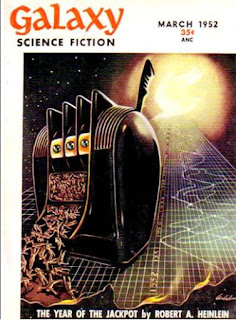

"Year of the Jackpot" is a 1952 short story by Robert A.

Heinlein. It first appeared in Galaxy

magazine that year. It can be found in the collection The

Menace from Earth.

It's an end-of-the-world science fiction story, for which I have a

weakness.

It's also a math fiction story, or more precisely statistics.

I first read it in 1999, after finding several references to it in the Encyclopedia

of Science Fiction, which I read cover to cover that summer while

unemployed.

Heinlein has a slick style that is easy to take; it's the kind of glib

voice one would expect to hear at a cocktail party full of cosmopolitan

sophisticates in the fifties.

It is easier to enjoy Heinlein if you know nothing about him or his

politics.* "The Year of the

Jackpot" is a breath of fresh air compared to his later, thicker, weaker

novels that indulged themselves in incestuous solipsism.

A good discussion of Heinlein can be found in Thomas M. Disch’s fine

book The

Dreams Our Stuff is Made Of: How Science Fiction Conquered the World. Indeed, reading the Disch book prompted me to

seek out Heinlein in the first place.

***

The Year of the Jackpot

by Robert A. Heinlein

At first Potiphar

Breen did not notice the girl who was undressing.

She was standing

at a bus stop only ten feet away. He was indoors but that would not have kept

him from noticing; he was seated in a drugstore booth adjacent to the bus stop;

there was nothing between Potiphar and the young lady but plate glass and an

occasional pedestrian.

Nevertheless he

did not look up when she began to peel. Propped up in front of him was a Los

Angeles Times; beside it, still unopened, were the Herald-Express and the Daily

News. He was scanning the newspaper carefully but the headline stories got only

a passing glance. He noted the maximum and minimum temperatures in Brownsville,

Texas and entered them in a neat black notebook; he did the same with the

closing prices of three blue chips and two dogs on the New York Exchange, as

well as the total number of shares. He then began a rapid sifting of minor news

stories, from time to time entering briefs of them in his little book; the

items he recorded seemed randomly unrelated--among them a publicity release in

which Miss National Cottage Cheese Week announced that she intended to marry

and have twelve children by a man who could prove that he had been a life-long

vegetarian, a circumstantial but wildly unlikely flying saucer report, and a

call for prayers for rain throughout Southern California.

Potiphar had just

written down the names and addresses of three residents of Watts, California

who had been miraculously healed at a tent meeting of the God-is-AII First

Truth Brethren by the Reverend Dickie Bottomley, the eight-year-old evangelist,

and was preparing to tackle the Herald-Express, when he glanced over his

reading glasses and saw the amateur ecdysiast on the street comer outside. He

stood up, placed his glasses in their case, folded the newspapers and put them

carefully in his right coat pocket, counted out the exact amount of his check

and added twenty-five cents. He then took his raincoat from a hook, placed it

over his arm, and went outside.

By now the girl

was practically down to the buff. It seemed to Potiphar Breen that she had

quite a lot of buff. Nevertheless she had not pulled much of a house. The

corner newsboy had stopped hawking his disasters and was grinning at her, and a

mixed pair of transvestites who were apparently waiting for the bus had their

eyes on her. None of the passers-by stopped. They glanced at her, then with the

self-conscious indifference to the unusual of the true Southern Californian,

they went on their various ways. The transvestites were frankly staring. The

male member of the team wore a frilly feminine blouse but his skirt was a

conservative Scottish kilt--his female companion wore a business suit and

Homburg hat; she stared with lively interest.

As Breen

approached the girl hung a scrap of nylon on the bus stop bench, then reached

for her shoes. A police officer, looking hot and unhappy, crossed with the

lights and came up to them. "Okay," he said in a tired voice,

"that'll be all, lady. Get them duds back on and clear out of here."

The female

transvestite took a cigar out of her mouth. "Just," she said,

"what business is it of yours, officer?" The cop turned to her.

"Keep out of this!" He ran his eyes over her get up, that of her

companion. "I ought to run both of you in, too."

The transvestite

raised her eyebrows. "Arrest us for being clothed, arrest her for not

being. I think I'm going to like this." She turned to the girl, who was

standing still and saying nothing, as if she were puzzled by what was going on.

"I'm a lawyer, dear." She pulled a card from her vest pocket.

"If this uniformed Neanderthal persists in annoying you, I'll be delighted

to handle him."

The man in the

kilt said, "Grace! Please!"

She shook him off.

"Quiet, Norman-this is our business." She went on to the policeman,

"Well? Call the wagon. In the meantime my client will answer no

questions."

The official

looked unhappy enough to cry and his face was getting dangerously red. Breen

quietly stepped forward and slipped his raincoat around the shoulders of the

girl. She looked startled and spoke for the first time. "Uh-thanks."

She pulled the coat about her, cape fashion.

The female attorney glanced at Breen then back to the cop. "Well,

officer? Ready to arrest us?"

He shoved his face

close to hers. "I ain't going to give you the satisfaction!" He

sighed and added, "Thanks, Mr. Breen-you know this lady?"

"I'll take

care of her. You can forget it, Kawonski."

"I sure hope

so. If she's with you, I'll do just that. But get her out of here, Mr.

Breen-please!"

The lawyer

interrupted. "Just a moment-you're interfering with my client."

Kawonski said,

"Shut up, you! You heard Mr. Breen-she's with him. Right, Mr. Breen?"

"Well yes.

I'm a friend. I'll take care of her."

The transvestite

said suspiciously, "I didn't hear her say that."

Her companion

said, "Grace-please! There's our bus."

"And I didn't

hear her say she was your client," the cop retorted. "You look like

a-" His words were drowned out by the bus's brakes, "-and besides

that, if you don't climb on that bus and get off my territory, I'll . . . I'll

. . ."

"You'll

what?"

"Grace! We'll

miss our bus."

"Just a

moment, Norman. Dear, is this man really a friend of yours? Are you with

him?"

The girl looked

uncertainly at Breen, then said in a low voice, "Uh, yes. That's

right."

"Well . .

." The lawyer's companion pulled at her arm. She shoved her card into

Breen's hand and got on the bus; it pulled away.

Breen pocketed the

card. Kawonski wiped his forehead.

"Why did you

do it, lady?" he said peevishly.

The girl looked

puzzled. "I . . . I don't know."

"You hear

that, Mr. Breen? That's what they all say. And if you pull 'em in, there's six

more the next day. The Chief said-" He sighed. "The Chief said well,

if I had arrested her like that female shyster wanted me to. I'd be out at a

hundred and ninety-sixth and Ploughed Ground tomorrow morning, thinking about

retirement. So get her out of here, will you?"

The girl said,

"But-"

"No 'buts,'

lady. Just be glad a real gentleman like Mr. Breen is willing to help

you." He gathered up her clothes, handed them to her. When she reached for

them she again exposed an uncustomary amount of skin; Kawonski hastily gave

them to Breen instead, who crowded them into his coat pockets.

She let Breen lead

her to where his car was parked, got in and tucked the raincoat around her so

that she was rather more dressed than a girl usually is. She looked at him. She

saw a medium-sized and undistinguished man who was slipping down the wrong side

of thirty-five and looked older. His eyes had that mild and slightly naked look

of the habitual spectacles wearer who is not at the moment with glasses; his

hair was gray at the temples and thin on top. His herringbone suit, black

shoes, white shirt, and neat tie smacked more of the East than of California.

He saw a face

which he classified as "pretty" and "wholesome" rather than

"beautiful" and "glamorous," It was topped by a healthy mop

of light brown hair. He set her age at twenty-five, give or take eighteen

months. He smiled gently, climbed in without speaking and started his car. He

turned up Doheny Drive and east on Sunset. Near La Cienega he slowed down.

"Feeling better?"

"Uh, I guess

so. Mr.-'Breen'?"

"Call me

Potiphar. What's your name? Don't tell me if you don't want to,"

"Me? I'm . .

. I'm Meade Barstow."

"Thank you,

Meade. Where do you want to go? Home?"

"I suppose

so. I-Oh my no! I can't go home like this." She clutched the coat tightly

to her.

"Parents?"

