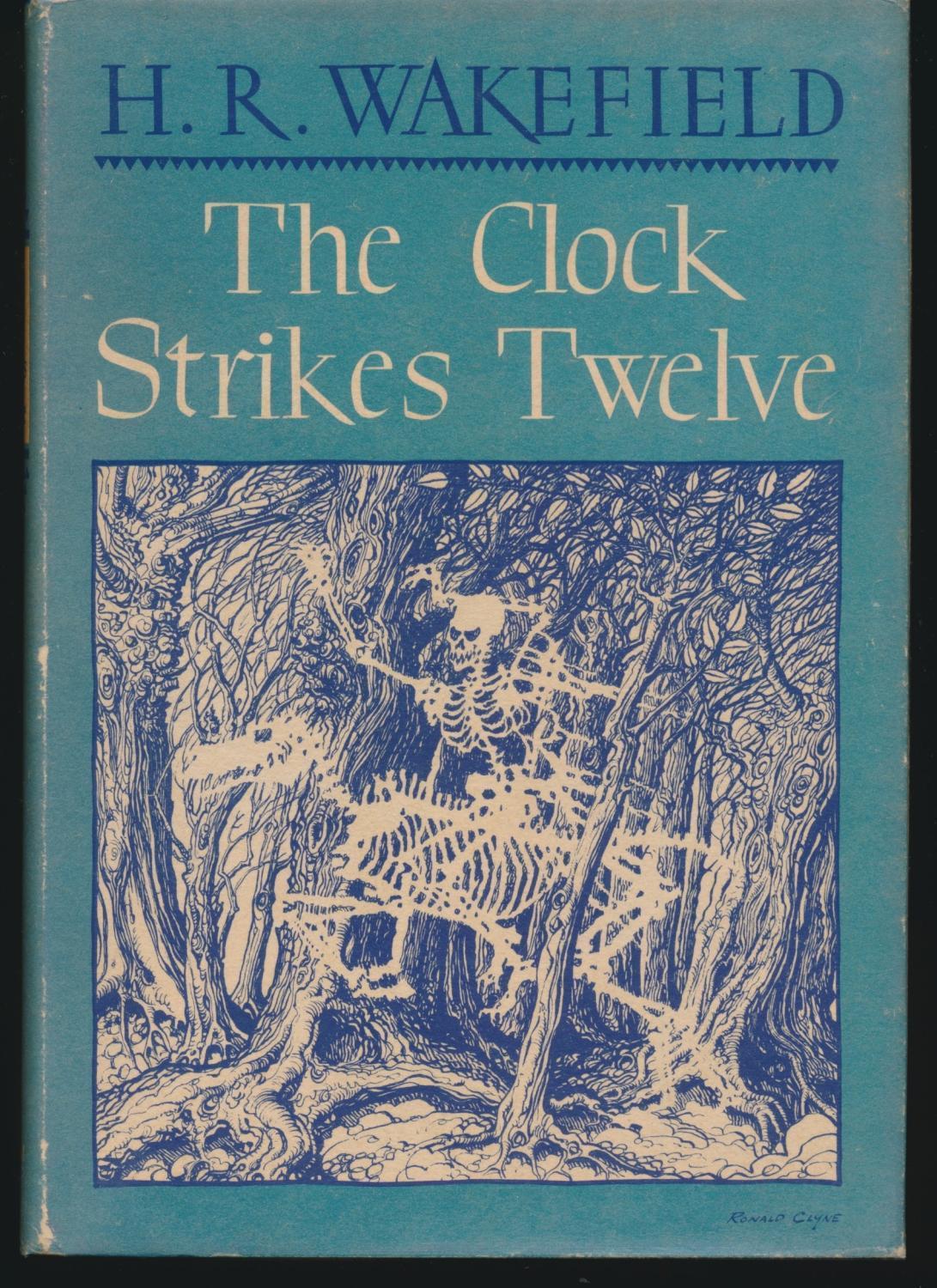

Two years ago I read most of the short stories in The Clock Strikes Twelve, and posted about them here. Last week, I returned to the collection.

Not Quite Cricket

' "There they are, both of 'em!" he yelled. "Sam's come to see the play, bloody face and all!"

