"....Used to be addicted to science fiction and read shelves of it, but now when she read at all it was mostly English murder mysteries, the country house with the body in the library and butlers who had or hadn't done it. "I don't really give a damn who did it," she said. "I just like to slip into a world where everybody's polite and well-spoken and even the violence is neat and almost gentle. And everything works out in the end."

"Like life itself."

"Especially on West Fifty-first Street."

I talked a little about the search for Paula Hoeldtke and about my work in general. I said it wasn't much like her genteel English mysteries. The people weren't that polite, and everything wasn't always resolved at the end. Sometimes it wasn't even clear where the end was.

"I like it because I get to use some of my skills, though I might be hard put to tell you exactly what they are. I like to dig and pick at things until you begin to see some sort of pattern in the clutter."

"You get to be a righter of wrongs. A slayer of dragons."

"Most of the wrongs never get righted. And it's hard to get close enough to the dragons to slay them."

"Because they breathe fire?"

"Because they're the ones in the castles," I said. "With moats around them, and the drawbridge raised."

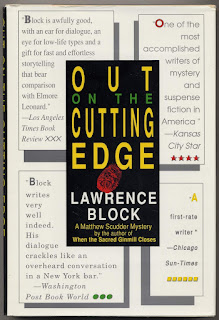

Out on the Cutting Edge by Lawrence Block (1989).

Have you ever read a novel so good you were scared to read another by the same author?

It has happened to me, but only a few times. Earthly Powers by Anthony Burgess was one. The Stand by Stephen King was another. It was never simply a question of craftsmanship. It came down to emotional involvement with the characters and the story that the writer built with their unerring craftsmanship.

I've read a dozen Lawrence Block novels, mostly his breezier output: Tanner (a kind of quirky spy), Rhodenbarr (a clever thief continually thwarted by bigger villains against whom he must turn the tables), and Keller (because if Block had to write about a man in midlife crisis, it would have to be a hit man).

Why no Matthew Scudder novels? For one thing, I dislike most U.S. private eye novels written in the last four decades. They are typically dark, cynical, and too easy on themselves; writers are usually too indulgent to their detective. And the mystery itself, the puzzle, is usually weak and camouflaged with nonsense, winning praise for "depth" from a Charlie Rose or a Terry Gross. (Plus, descriptions on Scudder back covers make the tales sound unremittingly grim.)

[N.B, My favorite detective novels are Unnatural Death by Dorothy L. Sayers and Three Act Tragedy by Agatha Christie. On a different day I might say Red Harvest by Hammett or 32 Cadillacs by Joe Gores.]

I read two of Block's wonderful collections this week: The Liar's Bible and The Liar's Companion. They comprise old columns from Writer's Digest. (I used to read that magazine as a teen in the early 1980s because I wanted to write fiction.) In several columns from the late 80s he used the composition of Out On the Cutting Edge as an example. The plot sounded intriguing, so I started my Matthew Scudder itinerary there.

Out On the Cutting Edge gives the reader two different types of mystery tale. Solving the disappearance of Paula Hoeldtke is the urban U.S. private dick mystery. Investigating the death of Eddie Dunphy is the classic English country house story, transplanted to a rent-controlled apartment building in Scudder's NYC neighborhood.

Paula Hoeldtke, a theater graduate from Muncie, Indiana, has vanished after three years in New York. Scudder is hired by her father two months after disappearance. The precious few leads are ice cold. Scudder meets her landlady and people she worked with as a waitress. He also interviews theatrical artists who hired her for bit parts and have no memory of her. (In these scenes we are given a look at the way the AIDS epidemic decimated New York's culture industry in the 1980s.)

Scudder eventually solves the Paula Hoeldtke case by persistently handing out wallet-sized photos of her until he finds a few people who react to her image. The people he meets are not nice, but they are compelling. Credit the compulsive gumshoe work ethic by Scudder.

The death of Eddie Dunphy is a different and more personal matter. Scudder has a personal stake in Eddie, a younger fellow member of AA. Eddie has been clean a year, and is coming to a crossroads: either going deeper into sobriety and owning up to past actions, or turning away out of fear of consequences.

Then Eddie dies. Magnificently, Block gives us a death which could be murder, suicide, or accident. This uncertainty eats away at Scudder. He keeps talking to people in Eddie's building. He reflects on conversations they had after meetings. Eddie has had a hard life, and Scudder burns to prove the young man died sober.

The two cases, the two styles of detective story, run parallel. Scudder learns of Paula's fate on the same day he solves the mystery of Eddie's death. Like the parallel editing in a film by Griffith, Scorsese, or P.T. Anderson, the narrative advances and resolutions come in huge crescendoing emotional waves delivered in seemingly modest prose of such a power as to make the reader weep.

As a Marxist, I was also struck by the third crime explored by Out On the Cutting Edge. The backdrop for Paula's disappearance and Eddie's death is the crime perpetrated against the people of New York City by a capitalism whose contradictions are turning murderous.

Everywhere Scudder goes, streets are filled with people driven to beggary. In Eddie's building, empty apartments are not rerented because owners want to wait and sell them as expensive co-ops.

As one character points out, every conversation between people in NYC, no matter where it begins, ends up as a conversation about real estate.

As the novel progresses, Scudder puts himself at moral hazard, but friends keep allowing him time for perspective and a saving patience, as well as the confidence to keep going his own way.

I could go on at length about the crucial and beautifully articulated characters Scudder meets while pursuing each case. I can tell you that they are the stuff of great art: they suggest the deep social reality Block pursues and carefully conveys.

You will, if you go ahead and read the book, be thankful I spoiled as little if its perfection as I did.

Jay

17 April 2018

No comments:

Post a Comment