"No. My

landlady. She'd be shocked to death."

"Where,

then?"

She thought.

"Maybe we could stop at a filling station and I could sneak into the

ladies' room."

"Mmm. . .

maybe. See here, Meade, my house is six blocks from here and has a garage

entrance. You could get inside without being seen." He looked at her.

She stared back.

"Potiphar you don't look like a wolf?"

"Oh, but I

am! The worst sort." He whistled and gnashed his teeth. "See? But

Wednesday is my day off from it." She looked at him and dimpled. "Oh,

well! I'd rather wrestle with you than with Mrs. Megeath. Let's go."

He turned up into

the hills. His bachelor diggings were one of the many little frame houses

clinging like fungus to the brown slopes of the Santa Monica Mountains. The

garage was notched into this hill; the house sat on it. He drove in, cut the

ignition, and led her up a teetery inside stairway into the living room.

"In there," he said, pointing. "Help yourself." He pulled

her clothes out of his coat pockets and handed them to her.

She blushed and

took them, disappeared into his bed- room. He heard her turn the key in the

lock. He settled down in his easy chair, took out his notebook, and opened the

Herald-Express.

He was finishing

the Daily News and had added several notes to his collection when she came out.

Her hair was neatly rolled; her face was restored; she had brushed most of the

wrinkles out of her skirt. Her sweater was neither too tight nor deep cut, but

it was pleasantly filled. She reminded him of well water and farm breakfasts.

He took his

raincoat from her, hung it up, and said, "Sit down, Meade."

She said

uncertainly, "I had better go."

"Go if you

must-but I had hoped to talk with you."

"Well-"

She sat down on the edge of his couch and looked around. The room was small but

as neat as his necktie, clean as his collar. The fireplace was swept; the floor

was bare and polished. Books crowded bookshelves in every possible space. One

corner was filled by an elderly flat-top desk; the papers on it were neatly in

order. Near it, on its own stand, was a small electric calculator. To her

right, French windows gave out on a tiny porch over the garage. Beyond it she

could see the sprawling city; a few neon signs were already blinking.

She sat back a

little. "This is a nice room-Potiphar. It looks like you."

"I take that

as a compliment. Thank you." She did not answer; he went on, "Would

you like a drink?"

"Oh, would

I!" She shivered. "I guess I've got the jitters."

He got up.

"Not surprising. What'll it be?"

She took Scotch

and water, no ice; he was a Bourbon-and-ginger-ale man. She had soaked up half

her highball in silence, then put it down, squared her shoulders and said,

"Potiphar?"

"Yes,

Meade?"

"Look-if you

brought me here to make a pass, I wish you'd go ahead and make it. It won't do

you a bit of good, but it makes me nervous to wait for it."

He said nothing

and did not change his expression. She went on uneasily, "Not that I'd

blame you for trying-under the circumstances. And I am grateful. But . . . well

it's just that I don't-"

He came over and

took both her hands. "My dear, I haven't the slightest thought of making a

pass at you. Nor need you feel grateful. I butted in because I was interested

in your case."

"My case? Are

you a doctor? A psychiatrist?"

He shook his head.

"I'm a mathematician. A statistician, to be precise."

"Hub? I don't

get it." "Don't worry about it. But I would like to ask some

questions. May I?"

"Uh, sure,

sure! I owe you that much-and then some."

"You owe me

nothing. Want your drink sweetened?"

She gulped it and

handed him her glass, then followed him out into the kitchen. He did an exact

job of measuring and gave it back. "Now tell me why you took your clothes

off?"

She frowned.

"I don't know. I don't know. I don't know. I guess I just went

crazy." She added round-eyed, "But I don't feel crazy. Could I go off

my rocker and not know it?" "You're not crazy . . . not more so than

the rest of us," he amended. "Tell me, where did you see someone else

do this?"

"Huh? But I

never have."

"Where did

you read about it?"

"But I

haven't. Wait a minute-those people up in Canada. Dooka-somethings."

"Doukhobors.

That's all? No bareskin swimming parties? No strip poker?"

She shook her

head. "No. You may not believe it but I was the kind of a little girl who

undressed under her nightie." She colored and added, "I still

do--unless I remember to tell myself it's silly."

"I believe

it. No news stories?"

"No. Yes,

there was too! About two weeks ago, I think it was. Some girl in a theater, in

the audience, I mean. But I thought it was just publicity. You know the stunts

they pull here."

He shook his head.

"It wasn't. February 3rd, the Grand Theater, Mrs. Alvin Copley. Charges

dismissed."

"Huh? How did

you know?"

"Excuse

me." He went to his desk, dialed the City News Bureau. "Alf? This is

Pot Breen. They still sitting on that story? . . . yes, yes, the Gypsy Rose

file. Any new ones today?" He waited; Meade thought that she could make

out swearing. "Take it easy, Alf-this hot weather can't last forever.

Nine, eh? Well, add another-Santa Monica Boulevard, late this afternoon. No

arrest." He added, "Nope, nobody got her name-a middle-aged woman

with a cast in one eye. I happened to see it . . . who, me? Why would I want to

get mixed up? But it's rounding up into a very, very interesting picture."

He put the phone down.

Meade said,

"Cast in one eye, indeed!"

"Shall I call

him back and give him your name?"

"Oh,

no!"

"Very well.

Now, Meade, we seemed to have located the point of contagion in your case--Mrs.

Copley. What I'd like to know next is how you felt, what you were thinking

about, when you did it?"

She was frowning

intently. "Wait a minute, Potiphar--do I understand that nine other girls

have pulled the stunt I pulled?"

"Oh, no-nine

others today. You are-" He paused briefly. "-the three hundred and

nineteenth case in Los Angeles county since the first of the year. I don't have

figures on the rest of the country, but the suggestion to clamp down on the

stories came from the eastern news services when the papers here put our first

cases on the wire. That proves that it's a problem elsewhere, too."

"You mean

that women all over the country are peeling off their clothes in public? Why,

how shocking!"

He said nothing.

She blushed again and insisted, "Well, it is shocking, even if it was me,

this time."

"No, Meade.

One case is shocking; over three hundred makes it scientifically interesting.

That's why I want to know how it felt. Tell me about it."

"But-All

right, I'll try. I told you I don't know why I did it; I still don't. I-"

"You remember

it?"

"Oh, yes! I

remember getting up off the bench and pulling up my sweater. I remember

unzipping my skirt. I remember thinking I would have to hurry as I could see my

bus stopped two blocks down the street. I remember how good it felt when I

finally, uh-" She paused and looked puzzled. "But I still don't know

why."

"What were

you thinking about just before you stood up?"

"I don't

remember."

"Visualize

the street. What was passing by? Where were your hands? Were your legs crossed

or uncrossed? Was there anybody near you? What were you thinking about?"

"Uh . . . nobody

was on the bench with me. I had my hands in my lap. Those characters in the

mixed-up clothes were standing near by, but I wasn't paying attention. I wasn't

thinking much except that my feet hurt and I wanted to get home-and how

unbearably hot and sultry it was. Then--" Her eyes became distant,

"--suddenly I knew what I had to do and it was very urgent that I do it.

So I stood up and I . . . and I--" Her voice became shrill.

"Take it

easy!" he said. "Don't do it again."

"Huh? Why,

Mr. Breen! I wouldn't do anything like that."

"Of course

not. Then what?"

"Why, you put

your raincoat around me and you know the rest." She faced him. "Say,

Potiphar, what were you doing with a raincoat? It hasn't rained in weeks--this

is the driest, hottest rainy season in years."

"In

sixty-eight years, to be exact."

"Huh?"

"I carry a

raincoat anyhow. Uh, just a notion of mine, but I feel that when it does rain,

it's going to rain awfully hard." He added, "Forty days and forty

nights, maybe."

She decided that

he was being humorous and laughed.

He went on,

"Can you remember how you got the idea?"

She swirled her

glass and thought. "I simply don't know."

He nodded.

"That's what I expected."

"I don't

understand you--unless you think I'm crazy. Do you?"

"No. I think

you had to do it and could not help it and don't know why and can't know

why."

"But you

know." She said it accusingly.

"Maybe. At

least I have some figures. Ever take any interest in statistics, Meade?"

She shook her

head. "Figures confuse me. Never mind statistics--I want to know why I did

what I did!"