"Not Quite Cricket" is a well-told rural horror story centered on the cricket rivalry of two men and their villages. But this is not a Hornung or Wodehouse cricket yard. Wakefield does a fine turn depicting sudden death in sport, pulling in peg legs, gypsies, and a village idiot with second sight. There is nothing light-hearted outside the framing prologue; this is life depicted as lived for mortal stakes.

A Fishing Story

An Irish fishing story, beautifully evoking a troubled landscape.

A fish rose, head and tail, a little ahead of Tranion's fly. He reeled out, took in the slack, and dropped the fly in the widening swirl.

It didn't rise again and Meynel's eyes wandered. Tranion had flushed a small gaggle of geese, which gained flying height, made formation, and sailed seawards. A curlew wailed happily by. A brace of teal, wing to wing, swished towards them, saw them, changed direction, and were lost in a sunbeam. A small bird came to a rock, flicked his tail, and made a tiny, definite sound. A twite, perhaps, thought Meynel; I rather think so. What a long, lovely, desolate land this is, he thought, and hardly a man to be vile. But there was evidence of his existence in the footed stacks of peat where the turf had been neatly shaved down. Directly in front of him were two rough stone pillars, one on each side of the Glady, and nothing connecting them.

'Was that bridge destroyed in the Bad Times?' he asked.

The gillie stared at it for a moment.

'Well, it was not,' he said. 'That wasn't the way of it.'

'It just collapsed, did it?'

'Well, that's true, it did; that's how it was.'

'Just fell in?'

'Well, it fell in, it did.' He paused. 'But there was a man on it when it fell,' he added. 'It was rotten, you see.'

'All the bridges over the Glady are rotten,' said Meynel with feeling. 'A foot wide, no hand-rails, and full of gaps; horrible wobbly brutes. I hate the sight of them.'

'But,' said McBrain, 'those others are foine, stout bridges compared with the way this one was.'

'What happened to the chap who fell in? It must have shaken him up a bit.'

'It must have done that. There's no doubt about that at all.'

'Could he swim?'

'He could not.'

'How did he get out, then?'

'Well, that man never got out.'

'He was drowned!'

'He must have been drowned surely.'

'But you must know, McBrain! His body must have been found.'

'No, that man's body was never found.'

I Recognised the Voice

"I Recognised the Voice" is one of the stranger stories in The Clock Strikes Twelve.

Two men, Goran and Lefanu, spot each other at their club.

Goran had the very queer sensation that they had long been acquainted, as if they had met in some previous incarnation. An absurd idea, but how otherwise to explain this feeling for one with whom he had never exchanged a word, never seen before to his knowledge?

When they sit down over drinks, Lefanu reveals he is somewhat clairvoyant, having "learnt some odd things in Tibet, the air breathes magically there." Each man tries unpicking the tangled skein of their connection. This being a Wakefield story, adultery and murder play a part.

Red Feathers

Bloody hell, "Red Feathers" is a masterpiece of some kind: misanthropy first and last. But also a masterpiece of cold feet about shooting animals and about having feet of clay about the prospect of marriage to hell-whelped "steel-and-concrete harpies."

Happy Ending?

Young student of behaviorism Jonathan Turtell rents a bed- sitting room at 84 H—— Street.

As for the other denizens of Number 84, Jonathan had no concern with them; but he vaguely hoped the person next door didn't snore, for he could hear him moving about and the wall seemed rather thin.

Jonathan that very night begins having consecutive dreams related to that next door room.

....there was, of course, always the possibility that the Universe was fundamentally irrational and that such phenomena were merely modes of its unreason; that Nature sometimes acted in such a way that man could not frame laws to interpret that action. This possibility was highly unpalatable

Wakefield is happiest grinning as he examines his characters like Petri dishes through the microscope.

Jonathan's régime was regular and austere. He had a light breakfast at an A.B.C. shop, worked from nine to one. Had a light lunch at an A.B.C. shop, worked from two to six. Had dinner at a Corner House. Usually went to a movie afterwards, for the reactions of the multitude were of huge psychological value. Walked back to 84 and went to bed.

The real mirth Wakefield conveys in relating facts of everyday life about his protagonists is only matched by his enjoyment of how they suffer his Savonarola-scale authorial chastisements.

Death of a Poacher

"Death of a Poacher" would have made a memorable episode of "Rod Serling's Night Gallery." Zoologist Sir Willoughby Mantlet, Bart., has returned shattered in mind and body from Africa. A friend of his enlists our narrator for an informal diagnosis during a country house weekend hosted by the Bart.

