Pity the monsters!

Pity the monsters!

Perhaps, one always took the wrong side –

Ah, to have known, to have loved

too many David and Judiths!

My heart bleeds for the monster.

I have seen the Gorgon.

The erotic terror....

"Florence" by Robert Lowell

Robert Bloch's novels and stories about the mentally unhinged and marginalized offer vivid humor, exalted wordplay, and bitter heartbreak for readers.

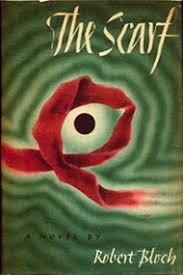

I'll place my bet now without hesitation: The Scarf by Robert Bloch is not only superior to Psycho, it is equal to The Talented Mr. Ripley and The Killer Inside Me.

That's a bold statement. But The Scarf is a bold, desolating, sleekly economical novel. Its characters are perfectly observed. Sentiment has no place in these pages. Self-pity is employed only to highlight the cloud castles of a pathologically unreliable narrator. Bloch's moral strength is that he invariably pities and seeks to understand his monsters; their sane friends, lovers, and antagonists appear as threats and warning alerts of bad weather to come.

Daniel Morley has been on the bum for ten years when we meet him. He tells us about launching himself as a writer, but intercuts those chapters with excerpts from what he calls his "Black Notebook," in which his past is reviewed.

Bloch's handling of this material has the power of primary tragedy:

....Memories, like the time you were five years old and wet the bed, and your mother laughed at you. She made fun of you in front of the whole family while you ate Sunday dinner. You couldn't stand the snickering, and the way she described what you'd done. You ran from the table and vomited everything up. Only you couldn't vomit up one thing—the sudden hate, curling away in the pit of your stomach.

Your own mother! You wondered what she meant when she whined and whispered to you because you happened to pass the bathroom when your sister Geraldine was in the tub.

"What did you look at her for?" she asked. "Only nasty little boys look at little girls."

Then, memories of the day she caught you, behind the woodpile back of the house, playing Doctor—what the psychologists sweetly call "exploratory sex play"—with a little neighbor girl of your own age, which was nine. Your mother saw you, said you were filthy, ridiculed you, made your father switch you good and hard. She sold you thoroughly on the idea that sex was vile and shameful. You were a vile, filthy boy. You took it, dumbly, the way kids must, and that night at dinner she brought it up again, rubbing it in.

Later, hours later, you tossed on your bed, unable to sleep, because she'd tied your hands to the bedposts as punishment—to keep you, in her words, from polluting yourself—and because you didn't know exactly what she meant by vile and filthy. What was filthy? That meant dirty, didn't it? But the little girl had been clean and so had you.

Finally, overcome with thirst, you had slipped the bonds of ripped red flannel holding your wrists and had sneaked down the hall to the bathroom to get a drink of water. It was hot summer—you remember hearing the locusts singing and smelling the wild honeysuckle. Your parents' door was open and as you passed you saw and heard what they were doing, their nakedness and the panting. You remember that you fled back to your room, slipped back into the flannel bonds.

You remember the numb turmoil of your feelings; you didn't think; your conscious mind refused the whole thing. But then, she had called you filthy and she was filthy too!

You hated your mother from then on, although you didn't know then that it was hate. You had rejected her completely and she, sensing she'd lost a victory, sensing your coldness and loathing, took it out on you in constant and bitter nagging....

Morley keeps meeting women, and as with many writers he turns them into characters in stories. When the stories are done, he moves on. With the help of his maroon scarf.

.... You wonder why it is they can all enjoy themselves and you aren't having any fun.

Or are you thinking: yes, these are people, a pretty ordinary crowd of people at that. They pay taxes, they vote, they make the laws, they choose the popular songs and the books and the pictures, they tell us all how to live and how to work and what to think and worship. Yes, and if they were on your jury, your life would be in their hands.

Is that the way you figure it? Do you wish, as you watch them dancing, that you could walk right up to the bandstand and take out a sub-machine gun and let 'em have it, just mow 'em down; the whole cruel, greedy, moronic, dirty lot of them?

Maybe I'm wrong.

Maybe most people don't have those thoughts, those feelings, those desires.

Maybe it's just people like me.

Maybe they'd be afraid of me if they knew what went on inside. I must never let them find out. Write it all down, but don't tell anybody.

But I'd like to tell them. I'd like to let them know how I feel. How it feels. The whole works. I'd like to give them all a little personal demonstration.

Dan falls in with the New York cocktail literati. His first novel is a big success, and his second is sold to the movies. A woman named Constance puts him in her crosshairs.

"Constance is a nympholept."

"You mean, oversexed?"

"More than that. Nympholepsy is much more than a mere physical condition; a glandular maladjustment may, however, be a contributory cause. In the old days they called the condition 'nymphomania.' It's probably a better term. Because a woman so afflicted is a maniac."

I put out my cigarette. My mouth was too dry.

"Insatiable sexual appetite is a terrible thing, Dan." Somehow Ruppert didn't sound like a college boy any more. "It rarely appears in its pure form, however. Often it is accompanied by delusions, hallucinations. You've surely heard the old legends about the incubus: the carnal night demon who visits women in their dreams. Witches had such delusions—and nuns, too. And it's easy to spot a psychotic when the disorder is characterized by fantasies. When there are no fantasies, it's difficult. Very difficult." He shook his head.

"When a young girl has a so-called 'nervous breakdown' in school, her fellow-pupils and instructors, her own father, are likely to shrug it off. There's no babbling of dreams and visions, no delusions of persecution, disorders of perception, no outward hysteria. The hysteria is all inside.

"When the young girl visits a psychoanalyst for treatment and develops a violent fixation on him, the world calls it love. They don't hear the panting confessions, the moans, the sobs, the threats of suicide.

"The analyst doesn't tell them, either, if he knows that the threats are genuine. If he feels that perhaps, in time, he can cure the disorder. Particularly, if he has the misfortune to fall in love with her. Actually it was pity; believe me in that, Dan, although I pity her no longer....

Dr. Ruppert, a friend from cocktail land, is one of Bloch's sophisticated psychiatrists, clever and modern, smart and observant.

"But there's one thing I'm curious about, Dan. With all your perception of the feminine mind, why do you hate women?"

I didn't have any answers ready for that one.

He leaned closer. "You don't happen to be a homosexual, do you?"

Guys get hit for saying things like that, but somehow he asked the question honestly, the way a doctor would. "No. Quite the contrary."

"But you do hate women."

"How do you figure that?"

"I don't figure. It's there, in the book. More than detachment, cynicism, objectivity—I can sense pure hatred in your descriptions and the attitudes behind them. Actually, you don't describe. You dissect. Sadistically."

"Wait a minute, now, I'm not Jack the Ripper."

"Are you sure?"

Once again he had me off balance.

"Are you positive that you aren't writing as a sort of safety valve, to keep you from taking more direct action?"

"Are you positive you aren't trying to psychoanalyze me?"

Ruppert sat back and shrugged. "Maybe so. I think you'd make a very interesting patient, Dan."

In the end, Daniel Morley cannot ask for help because he spends every waking minute try to keep all the plates in the air: maintaining the appearance of sanity leaves no room for anything else. Like James Ellroy's protagonist in Killer on the Road, killing and moving on is normality.

Jay

15 February

No comments:

Post a Comment