He looked at her

very soberly. "I think we're lemmings, Meade."

She looked

puzzled, then horrified. "You mean those little furry mouselike creatures?

The ones that--"

"Yes. The

ones that periodically make a death migration, until millions, hundreds of

millions of them drown themselves in the sea. Ask a lemming why he does it. If

you could get him to slow up his rush toward death, even money says he would

rationalize his answer as well as any college graduate. But he does it because

he has to--and so do we."

"That's a

horrid idea, Potiphar."

"Maybe. Come

here, Meade. I'll show you figures that confuse me, too." He went to his

desk and opened a drawer, took out a packet of cards. "Here's one. Two

weeks ago a man sues an entire state legislature for alienation of his wife's

affection--and the judge lets the suit be tried. Or this one--a patent

application for a device to lay the globe over on its side and warm up the

arctic regions. Patent denied, but the inventor took in over three hundred

thousand dollars in down payments on South Pole real estate before the postal

authorities stepped in. Now he's fighting the case and it looks as if he might

win. And here--prominent bishop proposes applied courses in the so-called facts

of life in high schools." He put the card away hastily. "Here's a

dilly: a bill introduced in the Alabama lower house to repeal the laws of

atomic energy--not the present statutes, but the natural laws concerning nuclear

physics; the wording makes that plain." He shrugged. "How silly can

you get?"

"They're

crazy."

"No, Meade.

One such is crazy; a lot of them is a lemming death march. No, don't

object--I've plotted them on a curve. The last time we had anything like this

was the so-called Era of Wonderful Nonsense. But this one is much worse."

He delved into a lower drawer, hauled out a graph. "The amplitude is more

than twice as great and we haven't reached peak. What the peak will be I don't

dare guess three separate rhythms, reinforcing."

She peered at the

curves. "You mean that the laddy with the artic real estate deal is

somewhere on this line?"

"He adds to

it. And back here on the last crest are the flag- pole sitters and the goldfish

swallowers and the Ponzi hoax and the marathon dancers and the man who pushed a

peanut up Pikes Peak with his nose. You're on the new crest-or you will be when

I add you in."

She made a face.

"I don't like it."

"Neither do

I. But it's as clear as a bank statement. This year the human race is letting

down its hair, flipping its lip with a finger, and saying, 'Wubba, wubba,

wubba."'

She shivered.

"Do you suppose I could have another drink? Then I'll go."

"I have a

better idea. I owe you a dinner for answering questions. Pick a place and we'll

have a cocktail before."

She chewed her

lip. "You don't owe me anything. And I don't feel up to facing a

restaurant crowd. I might . . . I might-"

"No, you

wouldn't," he said sharply. "It doesn't hit twice."

"You're sure?

Anyhow, I don't want to face a crowd." She glanced at his kitchen door.

"Have you anything to eat in there? I can cook."

"Urn,

breakfast things. And there's a pound of ground round in the freezer

compartment and some rolls. I sometimes make hamburgers when I don't want to go

out."

She headed for the

kitchen. "Drunk or sober, fully dressed or-or naked, I can cook. You'll see."

He did see.

Open-faced sandwiches with the meat married to toasted buns and the flavor

garnished rather than suppressed by scraped Bermuda onion and thin-sliced dill,

a salad made from things she had scrounged out of his refrigerator, potatoes

crisp but not vulcanized. They ate it on the tiny balcony, sopping it down with

cold beer.

He sighed and

wiped his mouth. "Yes, Meade, you can cook."

'"Some day

I'll arrive with proper materials and pay you back. Then I'll prove it."

"You've

already proved it. Nevertheless I accept. But I tell you three times, you owe

me nothing."

"No? If you

hadn't been a Boy Scout, I'd be in jail."

Breen shook his

head. "The police have orders to keep it quiet at all costs-to keep it

from growing. You saw that. And, my dear, you weren't a person to me at the

time. I didn't even see your face; I-"

"You saw

plenty else!"

"Truthfully,

I didn't look. You were just a-a statistic."

She toyed with her

knife and said slowly, "I'm not sure, but I think I've just been insulted.

In all the twenty-five years that I've fought men off, more or less

successfully, I've been called a lot of names-but a 'statistic'-why I ought to

take your slide rule and beat you to death with it."

"My dear

young lady-"

"I'm not a

lady, that's for sure. But I'm not a statistic."

"My dear

Meade, then. I wanted to tell you, before you did anything hasty, that in

college I wrestled varsity middleweight."

She grinned and

dimpled. "That's more the talk a girl likes to hear. I was beginning to be

afraid you had been assembled in an adding machine factory. Potty, you're

rather a dear."

"If that is a

diminutive of my given name, I like it. But if it refers to my waist line, I

resent it."

She reached across

and patted his stomach. "I like your waist line; lean and hungry men are

difficult. If I were cooking for you regularly, I'd really pad it."

"Is that a

proposal?"

"Let it lie,

let it lie-Potty, do you really think the whole country is losing its

buttons?"

He sobered at

once. "It's worse than that."

"Huh?"

"Come inside.

I'll show you." They gathered up dishes and dumped them in the sink, Breen

talking all the while. "As a kid I was fascinated by numbers. Numbers are

pretty things and they combine in such interesting configurations. I took my

degree in math, of course, and got a job as a junior actuary with Midwestern

Mutual-the insurance outfit. That was fun-no way on earth to tell when a

particular man is going to die, but an absolute certainty that so many men of a

certain age group would die before a certain date. The curves were so

lovely-and they always worked out. Always. You didn't have to know why; you

could predict with dead certainty and never know why. The equations worked; the

curves were right.

"I was

interested in astronomy too; it was the one science where individual figures

worked out neatly, completely, and accurately, down to the last decimal point

the instruments were good for. Compared with astronomy the other sciences were

mere carpentry and kitchen chemistry.

"I found

there were nooks and crannies in astronomy where individual numbers won't do,

where you have to go over to statistics, and I became even more interested. I

joined the Variable Star Association and I might have gone into astronomy

professionally, instead of what I'm in now-business consultation-if I hadn't

gotten interested in something else."

'"Business

consultation'?" repeated Meade. "Income tax work?"

"Oh,

no-that's too elementary. I'm the numbers boy for a firm of industrial

engineers. I can tell a rancher exactly how many of his Hereford bull calves

will be sterile. Or I tell a motion picture producer how much rain insurance to

carry on location. Or maybe how big a company in a particular line must be to

carry its own risk in industrial accidents. And I'm right, I'm always

right."

"Wait a

minute. Seems to me a big company would have to have insurance."

"Contrariwise.

A really big corporation begins to resemble a statistical universe."

"Huh?"

"Never mind.

I got interested in something else-cycles. Cycles are everything, Meade. And

everywhere. The tides. The seasons. Wars. Love. Everybody knows that in the

spring the young man's fancy lightly turns to what the girls never stopped

thinking about, but did you know that it runs in an eighteen-year-plus cycle as

well? And that a girl born at the wrong swing of the curve doesn't stand nearly

as good a chance as her older or younger sister?"

"What? Is

that why I'm a doddering old maid?"

"You're twenty-five?"

He pondered. "Maybe-but your chances are picking up again; the curve is

swinging up. Anyhow, remember you are just one statistic; the curve applies to

the group. Some girls get married every year anyhow."

"Don't call

me a statistic."

"Sorry. And

marriages match up with acreage planted to wheat, with wheat cresting ahead.

You could almost say that planting wheat makes people get married."

"Sounds

silly."

"It is silly.

The whole notion of cause-and-effect is probably superstition. But the same cycle

shows a peak in house building right after a peak in marriages, every

time."

"Now that

makes sense."

"Does it? How

many newlyweds do you know who can afford to build a house? You might as well

blame it on wheat acreage. We don't know why; it just is."

"Sun spots,

maybe?"

"You can

correlate sun spots with stock prices, or Columbia River salmon, or women's

skirts. And you are just as much justified in blaming short skirts for sun

spots as you are in blaming sun spots for salmon. We don't know. But the curves

go on just the same."

"But there

has to be some reason behind it."

"Does there?

That's mere assumption. A fact has no 'why.' There it stands, self

demonstrating. Why did you take your clothes off today?"

She frowned.

"That's not fair."

"Maybe not.

But I want to show you why I'm worried."

