"On Skua Island" (2001) by John Langan is a masterful folk horror mummy adventure.

It begins during a house party, guests stuck in the beach house due to a coastal storm. The members of the household are part of the U.S. academic and financial meritocracy.

The talk turns to the dearth of mummy horror tales:

"The mummy is different," I replied. "It's a relic from a different time, the imperial age, from when the sun never set on the British Empire. Has anyone read any of the original mummy stories, the ones Arthur Conan Doyle wrote?" Only Bob nodded. "I shouldn't call them the original stories; I don't know for sure whether they are or not. I assume they were among the first. Anyway, Conan Doyle's mummy is very different from what we're accustomed to when we hear that name; at least, from what I think of. His mummy is a weapon. There's an obnoxious student of obscure foreign languages at Oxford who buys one that he keeps in his apartment for use against his enemies. He can read the spell that animates the mummy and sends it to do your bidding, which in his case usually involves disposing of the latest person who's annoyed him...."

"This is all very nice," Kappa said, "and very educational, I can assure you. But isn't it a bit off track? We were talking about things that actually had happened to people, not movies and books."

Bob nodded, and Jennifer said, "You're absolutely right, Kappa, we were talking about actual events."

"So," I said, glancing round the company gathered there in the living room, my eyebrows raised for effect, "does anyone have a mummy story they'd care to share?"

There was a pause during which the wind fell off, and then a voice said, "I do."

We looked about to see who had spoken, and our eyes settled on Nicholas, who had been introduced at the start of our stay at the Cape house as an old friend of Bob's from Harvard and who had maintained an almost unbroken silence in the five days since, departing the house for hours at a time on walks whose destination he shared with no one, but which appeared to take him inland, away from the beach and the winter-angry ocean. His face was buried under twin avalanches of white hair, one descending from the tangled mass crowning his head, the other rising from the tangled mass hugging his jaw, but his hooded eyes were a pale bright blue that I should have described as arctic. For dress, he favored a pair of worn jeans and a yellowed cable-knit sweater, which he supplemented with a long grey wool coat and boots that laced up just short of his knees for his jaunts outside. In reply to a question Jennifer had posed our first morning there, while Nicholas was out, Kappa had informed us that Nicholas was an archaeologist whose particular interest was the study of the Vikings, which was the basis upon which his friendship with Bob had been founded when they met at Harvard. Although they had maintained contact over the years, it was not uncommon for Nicholas to disappear on some expedition or another for months at a time, and occasionally longer, which was part of the reason Kappa assumed he never had married. He did not speak much: this we had witnessed ourselves as Jennifer, who prides herself on being able to have a conversation with any living human being, availed herself of every opportunity to ask Nicholas questions, about himself, his career, what he was engaged in currently, that he answered in monosyllables when possible, clipped phrases when not, his voice when he spoke the sandpapery rasp of one unaccustomed to frequent speech. Now he was sitting on a dining-room chair he had positioned at the group's perimeter, between the dining room and the living room, a long-necked bottle of beer cradled in his hands. We shifted in our respective seats to face him, and he repeated, "I do; I have a mummy story...."

Langan accumulates weight and atmosphere with calm assurance in this first section of "On Skua Island." My thought, as a reader, was: I hope it goes on like this forever.

The story Nicholas recounts takes place twenty-five years ago. While teaching at a Scottish university, he is recruited to join a military intelligence mission to Skua. They entice him with photos:

....A couple of the pictures were clear and close enough for me to have a good look at some of the runes, and when I did my heart started to knock in my chest. I had not seen runes like these before: there were certain family resemblances to runes I knew from parts of Eastern Norway, enough for me to be able to read a couple of words and phrases here and there, but there were also striking variations, and more than a few characters that were completely new, unprecedented. You may be surprised to hear that not once did I doubt these pictures' authenticity, but that was the case. I looked at Green and asked him where this was.

"So you're interested?" he asked. I said I was, and he told me that the island in these photographs was located north-northwest of the Shetlands, an hour and a half's boat ride from the nearest human habitation. The place was called Skua Island, and if I thought that artifact of any archaeological significance, he and his employers—his term—were prepared to send me there to study it within two weeks, as soon as school let out for Christmas holiday....

The team sets up a base camp. Nicholas and his teaching assistance begin excavating. Initial digging uncovers a sword. And below the sword, the mummified remains of a woman.

At night, Nicholas works on translating runes inscribed on the standing stone:

....The translation was no less difficult, but I began to find the rhythm of it, so that even though large patches of it remained unclear, the broad outlines were beginning to swim into view. During this terrible plague, the peoples of the islands had sought high and low, near and far, for relief and found none. There was a considerable list of all the important people who had gone to their graves with the thing, denied the glory of a warrior's death in battle through the machinations of the one who had unleashed it. At last, the leaders of—I thought it was the Shetlands, but it could have been the Orkneys—had decided to seek the aid of a wizard whose name I couldn't quite fix; the characters appeared to be Greek but weren't yielding any intelligible sound; who lived in the Faroe Islands and who was something of a dubious character, having dealings with all sorts of creatures—human, divine, and in-between—whom it was best to give a wide berth. Driven by their desperation, the leaders dispatched an envoy imploring his aid. Twice he refused them, but on the third request his heart softened and he agreed to assist them. He journeyed to the islands on a boat that did not touch the water, or that moved as swiftly as a bird across the water, and when he arrived he wasted no time: disclosing the supernatural origin of the plague, he told the leaders that strong measures would be needed to defeat it. He, the wizard, could summon all the sickness to himself, but he could not purge it from the earth. In order for that to be accomplished, he would require a vessel, by which, as the leaders quickly saw, he meant a human being.