Sir Willoughby might have scheduled his appointment in Samarra in Africa, but it becomes clear to his guests that he knows the final encounter is now at hand– and that it will be mortal.

He gives the narrator the picture:

'I had not been long in this region before I had reason to believe it housed a secret. Briefly, there was a conviction amounting to certainty that some strange animal had there its habitat. This belief was held by the white population, though they were disinclined to discuss the matter with strangers. The Masai were elusive and enigmatic about it, as only savages can be....'

[....] To an ardent zoologist the possibility of being the first to discover an animal unknown to science was irresistible....

The usual country house rigamaroles ensue over several days, including rumors of poachers and sounds of distant gunfire.

It was impossible to concentrate; somehow [Sir Willoughby's] psychic malaise communicated itself to me. It may sound fantastically exaggerated, but I felt in the presence of some thing of darkness. I would have done anything to help him, but what was almost incipient panic urged me to be away.

The final encounter is a showdown at night in open country on the estate.

....I think we both saw it at the same moment. It was huge and it was crouching over something stretched out beneath it on the margin of the stream. It looked up and its eyes were slanted, orange, and utterly evil.

"Death of a Poacher" is a belated story of colonial life coming home to roost. It does not attempt the heights of "Pollock and the Porroh Man" (1895) or "The Recrudescence of Imray" (1891), but it sharply demonstrates the knowledge that there is no UK "moat-defensive" (Clute) untouched by empire's consequences.

From the Vasty Deep

"From the Vasty Deep" is a pitch-perfect story of ambitious theme and scope.

Rival leading men Alistair Brayton and Sir Rex Beaumont find themselves together on holiday at Algiers, a city of fine hotels amid streets filled with "septic beggars and precociously lewd small boys."

Brayton bribes a sand-diviner to predict Beaumont has a year to live, a "catty" move even in "that logically lawless profession."

Within a year Beaumont is dead, at the end of a world cruise meant to help him forget the seer's prophecy.

Unluckily he went alone save for one companion, John Barleycorn. That boom comrade and he became inseparable. 'Why not,' he told himself, 'if I am doomed!' Of course he got no better. In fact he threw himself overboard on the last night before the ship reached Southampton, and though they searched for a while, they could not find his body.

Brayton, who could not confess his joke when Baumont was alive, certainly cannot admit it after the suicide for fear it will end his career.

He could not get Rex out of his mind, especially as he began dreaming about him and what was worse, always the same dream. He was standing on a beach gazing out to sea over some rocks. The sea was breaking lightly over the rocks and he was looking for something he knew he did not want to see. He stared hard, watching the lift of each small wave. Presently he saw something white rise on a crest, surge forward, and disappear. There it was again, a bit nearer this time, and the next time and the next. And then whatever this was reached the rocks. He wanted to run away but he could not move. Then he saw it climb up on the rocks and come toward him and it was something like a naked man, only there was a difference. For instance where the face should have been, he presently could see, was the big ochre shell of a crab, and he could see the claws moving, and that was the worst of all....

The final pages of "From the Vasty Deep" are a tour de force depiction of Brayton's ordeals during rehearsals and the first night of his star turn in Macbeth:

The back parts of theatres during the throes of rehearsal of a big play like Macbeth are crowded, scurrying places; chaos to the uninitiated, but really that odd, motley section of humanity on the move about its business is a good example of organised division of labour. Brayton was, of course, quite at home in this come-and-go and could perfectly distinguish the wood from the trees, the combined effort from the atoms composing it.

Yet one of these 'trees' began to worry him. Whether it was in a group of scene-shifters, or Scottish Noblemen, or the orchestra, or any grouped bodies contributing to the enterprise, an intruder was sometimes to be seen furtively lurking; very furtively, for the moment Brayton got him properly in his gaze, or rather just before he succeeded in doing so, he at once dissolved and disappeared, presently to reappear elsewhere. During one rehearsal he saw him for a second watching from the Royal Box. The curtains of the box were of light ochre silk and Brayton noticed a certain resemblance.

Of course his colleagues noticed something was the matter with Billy Bennett and whispered and wondered, but they had to confess he had never acted better. He was word perfect and never more moving and intense; the tortured Thane and he seemed absolutely one in spirit indomitably defying all the legions of Earth and Hell and Heaven.