He went into the

bedroom, came out with a large roll of tracing paper. "We'll spread it on

the floor. Here they are, all of them. The 54-year cycle-see the Civil War

there? See how it matches in? The 18 & 1/3 year cycle, the 9-plus cycle,

the 41-month shorty, the three rhythms of sunspots-everything, all combined in

one grand chart. Mississippi River floods, fur catches in Canada, stock market

prices, marriages, epidemics, freight-car loadings, bank clearings, locust

plagues, divorces, tree growth, wars, rainfall, earth magnetism, building

construction patents applied for, murders-you name it; I've got it there."

She stared at the

bewildering array of wavy lines. "But, Potty, what does it mean?"

"It means

that these things all happen, in regular rhythm, whether we like. it or not. It

means that when skirts are due to go up, all the stylists in Paris can't make

'em go down. It means that when prices are going down, all the controls and

supports and government planning can't make 'em go up." He pointed to a

curve. "Take a look at the grocery ads. Then turn to the financial page

and read how the Big Brains try to double-talk their way out of it. It means

that when an epidemic is due, it happens, despite all the public health

efforts. It means we're lemmings."

She pulled her

lip. "I don't like it. 1 am the master of my fate,' and so forth. I've got

free will, Potty. I know I have-I can feel it."

"I imagine

every little neutron in an atom bomb feels the same way. He can go spung! or he

can sit still, just as he pleases. But statistical mechanics work out anyhow.

And the bomb goes off-which is what I'm leading up to. See anything odd there,

Meade?"

She studied the

chart, trying not to let the curving lines confuse her. "They sort of

bunch up over at the right end."

"You're dern

tootin' they do! See that dotted vertical line? That's right now-and things are

bad enough. But take a look at that solid vertical; that's about six months

from now and that's when we get it. Look at the cycles-the long ones, the short

ones, all of them. Every single last one of them reaches either a trough or a

crest exactly on-or almost on-that line."

"That's

bad?"

"What do you

think? Three of the big ones troughed in 1929 and the depression almost ruined

us . . . even with the big 54-year cycle supporting things. Now we've got the

big one troughing-and the few crests are not things that help. I mean to say,

tent caterpillars and influenza don't do us any good, Meade, if statistics mean

anything, this tired old planet hasn't seen a jackpot like this since Eve went

into the apple business. I'm scared."

She searched his

face. "Potty-you're not simply having fun with me? You know I can't check

up on you."

"I wish to

heaven I were. No, Meade, I can't fool about numbers; I wouldn't know how. This

is it. The Year of the Jackpot."

She was very

silent as he drove her home. As they approached West Los Angeles, she said,

"Potty?"

"Yes,

Meade?"

"What do we

do about it?"

"What do you

do about a hurricane? You pull in your ears. What can you do about an atom

bomb? You try to out-guess it, not be there when it goes off. What else can you

do?"

"Oh."

She was silent for a few moments, then added, "Potty? Will you tell me

which way to jump?"

"Hub? Oh,

sure! If I can figure it out."

He took her to her

door, turned to go. She said, "Potty!"

He faced her.

"Yes, Meade?"

She grabbed his

head, shook it-then kissed him fiercely on the mouth. "There-is that just

a statistic?"

"Uh,

no."

"It had

better not be," she said dangerously. "Potty, I think I'm going to

have to change your curve."

II

"RUSSIANS

REJECT UN NOTE"

"MISSOURI

FLOOD DAMAGE EXCEEDS 1951 RECORD"

"MISSISSIPPI

MESSIAH DEFIES COURT"

"NUDIST

CONVENTION STORMS BAILEY'S BEACH"

"BRITISH-IRAN

TALKS STILL DEAD-LOCKED"

"FASTER-THAN-LIGHT

WEAPON PROMISED"

"TYPHOON

DOUBLING BACK ON MANILA"

"MARRIAGE

SOLEMNIZED ON FLOOR OF HUDSON-New York, 13 July, In a specially-constructed

diving suit built for two, Merydith Smithe, cafe society headline girl, and

Prince Augie Schleswieg of New York and the Riviera were united today by Bishop

Dalton in a service televised with the aid of the Navy's ultra-new-"

As the Year of the

Jackpot progressed Breen took melancholy pleasure in adding to the data which

proved that the curve was sagging as predicted. The undeclared World War

continued its bloody, blundering way at half a dozen spots around a tortured

globe. Breen did not chart it; the headlines were there for anyone to read. He

concentrated on the odd facts in the other pages of the papers, facts which,

taken singly, meant nothing, but taken together showed a disastrous trend.

He listed stock

market prices, rainfall, wheat futures, but it was the "silly season"

items which fascinated him. To be sure, some humans were always doing silly

things-but at what point had prime damfoolishness become commonplace? When, for

example, had the zombie-like professional models become accepted ideals of

American womanhood? What were the gradations between National Cancer Week and

National Athlete's Foot Week? On what day had the American people finally taken

leave of horse sense?

Take

transvestism-male-and-female dress customs were arbitrary, but they had seemed

to be deeply rooted in the culture. When did the breakdown start? With Marlene

Dietrich's tailored suits? By the late forties there was no "male"

article of clothing that a woman could not wear in public-but when had men

started to slip over the line? Should he count the psychological cripples who

had made the word "drag" a byword in Greenwich Village and Hollywood

long before this outbreak? Or were they "wild shots" not belonging on

the curve? Did it start with some unknown normal man attending a masquerade and

there discovering that skirts actually were more comfortable and practical than

trousers? Or had it started with the resurgence of Scottish nationalism

reflected in the wearing of kilts by many Scottish-Americans?

Ask a lemming to

state his motives! The outcome was in front of him, a news story. Transvestism

by draft-dodgers had at last resulted in a mass arrest in Chicago which was to

have ended in a giant joint trial-only to have the deputy prosecutor show up in

a pinafore and defy the judge to submit to an examination to determine the

judge's true sex. The judge suffered a stroke and died and the trial was

postponed-postponed forever in Breen's opinion; he doubted that this particular

blue law would ever again be enforced.

Or the laws about

indecent exposure, for that matter. The attempt to limit the Gypsy-Rose

syndrome by ignoring it had taken the starch out of enforcement; now here was a

report about the All Souls Community Church of Springfield: the pastor had

reinstituted ceremonial nudity. Probably the first time this thousand years,

Breen thought, aside from some screwball cults in Los Angeles. The reverend

gentleman claimed that the ceremony was identical with the "dance of the

high priestess" in the ancient temple of Kamak.

Could be-but Breen

had private information that the "priestess" had been working the

burlesque & nightclub circuit before her present engagement. In any case

the holy leader was packing them in and had not been arrested. Two weeks later

a hundred and nine churches in thirty- three states offered equivalent

attractions. Breen entered them on his curves.

This queasy oddity

seemed to him to have no relation to the startling rise in the dissident

evangelical cults throughout the country. These churches were sincere, earnest

and poor-but growing, ever since the War. Now they were multiplying like yeast.

It seemed a statistical cinch that the United States was about to become

godstruck again. He correlated it with Transcendentalism and the trek of the

Latter Day Saints-hmm . . . yes, it fitted. And the curve was pushing toward a

crest.

Billions in war

bonds were now falling due; wartime marriages were reflected in the swollen

peak of the Los Angeles school population. The Colorado River was at a record

low and the towers in Lake Mead stood high out of the water. But the Angelenos

committed slow suicide by watering lawns as usual. The Metropolitan Water

District commissioners tried to stop it-it fell between the stools of the

police powers of fifty "sovereign" cities. The taps remained open,

trickling away the life blood of the desert paradise.

The four regular

party conventions-Dixiecrats, Regular Republicans, the other Regular

Republicans, and the Democrats-attracted scant attention, as the Know-Nothings

had not yet met. The fact that the "American Rally," as the

Know-Nothings preferred to be called, claimed not to be a party but an

educational society did not detract from their strength. But what was their

strength? Their beginnings had been so obscure that Breen had had to go back

and dig into the December 1951 files-but he had been approached twice this very

week to join them, right inside his own office, once by his boss, once by the

janitor.

He hadn't been

able to chart the Know-Nothings. They gave him chills in his spine. He kept

column-inches on them, found that their publicity was shrinking while their numbers

were obviously zooming.

