[....] the practiced reader of tales in our genre comes to feel not merely the shiver of fear, but the shiver of aesthetic seizure. In a superior story there is a sentence, a word, a thing described, which is the high point of the preparation or the resolution. Here disquiet and vision unite to strike a powerful blow. The moment is like the "diagnostic fact" in making the passage and the tale memorable, an artistic triumph. This peculiar thrill comes, unexpected, gratuitous….

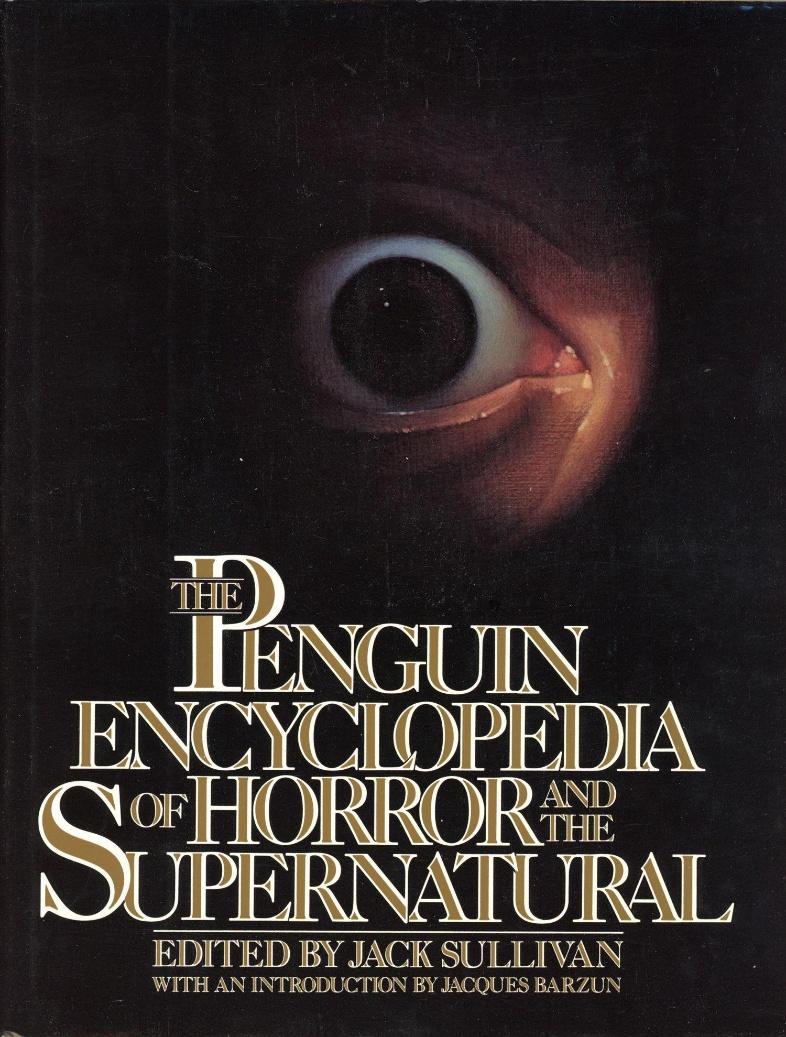

From the Introduction: The Penguin Encyclopedia of Horror and the Supernatural (1986)

Jack Sullivan, General Editor:

INTRODUCTION

THE ART AND APPEAL OF THE GHOSTLY AND GHASTLY

Why an ever-widening circle of connoisseurs and innocents seek out and read with delight stories about ghosts and other horrors has been accounted for on divers grounds, most of them presupposing complex motives in our hidden selves. That is what one might expect in an age of reckless psychologizing. It is surely simpler and sounder to adduce historical facts and literary traditions, limiting the psychology to one familiar observation: children are afraid of the dark and yet enjoy stories in which mysterious and 'horrible things happen. The aftereffect may be a somewhat heightened fear at bedtime and an occasional nightmare, but except in rare, overwrought natures, these consequences do not lessen the child's demand for this imaginative fare and paradoxical thrill.

The fear of the dark is there to begin with, though it has perhaps been reduced by the advent of electricity, which floods with dissolving light the corners and corridors once inhabited by goblins. Fear of the dark is in any case a sensible fear until one knows what the universe is capable of. Strange shapes and moving shadows and the unidentifiable creakings and sighings that houses like to emit after nightfall need to be explained and organized rationally. The eagerness for stories about those things can thus be seen as a practical attempt to put order and system into the imaginings and harden the soul against their menace: in a word, they serve as mithridate.