For the first night he plugged himself with as much Scotch courage as he dared, and Dulcinea Delavere, the Lady Macbeth, turned up her nose when she accepted his bouquet and hoped for the best. It certainly was the best; he had never given such a terrific performance, in spite of, perhaps partly on account of, the fact that there was someone who had no business to be there, standing for a flash in the shadows behind the weird sisters, and then entering for a second with Duncan's retinue, and just visible out of the corner of his eye as he tried to seize the phantom dagger. But he was very near breaking-point in the banquet scene, for when he and his lady were surveying the assembled guests and the ghost of Banquo should have entered, it was not Banquo who came in, but someone Brayton had seen terribly often coming towards him across the rocks.

'Which of you have done this?' he cried, and pretty well everyone in the audience felt a quick, damp fear break out on them at the way he spoke that mighty line. Dulcinea, who was watching his face as he spoke it, says she knows she will never forget it, but hopes very much she is wrong....

* * *

As part of returning to The Clock Strikes Twelve, I decided to sample a few critical opinions about H. Russell Wakefield. Assessments were mixed.

Mike Ashley summed him up briefly in Encyclopedia of Fantasy (1997):

....noted for his Ghost Stories, some of which rank alongside those of M R James, with whom he is sometimes compared. Although most of his stories are formulaic they are well crafted and frequently atmospheric, and often feature vengeful ghosts (see Vengeance). Wakefield was first inspired to write by an experience he had at a reputedly haunted house in 1917; this resulted in "The Red Lodge", in his first volume They Return at Evening (coll 1928).

Richard Bleiler in Horror Literature through History (2017):

....Wakefield recognized that hauntings did not necessarily need to involve medieval cathedrals and manuscripts or the English public schools; indeed, hauntings could occur in the twentieth century and did not need to involve the English upper classes. Wakefield thus occasionally made use of the traditional English country estate in such works as "The Red Lodge" (published in They Return at Evening), but his settings included golf courses ("The Seventeenth Hole at Duncaster" in They Return at Evening), and could involve even used cars and American gangsters ("Used Car," 1932)....

Jack Sullivan in The Penguin Encyclopedia of Horror and the Supernatural (1986):

.... taking James's emphasis on tautness and economy a few steps further, without the doting descriptions of old architecture and often without a denouement. The

cold efficiency of his endings—sometimes consisting of a swift, brutal line or two—can be deliciously shocking or simply puzzling. He was not as richly atmospheric or consistently satisfying as James, but his best work has a percussive power that is unique and memorable.

Jess Nevins, in Horror Fiction in the 20th Century Exploring Literature's Most Chilling Genre (2020), salutes Wakefield's competence, but goes on to quote Brian Stableford to the effect that Wakefield "took up where M.R. James left off in extending the core of the British tradition through the period between the wars."

Wakefield, part of a postwar levy of professional writers, had a wide curiosity about motivations of men and women from all classes. "Lucky's Grove" and "The First Sheaf", two of his finest stories, are acutely non-Jamesian in point of view. Other specters are linked to domestic crime. In many ways, they share themes explored not by M. R. James but by E. F. Benson. Benson built his career as a fiction writer on comedies and melodramas of domestic malice and rural-urban feudal-bourgeois boundary clashes.

The most acidic Wakefield critic today, S. T. Joshi, writes in Unutterable Horror: A History of Supernatural Fiction (2014):

[....] Lovecraft enjoyed several stories from his first two collections, but many of them are undistinguished, such as "The Red Lodge," a routine story of a house haunted as a result of murders committed in the past; "'He Cometh and He Passeth By,'" a shameless rip-off of M. R. James's "Casting the Runes" and clearly meant to portray the moral evil of Aleister Crowley; and "The Seventeenth Hole at Duncaster," in which a wood near a golf course apparently has evil properties, for no ascertainable reason.

[....] Some later tales reveal moments of interest.

[....] Some of Wakefield's later work does exhibit an engaging misanthropy (and, perhaps less appealingly, also misogyny), but overall his work is not nearly as meritorious as his small legion of ardent followers appear to believe.

To say that the horrors depicted in the sublime "The Seventeenth Hole at Duncaster" have no ascertainable motivation is willful critical blindness.

* * *

Jay

20 April 2023