Krakatau blew up

on July i8th. It provided the first important transpacific TV-cast; its effect

on sunsets, on solar constant, on mean temperature, and on rainfall would not

be felt until later in the year. The San Andreas fault, its stresses unrelieved

since the Long Beach disaster of 19331 continued to build up imbalance-an

unhealed wound running the full length of the West Coast. Pelee and Etna

erupted; Mauna Loa was still quiet.

Flying saucers

seemed to be landing daily in every state. No one had exhibited one on the

ground-or had the Department of Defense sat on them? Breen was unsatisfied with

the off-the-record reports he had been able to get; the alcoholic content of

some of them had been high. But the sea serpent on Ventura Beach was real; he

had seen it. The troglodyte in Tennessee he was not in a position to verify.

Thirty-one

domestic air crashes the last week in July. . .was it sabotage? Or was it a

sagging curve on a chart? And that neo-polio epidemic that skipped from Seattle

to New York? Time for a big epidemic? Breen's chart said it was. But how about

B.W.? Could a chart know that a Slav biochemist would perfect an efficient

virus-and-vector at the right time? Nonsense!

But the curves, if

they meant anything at all, included "free will"; they averaged in

all the individual "wills" of a statistical universe-and came out as

a smooth function, Every morning three million "free wills" flowed

toward the center of the New York megapolis; every evening they flowed out

again-all by "free will," and on a smooth and predictable curve.

Ask a lemming! Ask

all the lemmings, dead and alive-let them take a vote on it! Breen tossed his

notebook aside and called Meade, "Is this my favorite statistic?"

"Potty! I was

thinking about you."

"Naturally.

This is your night off."

"Yes, but

another reason, too. Potiphar, have you ever taken a look at the Great

Pyramid?"

"I haven't

even been to Niagara Falls. I'm looking for a rich woman, so I can

travel."

"Yes, yes,

I'll let you know when I get my first million, but-"

"That's the

first time you've proposed to me this week."

"Shut up.

Have you ever looked into the prophecies they found inside the pyramid?"

"Huh? Look,

Meade, that's in the same class with astrology-strictly for squirrels. Grow

up."

"Yes, of

course. But Potty, I thought you were interested in anything odd. This is

odd."

"Oh. Sorry.

If it's 'silly season' stuff, let's see it."

"All right.

Am I cooking for you tonight?"

"It's

Wednesday, isn't it?"

"How

soon?"

He glanced at his

watch. "Pick you up in eleven minutes." He felt his whiskers.

"No, twelve and a half."

"I'll be

ready. Mrs. Megeath says that these regular dates mean that you are going to

marry me."

"Pay no

attention to her. She's just a statistic. And I'm a wild datum."

"Oh, well,

I've got two hundred and forty-seven dollars toward that million. 'Bye!"

Meade's prize was

the usual Rosicrucian come-on, elaborately printed, and including a photograph

(retouched, he was sure) of the much disputed line on the corridor wall which

was alleged to prophesy, by its various discontinuities, the entire future.

This one had an unusual time scale but the major events were all marked on

it-the fall of Rome, the Norman Invasion, the Discovery of America, Napoleon, the

World Wars.

What made it

interesting was that it suddenly stopped-now.

"What about

it. Potty?"

"I guess the

stonecutter got tired. Or got fired. Or they got a new head priest with new

ideas." He tucked it into his desk. "Thanks. I'll think about how to

list it." But he got it out again, applied dividers and a magnifying

glass. "It says here," he announced, "that the end comes late in

August-unless that's a fly speck."

"Morning or

afternoon? I have to know how to dress."

"Shoes will

be worn. All God's chilluns got shoes." He put it away.

She was quiet for

a moment, then said, "Potty, isn't it about time to jump?"

"Huh? Girl,

don't let that thing affect you! That's 'silly season' stuff."

"Yes. But

take a look at your chart."

Nevertheless he

took the next afternoon off, spent it in the reference room of the main

library, confirmed his opinion of soothsayers. Nostradamus was pretentiously

silly, Mother Shippey was worse. In any of them you could find what you looked

for.

He did find one

item in Nostradamus that he liked: "The Oriental shall come forth from his

seat . . . he shall pass through the sky, through the waters and the snow, and

he shall strike each one with his weapon."

That sounded like

what the Department of Defense expected the commies to try to do to the Western

Allies. But it was also a description of every invasion that had come out of

the "heartland" in the memory of mankind. Nuts!

When he got home

he found himself taking down his father's Bible and turning to Revelations. He

could not find anything that he could understand but he got fascinated by the

recurring use of precise numbers. Presently he thumbed through the Book at

random; his eye lit on: "Boast not thyself of tomorrow; for thou knowest

not what a day may bring forth." He put the Book away, feeling humbled but

not cheered.

The rains started

the next morning. The Master Plumbers elected Miss Star Morning "Miss

Sanitary Engineering" on the same day that the morticians designated her

as "The Body I would Like Best to Prepare," and her option was

dropped by Fragrant Features. Congress voted $1.37 to compensate Thomas

Jefferson Meeks for losses incurred while an emergency postman for the

Christmas rush of 1936, approved the appointment of five lieutenant generals

and one ambassador and adjourned in eight minutes. The fire extinguishers in a

midwest orphanage turned out to be filled with air. The chancellor of the

leading football institution sponsored a fund to send peace messages and

vitamins to the Politburo. The stock market slumped nineteen points and the

tickers ran two hours late. Wichita, Kansas, remained flooded while Phoenix,

Arizona, cut off drinking water to areas outside city limits. And Potiphar

Breen found that he had left his raincoat at Meade Barstow's rooming house.

He phoned her

landlady, but Mrs. Megeath turned him over to Meade. "What are you doing

home on a Friday?" he demanded.

"The theater

manager laid me off. Now you'll have to marry me."

"You can't

afford me. Meade-seriously, baby, what happened?"

"I was ready

to leave the dump anyway. For the last six weeks the popcorn machine has been

carrying the place. Today I sat through I Was A Teen-Age Beatnik twice. Nothing

to do."

"I'll be

along."

"Eleven

minutes?"

"It's

raining. Twenty-with luck."

It was more nearly

sixty. Santa Monica Boulevard was a navigable stream; Sunset Boulevard was a

subway jam. When he tried to ford the streams leading to Mrs. Megeath's house,

he found that changing tires with the wheel wedged against a storm drain

presented problems.

"Potty! You

look like a drowned rat."

"I'll

live," But presently he found himself wrapped in a blanket robe belonging

to the late Mr. Megeath and sipping hot cocoa while Mrs. Megeath dried his

clothing in the kitchen.

"Meade . . .

I'm 'at liberty,' too."

"Hub? You

quit your job?"

"Not exactly.

Old Man Wiley and I have been having differences of opinion about my answers

for months-too much 'Jackpot factor' in the figures I give him to turn over to

clients. Not that I call it that, but he has felt that I was unduly

pessimistic."

"But you were

right!"

"Since when

has being right endeared a man to his boss? But that wasn't why he fired me;

that was just the excuse. He wants a man willing to back up the Know-Nothing

program with scientific double-talk. And I wouldn't join." He went to the

window. "It's raining harder."

"But they

haven't got any program."

"I know

that."

"Potty, you

should have joined. It doesn't mean anything-I joined three months ago."

"The hell you

did!"

She shrugged.

"You pay your dollar and you turn up for two meetings and they leave you

alone. It kept my job for another three months. What of it?"

"Uh, well-I'm

sorry you did it; that's all. Forget it. Meade, the water is over the curbs out

there."

"You had

better stay here overnight."

"Mmm . . . I

don't like to leave 'Entropy' parked out in this stuff all night. Meade?"

"Yes,

Potty?"

"We're both

out of jobs. How would you like to duck north into the Mojave and find a dry

spot?"

"I'd love it.

But look, Potty-is this a proposal, or just a proposition?"

"Don't pull

that 'either-or' stuff on me. It's just a suggestion for a vacation. Do you

want to take a chaperone?"

"No."

"Then pack a

bag."

"Right away.

But look, Potiphar-pack a bag how? Are you trying to tell me it's time to

jump?"

He faced her, then

looked back at the window. "I don't know," he said slowly, "but

this rain might go on quite a while. Don't take anything you don't have to

have-but don't leave anything behind you can't get along without."

He repossessed his

clothing from Mrs. Megeath while Meade was upstairs, She came down dressed in

slacks and carrying two large bags; under one arm was a battered and rakish

Teddy bear. "This is Winnie."