....I tried to decode more about the island leaders' response to the wizard's demand for a human being to serve as vessel to contain the plague. It appeared they had consented to his request with minimal debate: one man, Gunnar, a landowner of some repute, had refused to have anything to do with such dealings, but that same night the plague fell on him and by morning he was dead; his brains, the history detailed, burst and ran out his ears. After Gunnar, no one else contested the leaders' decision, and Frigga, Gunnar's eldest daughter, was selected by the leaders for the wizard's use. Elaborate preparations were made, several lengthy prayers were addressed to various gods—Odin, Loki, and Hel, goddess of death, among them—and then the wizard called all of the plague to himself, from all the islands he summoned it. It came as, or as if, a cloud of insects so vast it filled the sky, blotting out the sun. Men and women covered their heads in fear; an old woman fell dead from terror of it. The wizard commanded the plague into Frigga, who was lying bound at his feet. At first, it did not obey, nor did it heed the wizard's second command, but on his third attempt his power proved greater and the plague descended into Frigga, streaming into her mouth, her nose, her ears, the huge black cloud lodging itself within her, until the sky was once again clear, the sun shining.

This, however, was not the end. Frigga remained alive; she had become as fierce as an animal, straining against her bonds, gnashing her teeth and growling at the wizard and at the islands' leaders, threatening bloody vengeance. Nonplussed, the wizard had her rowed to the island of the—to Skua Island, where she was put ashore, her feet loosed but her hands still bound. The island was full of the skuas; there to nest, I supposed; and when Frigga, or what had been Frigga, set foot among them, they flew at her fiercely, attacking her unprotected face and eyes with no mercy. Her screams were terrible, heard by all the peoples of all the islands. At last, the birds left her with no face and no eyes, which the wizard said was necessary so that she should go unrecognized among the dead, so that she should be unable to find her way out of the place to which he was going to dispatch her. Half a dozen strong men seized her, for even so injured she was fearfully powerful, and bore her up to the summit of one of the island's hills, where the wizard once more bound her feet and slew her by cutting her throat. The blood that spilled out was black, and one of the men it splashed died on the spot. When all the blood had left her, the wizard ordered her body buried at the summit of the opposite hill, and a stone placed over it as a reminder to all the people of all the islands of what he, (once more that name I couldn't decipher), had done for them, and as a warning not to disturb this spot, for now that the girl's body had been used as a vessel for returning (that symbol, the broken circle)'s evil to him, it would be a simple matter for him to return Frigga to her body full of his power, and if he did, she would be awful. He, the wizard, would place a sword between the stone and the girl that would keep her in her place, and he would write the warning on the stone himself, so that all could read it. Woe be to he who disturbed the sword: not only would the wrath of the one who had sent the plague fall on him, but the wrath of the wizard as well, and he would lose to the reborn girl that which she herself had lost, by which I assumed was meant his face.

....Despite the hour, I was exhilarated: in a matter of days, I had rendered into reasonably intelligible English a text written in a language whose idiosyncrasies would have cost many another scholar weeks if not months of effort to overcome. Yes, there was a curse, a pair of curses, threatened against whoever disturbed the site, but such curses were commonplace; indeed, I would have been more surprised had there been no curse, no warning of dire consequences. Melodramatic films aside, when all was said and done, King Tut's curse had been nothing more than a self-fulfilling prophecy. If I was worried about anything, it was the team of Soviet commandos creeping ever closer to us, knives clenched between their teeth, waiting for the precise moment to take revenge on us for whatever operations Collins and his men had been performing. The text on the column I judged an elaborately coded narrative, possibly intended to justify an actual event, the killing of the girl we had discovered, through recourse to supernatural explanations....

This academic work of translation coincides with the killing of several members of the team. Killed in gratuitous acts of violence: skilled warfighters with heads wrenched around backward.

Nicholas sums up:

....there is no culture that is innocent. In most cases, you don't have to dig particularly long or hard to unearth similar events. We are never as far from such things as we would like to think.

Only then does the climax begin:

....The camp was quiet as we sighted it, and as we drew nearer, I saw why: everyone was dead, Collins, Ryan, Joseph, the two others. Ryan was collapsed on a yellow raft, and I could not understand what was wrong with his body until I realized that his head was turned around backwards, his eye sockets empty and bloody, blood trailing from his nose, his open mouth. Collins was on the ground next to him, face down in a wide pool of blood still spreading from where his left arm had been torn from his body and tossed aside, where it lay with a pistol still clenched in its hand. I did my best not to look directly at either of them, because I was afraid that if I did I would join Bruce, who was sobbing behind me. The remaining three men lay with one of the other rafts: a glance that lasted too long showed me another of them with his neck broken, one, I think it was Joseph, with both his arms torn off, the third with a gaping red hole punched into his chest. All their eyes appeared to have been gouged out. There was blood everywhere, flecks, streaks, puddles of red splashed across the scene. From where we were standing on the hill, I could see over the rise beyond the camp to the bay and sea, both of which were empty.

"What happened?" Bruce said. "What happened to them?"

I told him I didn't know and I didn't: no team of Soviet commandos, however brutal, however ruthless, would have done this. Overhead, a small flock of skuas, a half-dozen or so, circled, crying. This, this was gratuitous, this was—I didn't know how to describe it to myself; it was outside my vocabulary.

As was what I saw next....

"On Skua Island" is the finest Scottish adventure story I have read since John Buchan. His Richard Hannay of Island of Sheep and Edward Leithen of John Macnab would be perfectly at home in this climate and with this level of supernatural action.

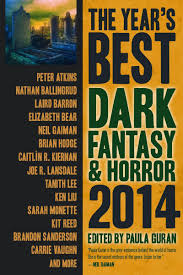

Available in:

Jay