"Winnie the

Pooh?"

"No, Winnie

Churchill. When I feel bad he promises me 'blood, toil, tears, and sweat'; then

I feel better. You said to bring anything I couldn't do without?" She

looked at him anxiously.

"Right."

He took the bags. Mrs. Megeath had seemed satisfied with his explanation that

they were going to visit his (mythical) aunt in Bakersfield before looking for

jobs; nevertheless she embarrassed him by kissing him good-by and telling him

to "take care of my little girl."

Santa Monica

Boulevard was blocked off from use. While stalled in traffic in Beverly Hills

he fiddled with the car radio, getting squawks and crackling noises, then

finally one station nearby: "-in effect," a harsh, high, staccato

voice was saying, "the Kremlin has given us till sundown to get out of

town. This is your New York Reporter, who thinks that in days like these every

American must personally keep his powder dry. And now for a word from-"

Breen switched it off and glanced at her face. "Don't worry," he

said. "They've been talking that way for years,"

"You think

they are bluffing?"

"I didn't say

that. I said, 'don't worry.' "

But his own

packing, with her help, was clearly on a "Survival Kit" basis-canned

goods, all his warm clothing, a sporting rifle he had not fired in over two

years, a first-aid kit and the contents of his medicine chest. He dumped the

stuff from his desk into a carton, shoved it into the back seat along with cans

and books and coats and covered the plunder with all the blankets in the house.

They went back up the rickety stairs for a last check.

"Potty-where's

your chart?"

"Rolled up on

the back seat shelf. I guess that's all-hey, wait a minute!" He went to a

shelf over his desk and began taking down small, sober-looking magazines.

"I dern near left behind my file of The Western Astronomer and of the

Proceedings of the Variable Star Association."

"Why take

them?"

"Huh? I must

be nearly a year behind on both of them. Now maybe I'll have time to

read."

"Hmm . . .

Potty, watching you read professional journals is not my notion of a

vacation."

"Quiet,

woman! You took Winnie; I take these."

She shut up and

helped him. He cast a longing eye at his electric calculator but decided it was

too much like the White Knight's mouse trap. He could get by with his slide

rule.

As the car

splashed out into the street she said, "Potty, how are you fixed for

cash?"

"Huh? Okay, I

guess."

"I mean,

leaving while the banks are closed and everything." She held up her purse.

"Here's my bank. It isn't much, but we can use it."

He smiled and

patted her knee. "Stout fellow! I'm sitting on my bank; I started turning

everything to cash about the first of the year."

"Oh. I closed

out my bank account right after we met."

"You did? You

must have taken my maunderings seriously."

"I always

take you seriously."

Mint Canyon was a

five-mile-an-hour nightmare, with visibility limited to the tail lights of the

truck ahead. When they stopped for coffee at Halfway, they confirmed what

seemed evident: Cajon Pass was closed and long-haul traffic for Route 66 was

being detoured through the secondary pass. At long, long last they reached the

Victorville cut-off and lost some of the traffic-a good thing, as the

windshield wiper on his side had quit working and they were driving by the

committee system. Just short of Lancaster she said suddenly, "Potty, is

this buggy equipped with a snorkel?"

"Nope."

"Then we had

better stop. But I see a light off the road."

The light was an

auto court. Meade settled the matter of economy versus convention by signing

the book herself; they were placed in one cabin. He saw that it had twin beds

and let the matter ride. Meade went to bed with her Teddy bear without even

asking to be kissed goodnight. It was already gray, wet dawn.

They got up in the

late afternoon and decided to stay over one more night, then push north toward

Bakersfield. A high pressure area was alleged to be moving south, crowding the

warm, wet mass that smothered Southern California. They wanted to get into it.

Breen had the wiper repaired and bought two new tires to replace his ruined

spare, added some camping items to his cargo, and bought for Meade a .32

automatic, a lady's social-purposes gun; he gave it to her somewhat sheepishly.

"What's this

for?"

"Well, you're

carrying quite a bit of cash."

"Oh. I

thought maybe I was to use it to fight you off."

"Now,

Meade-"

"Never mind.

Thanks, Potty."

They had finished

supper and were packing the car with their afternoon's purchases when the quake

struck. Five inches of rain in twenty-four hours, more than three billion tons

of mass suddenly loaded on a fault already overstrained, all cut loose in one

subsonic, stomach-twisting rumble.

Meade sat down on

the wet ground very suddenly; Breen stayed upright by dancing like a logroller.

When the ground quieted down somewhat, thirty seconds later, he helped her up.

"You all right?"

"My slacks

are soaked." She added pettishly, "But, Potty, it never quakes in wet

weather. Never."

"It did this

time."

"But-"

"Keep quiet,

can't you?" He opened the car door and switched on the radio, waited

impatiently for it to warm up. Shortly he was searching the entire dial.

"Not a confounded Los Angeles station on the air!"

"Maybe the

shock busted one of your tubes?"

"Pipe

down." He passed a squeal and dialed back to it: "-your Sunshine

Station in Riverside, California. Keep tuned to this station for the latest

developments. It is as of now impossible to tell the size of the disaster. The

Colorado River aqueduct is broken; nothing is known of the extent of the damage

nor how long it will take to repair it. So far as we know the Owens River

Valley aqueduct may be intact, but all persons in the Los Angeles area are

advised to conserve water. My personal advice is to stick your washtubs out

into this rain; it can't last forever. If we had time, we'd play Cool Water,

just to give you the idea. I now read from the standard disaster instructions,

quote: 'Boil all water. Remain quietly in your homes and do not panic. Stay off

the highways. Cooperate with the police and render-' Joe! Joe! Catch that

phone! '-render aid where necessary. Do not use the telephone except for-'

Flash! an unconfirmed report from Long Beach states that the Wilmington and San

Pedro waterfront is under five feet of water. I re- peat, this is unconfirmed.

Here's a message from the commanding general, March Field: 'official, all

military personnel will report-' "

Breen switched it

off. "Get in the car."

"Where are we

going?"

"North."

"We've paid

for the cabin. Should we-"

"Get

in!"

He stopped in the

town, managed to buy six five-gallon-tins and a jeep tank. He filled them with

gasoline and packed them with blankets in the back seat, topping off the mess

with a dozen cans of oil. Then they were rolling.

"What are we

doing, Potiphar?"

"I want to

get west on the valley highway."

"Any

particular place west?"

"I think so.

We'll see. You work the radio, but keep an eye on the road, too. That gas back

there makes me nervous."

Through the town

of Mojave and northwest on 466 into the Tehachapi Mountains-Reception was poor

in the pass but what Meade could pick up confirmed the first impression-worse

than the quake of '06, worse than San Francisco, Managua, and Long Beach taken

together.

When they got down

out of the mountains it was clearing locally; a few stars appeared. Breen swung

left off the highway and ducked south of Bakersfield by the county road,

reached the Route 99 superhighway just south of Greenfield. It was, as he had

feared, already jammed with refugees; he was forced to go along with the flow

for a couple of miles before he could cut west at Greenfield to- ward Taft.

They stopped on the western outskirts of the town and ate at an all-night

truckers' joint.

They were about to

climb back into the car when there was suddenly "sunrise" due south.

The rosy light swelled almost instantaneously, filled the sky, and died; where

it had been a red-and-purple pillar of cloud was mounting, mountingspreading to

a mushroom top.

Breen stared at

it, glanced at his watch, then said harshly, "Get in the car."

"Potty-that

was . . . that was"

"That

was-that used to be-Los Angeles. Get in the car!"

He simply drove

for several minutes. Meade seemed to be in a state of shock, unable to speak.

When the sound reached them he again glanced at his watch. "Six minutes

and "nineteen seconds. That's about right."

"Potty-we

should have brought Mrs. Megeath."

"How was I to

know?" he said angrily. "Anyhow, you can't transplant an old tree. If

she got it, she never knew it."

"Oh, I hope

so!"

"Forget it;

straighten out and fly right. We're going to have all we can do to take care of

ourselves. Take the flashlight and check the map. I want to turn north at Taft

and over toward the coast."

"Yes,

Potiphar."

"And try the

radio."

She quieted down

and did as she was told. The radio gave nothing, not even the Riverside

station; the whole broadcast range was covered by a curious static, like rain

on a window. He slowed down as they approached Taft, let her spot the turn

north onto the state road, and turned into it. Almost at once a figure jumped

out into the road in front of them, waved his arms violently. Breen tromped on

the brake.

The man came up on

the left side of the car, rapped on the window; Breen ran the glass down. Then

he stared stupidly at the gun in the man's left hand. "Out of the

car," the stranger said sharply. "I've got to have it." He

reached inside with his right hand, groped for the door lever.

Meade reached

across Breen, stuck her little lady's gun in the man's face, pulled the

trigger. Breen could feel the flash on his own face, never noticed the report.

The man looked puzzled, with a neat, not-yet-bloody hole in his upper lip-then

slowly sagged away from the car.

"Drive

on!" Meade said in a high voice.

Breen caught his

breath. "Good girl-"

"Drive on!

Get rolling!"

They followed the

state road through Los Padres National Forest, stopping once to fill the tank

from their cans. They turned off onto a dirt road. Meade kept trying the radio,

got San Francisco once but it was too jammed with static to read. Then she got

Salt Lake City, faint but clear: "-since there are no reports of anything

passing our radar screen the Kansas City bomb must be assumed to have been

planted rather than delivered. This is a tentative theory but-" They

passed into a deep cut and lost the rest.

When the squawk

box again came to life it was a new voice: "Conelrad," said a crisp

voice, "coming to you over the combined networks. The rumor that Los

Angeles has been hit by an atom bomb is totally unfounded. It is true that the

western metropolis has suffered a severe earthquake shock but that is all.

Government officials and the Red Cross are on the spot to care for the victims,

but-and I repeat-there has been no atomic bombing. So relax and stay in your

homes. Such wild rumors can damage the United States quite as much as enemy's

bombs. Stay off the highways and listen for-" Breen snapped it off.

"Somebody,"

he said bitterly, "has again decided that 'Mama knows best.' They won't

tell us any bad news."

"Potiphar,"

Meade said sharply, "that was an atom bomb . . . wasn't it?"

"It was. And

now we don't know whether it was just Los Angeles-and Kansas City-or all the

big cities in the country. All we know is that they are lying to us."

"Maybe I can

get another station?"

"The hell

with it." He concentrated on driving. The road was very bad.

As it began to get

light she said, "Potty-do you know where we're going? Are we just keeping

out of cities?"

"I think I

do. If I'm not lost." He stared around them.

"Nope, it's

all right. See that hill up forward with the triple gendarmes on its

profile?"

"Gendarmes?"

"Big rock

pillars. That's a sure landmark. I'm looking for a private road now. It leads

to a hunting lodge belonging to two of my friends-an old ranch house actually,

but as a ranch it didn't pay."

"Oh. They

won't mind us using it?"

He shrugged.

"If they show up, we'll ask them. If they show up. They lived in Los

Angeles, Meade."

"Oh. Yes, I

guess so."

The private road

had once been a poor grade of wagon trail; now it was almost impassable. But

they finally topped a hogback from which they could see almost to the Pacific,

then dropped down into a sheltered bowl where the cabin was. "All out,

girl. End of the line."

Meade sighed. "It

looks heavenly."

"Think you

can rustle breakfast while I unload? There's probably wood in the shed. Or can

you manage a wood range?"

"Just try

me."

Two hours later

Breen was standing on the hogback, smoking a cigarette, and staring off down to

the west. He wondered if that was a mushroom cloud up San Francisco way?

Probably his imagination, he decided, in view of the distance. Certainly there

was nothing to be seen to the south.

Meade came out of

the cabin. "Potty!"

"Up

here."

She joined him,

took his hand, and smiled, then snitched his cigarette and took a deep drag.

She expelled it and said, "I know it's sinful of me, but I feel more

peaceful than I have in months and months."

"I

know."

"Did you see

the canned goods in that pantry? We could pull through a hard winter

here."

"We might

have to."

"I suppose. I

wish we had a cow."

"What would

you do with a cow?"

"I used to

milk four cows before I caught the school bus, every morning. I can butcher a

hog, too."

"I'll try to

find one."

"You do and

I'II manage to smoke it." She yawned. "I'm suddenly terribly

sleepy."

"So am I. And

small wonder."

"Let's go to

bed."

"Uh, yes.

Meade?"

"Yes,

Potty?"

"We may be

here quite a while. You know that, don't you?"

"Yes,

Potty."

"In fact it

might be smart to stay put until those curves all start turning up again. They

will, you know."

"Yes. I had

figured that out."

He hesitated, then

went on, "Meade . . . will you marry me?"

"Yes."

She moved up to him.

After a time he

pushed her gently away and said, "My dear, my very dear, uh-we could drive

down and find a minister in some little town?"

She looked at him

steadily. "That wouldn't be very bright, would it? I mean, nobody knows

we're here and that's the way we want it. And besides, your car might not make

it back up that road."

"No, it

wouldn't be very bright. But I want to do the right thing."

"It's all

right. Potty. It's all right."

"Well, then .

. . kneel down here with me. Well say them together."

"Yes,

Potiphar." She knelt and he took her hand. He closed his eyes and prayed

wordlessly.

When he opened

them he said, "What's the matter?"

"Uh, the

gravel hurts my knees."

"Well stand

up, then."

"No. Look,

Potty, why don't we just go in the house and say them there?"

"Hub? Hells

bells, woman, we might forget to say them entirely. Now repeat after me: I,

Potiphar, take thee, Meade-"

"Yes,

Potiphar. I, Meade, take thee, Potiphar-"

III

"OFFICIAL: STATIONS WITHIN RANGE RELAY TWICE. EXECUTIVE BULLETIN

NUMBER NINE-ROAD LAWS PREVIOUSLY PUBLISHED HAVE BEEN IGNORED IN MANY INSTANCES.

PATBOLS ARE ORDERED TO SHOOT WITHOUT WARNING AND PROVOST MARSHALS ABE DIBECTED

TO USE DEATH PENALTY FOR UNAUTHORIZED POSSESSION OF GASOLINE. B.W. AND

RADIATION QUARANTINE REGULATIONS PREVIOUSLY ISSUED WILL BE RIGIDLY ENFORCED.

LONG LIVE THE UNITED STATES! HARLEY J. NEAL, LIEUTENANT GENERAL, ACTING CHIEF

OF GOVERNMENT. ALL STATIONS RELAY TWICE."

"THIS IS THE FREE RADIO AMERICA RELAY NETWOBK. PASS THIS ALONG,

BOYS! GOVERNOR BRANDLEY WAS SWORN IN TODAY AS PRESIDENT BY ACTING CHIEF JUSTICE

ROBERTS UNDER THE RULE-OF-SUCCESSION. THE PRESIDENT NAMED THOMAS DEWEY AS

SECRETARY OF STATE AND PAUL DOUGLAS AS SECRETARY OF DEFENSE. HIS SECOND

OFFICIAL ACT WAS TO STRIP THE RENEGADE NEAL OF RANK AND TO DIRECT HIS ARREST BY

ANY CITIZEN OR OFFICIAL. MORE LATER. PASS THE WORD ALONG.

"HELLO, CQ, CQ, CQ. THIS IS W5KMR, FREEPORT, QRR, QRR! ANYBODY

READ ME? ANYBODY? WE'RE DYING LIKE FLIES DOWN HERE. WHAT'S HAPPENED? STARTS

WITH FEVER AND A BURNING THIRST BUT YOU CAN'T SWALLOW. WE NEED HELP. ANYBODY

BEAD ME? HELLO, CQ 75, CQ 75 THIS IS W5 KILO METRO ROMEO CALLING QRR AND CQ 75.

BY FOR SOMEBODY. ... ANYBODY!!!"

"THIS IS THE LORD'S TIME, SPONSORED BY SWAN'S ELIXIR, THE TONIC

THAT MAKES WAITING FOR THE KINGDOM OF GOD WORTHWHILE. YOU ARE ABOUT TO HEAR A

MESSAGE OF CHEER FROM JUDGE BROOMFIELD, ANOINTED VICAR OF THE KINGDOM ON EABTH.

BUT FIRST A BULLETIN: SEND YOUR CONTRIBUTIONS TO 'MESSIAH,' CLINT, TEXAS. DON'T

TRY TO MAIL THEM: SEND THEM BY A KINGDOM MESSENGER OR BY SOME PILGRIM

JOURNEYING THIS WAY. AND NOW THE TABERNACLE CHOIR FOLLOWED BY THE VOICE OF THE

VICAR ON EARTH-"

"-THE FIRST SYMPTOM IS LITTLE RED SPOTS IN THE ARMPITS. THEY ITCH.

PUT 'EM TO BED AT ONCE AND KEEP 'EM COVERED UP WARM. THEN GO SCRUB YOUBSELF AND

WEAR A MASK: WE DON'T KNOW YET HOW YOU CATCH IT. PASS IT ALONG, ED."

"-NO NEW LANDINGS REPORTED ANYWHERE ON THIS CONTINENT. THE

PARATROOPERS WHO ESCAPED THE ORIGINAL SLAUGHTER ARE THOUGHT TO BE HIDING OUT IN

THE POCONOS. SHOOT-BUT BE CAREFUL; IT MIGHT BE AUNT TESSIE. OFF AND CLEAR,

UNTIL NOON TOMORROW-"

The curves were

turning up again. There was no longer doubt in Breen's mind about that. It

might not even be necessary to stay up here in the Sierra Madres through the

winter-though he rather thought they would. He had picked their spot to keep

them west of the fallout; it would be silly to be mowed down by the tail of a

dying epidemic, or be shot by a nervous vigilante, when a few months' wait

would take care of everything.

Besides, lie had

chopped all that firewood. He looked at his calloused hands-he had done all

that work and, by George, he was going to enjoy the benefits!

He was headed out

to the hogback to wait for sunset and do an hour's reading; he glanced at his

car as he passed it, thinking that he would like to try the radio. He

suppressed the yen; two thirds of his reserve gasoline was gone already just

from keeping the battery charged for the radio-and here it was only December.

He really ought to cut it down to twice a week. But it meant a lot to catch the

noon bulletin of Free America and then twiddle the dial a few minutes to see

what else he could pick up.

But for the past

three days Free America had not been on the air-solar static maybe, or perhaps

just a power failure. But that rumor that President Brandley had been

assassinated-while it hadn't come from the Free radio . . . and it hadn't been

denied by them, either, which was a good sign. Still, it worried him.

And that other

story that lost Atlantis had pushed up during the quake period and that the

Azores were now a little continent-almost certainly a hang-over of the

"silly season" but it would be nice to hear a follow-up.

Rather sheepishly

he let his feet carry him to the car. It wasn't fair to listen when Meade

wasn't around. He warmed it up, slowly spun the dial, once around and back. Not

a peep at full gain, nothing but a terrible amount of static. Served him right.

He climbed the

hogback, sat down on the bench he had dragged up there-their "memorial

bench," sacred to the memory of the time Meade had hurt her knees on the

gravel-sat down and sighed. His lean belly was stuffed with venison and corn

fritters; he lacked only tobacco to make him completely happy. The evening

cloud colors were spectacularly beautiful and the weather was extremely balmy

for December; both, he thought, caused by volcanic dust, with perhaps an assist

from atom bombs.

Surprising how

fast things went to pieces when they started to skid! And surprising how

quickly they were going back together, judging by the signs. A curve reaches

trough and then starts right back up. World War III was the shortest big war on

record-forty cities gone, counting Moscow and the other slave cities as well as

the American ones-and then whoosh! neither side fit to fight. Of course, the

fact that both sides had thrown their ICBMs over the pole through the most

freakish arctic weather since Peary invented the place had a lot to do with it,

he supposed. It was amazing that any of the Russian paratroop transports had

gotten through at all.

He sighed and

pulled the November 1951 copy of the Western Astronomer out of his pocket.

Where was he? Oh, yes, Some Notes on the Stability of G-Type Stars with

Especial Reference to Sol, by A. G. M. Dynkowski, Lenin Institute, translated

by Heinrich Ley, F. R. A. S. Good boy, Ski-sound mathematician. Very clever

application of harmonic series and tightly reasoned. He started to thumb for

his place when he noticed a footnote that he had missed. Dynkowski's own name

carried down to it: "This monograph was denounced by Pravda as romantic

reactionariism shortly after it was published. Professor Dynkowski has been

unreported since and must be presumed to be liquidated,"

The poor geek!

Well, he probably would have been atomized by now anyway, along with the goons

who did him in. He wondered if they really had gotten all the Russki

paratroopers? Well, he had killed his quota; if he hadn't gotten that doe within

a quarter mile of the cabin and headed right back, Meade would have had a bad

time. He had shot them in the back, the swine! and buried them beyond the

woodpile-and then it had seemed a shame to skin and eat an innocent deer while

those lice got decent burial. Aside from mathematics, just two things worth

doing-kill a man and love a woman. He had done both; he was rich.

He settled down to

some solid pleasure. Dynkowski was a treat. Of course, it was old stuff that a

G-type star, such as the sun, was potentially unstable; a G-O star could

explode, slide right off the Russell diagram, and end up as a white dwarf. But

no one before Dynkowski had defined the exact conditions for such a

catastrophe, nor had anyone else devised mathematical means of diagnosing the

instability and describing its progress.

He looked up to

rest his eyes from the fine print and saw that the sun was obscured by a thin

low cloud-one of those unusual conditions where the filtering effect is just

right to permit a man to view the sun clearly with the naked eye. Probably

volcanic dust in the air, he decided, acting almost like smoked glass.

He looked again.

Either he had spots before his eyes or that was one fancy big sun spot. He had

heard of being able to see them with the naked eye, but it had never happened

to him. He longed for a telescope.

He blinked. Yep,

it was still there, upper right. A big spot-no wonder the car radio sounded

like a Hitler speech. He turned back and continued on to the end of the

article, being anxious to finish before the light failed. At first his mood was

sheerest intellectual pleasure at the man's tight mathematical reasoning. A 3%

imbalance in the solar constant-yes, that was standard stuff; the sun would

nova with that much change. But Dynkowski went further; by means of a novel

mathematical operator which he had dubbed "yokes" he bracketed the

period in a star's history when this could happen and tied it down further with

secondary, tertiary, and quaternary yokes, showing exactly the time of highest

probability. Beautiful! Dynkowski even assigned dates to the extreme limit of

his primary yoke, as a good statistician should.

But, as he went

back and reviewed the equations, his mood changed from intellectual to

personal. Dynkowski was not talking about just any G-O star; in the latter part

he meant old Sol himself, Breen's personal sun, the big boy out there with the

oversized freckle on his face.

That was one hell

of a big freckle! It was a hole you could chuck Jupiter into and not make a

splash. He could see it very clearly now.

Everybody talks

about "when the stars grow old and the sun grows cold"-but it's an

impersonal concept, like one's own death. Breen started thinking about it very

personally. How long would it take, from the instant the imbalance was

triggered until the expanding wave front engulfed earth? The mechanics couldn't

be solved without a calculator even though they were implicit in the equations

in front of him. Half an hour, for a horseback guess, from incitement until the

earth went phutt!

It hit him with

gentle melancholy. No more? Never again? Colorado on a cool morning . . . the

Boston Post road with autumn wood smoke tanging the air . . . Bucks county

bursting in the spring. The wet smells of the Fulton Fish Market-no, that was

gone already. Coffee at the Morning Call. No more wild strawberries on a

hillside in Jersey, hot and sweet as lips. Dawn in the South Pacific with the

light airs cool velvet under your shirt and never a sound but the chuckling of

the water against the sides of the old rust bucket-what was her name? That was

a long time ago-the S. S. Mary Brewster.

No more moon if

the earth was gone. Stars-but no one to look at them.

He looked back at

the dates bracketing Dynkowski's probability yoke. "Thine Alabaster Cities

gleam, undimmed by-"

He suddenly felt

the need for Meade and stood up.

She was coming out

to meet him. "Hello, Potty! Safe to come in now-I've finished the

dishes."

"I should

help."

"You do the

man's work; I'll do the woman's work. That's fair." She shaded her eyes.

"What a sunset! We ought to have volcanoes blowing their tops every

year."

"Sit down and

we'll watch it."

She sat beside him

and he took her hand. "Notice the sun spot? You can see it with your naked

eye."

She stared.

"Is that a sun spot? It looks as if somebody had taken a bite out of

it."

He squinted his

eyes at it again. Damned if it didn't look bigger!

Meade shivered.