Of course, the stories only substitute one set of fears for another. If the sighing is due to a ghost and the creak of the stairs that seem footsteps ascending indicate its approach, there is still something formidable to be afraid of. Ghost, in Middle English goste, meant "frightening" before it came to mean the thing that frightens. Etymology does not limit meanings, but the fact remains that the ghost story is the fundamental form of the tale of horror.

This is true because the idea of a ghost and the sense of the ghastly (two words from the same root) arise from a single source: the mystery and horror of death. Among all peoples and tribes, as far back as legends and other evidences go, the strange phenomenon of a lifeless body, the sight of a being recently full of motion and will and now present and absent at the same time, has inspired the notion that what has departed is the active principle—spirit—and that it may still have business to transact on Earth. The question then is, under what conditions can it do so and with what intentions, friendly or hostile? If it is to reappear, like and yet unlike itself, it must be heeded and if possible placated.

This reappearance, moreover, fits in with another strange phenomenon, dreaming, in which we see and hear the dead as well as the distant living. Finally, ghosts and dreams alike find a ready place in the overarching thought that ascribes to gods and spirits the large events of the natural world. Thus the ghost story in its widest sense is the earliest literature, being an integral part of the earliest religion and philosophy: Cro-Magnon cave paintings, no less than the Greek And Roman myths, or the African and Oceanic, testify to this common way of handling the perplexities of life and death: the supernatural is the most natural supposition.

It is no wonder, then, that its essence and its trappings continue to stir our feelings and start our minds. We have not overcome the fear of death; on the contrary, by postponing its occurrence through hygiene and medicine, we have made it less familiar in the home and have got rid of the rituals that helped to make us accept it. Our science has also robbed many of their faith in an afterlife, and pluralism prevails —believers, atheists, and agnostics rub elbows, mutually unconvinced.

In this confusion of our day, two traditions persist: superstition and literature. Modern superstition, aping science, thrives in the many forms of pseudoscience, the most popular of which is astrology. Flying saucers come next, the by-product of space travel, which has revived the notion that other worlds are inhabited, thus extending the fantasies of science fiction—all this on top of the old fears of folklore: people shun black cats and knock on wood to avert mishaps; high-rise buildings skip numbering the thirteenth floor; and while some admit that they half-believe in ghosts, second sight, and telepathy, others join cults in which the activity of spirits is charted in detail. Disraeli was right: the characteristic of the age of science is a craving credulity.

But it is a craving, not a fulfillment. The main current of thought and behavior reaffirms disbelief in anything but material fact, which is why spirit(in any sense of the term) finds refuge in literature, in fiction. Contrariwise, in the ancient religions, the word is a weapon and poetry a practical means of defense against spirits. When the Babylonians had to fight the evil genies who come from under the Earth to defy men and the lesser gods, common prayer was not enough. The danger called for a special incantation:

Evil alu, turn thy breast and depart!

Inhabitant of the ruins, get back to thy ruins

and so on, with ritual gestures and an appeal to the benevolent Ea, in whose name the magic was performed.

A further feature of the primal story should be noted: the evil spirits are portrayed as uniting human and animal forms—claws and horns, tusks and nostrils breathing fire. There is a kind of economy in combining the fear of wild animals with the fear of malign spirits. But matching this menace is the conviction that men must and can do something to avert it. In ritual, sacrifices, and burial customs such as furnishing the dead with useful articles, the purpose is enlightened self-interest. To this day, the use of coffins reminds us of a not so remote belief that the spirit ought to be kept from wandering.

Evidently, the universal assumption is that the dead are resentful, worse than the gods, who are merely capricious. Quite literally, the ghost is out for revenge. This is especially so in his time and place the fact of natural death is not yet common knowledge. He then thinks he has been murdered and wants retribution. The Sanskrit root behind goste itself means "anger."

Such are the well-founded, ancestral ideas that inform the literary genre under discussion. Tales of horror that do not summon up ghosts or otherwise invoke the supernatural derive from the same source and rely on the same feelings as those that do: the fear and mystery of death. We can therefore discuss the essential elements of the literature and its points of particular interest to modern readers without marking off two species of terror. Under any generality, due allowance can be made for divergent characteristics.

Not that the reader needs to be equipped with a theory of horror in literature, complete with a blueprint of the mechanism by which thrills are generated. That would be to fall into the tedious error of the current critical methods. If there were, indeed, a theory and a mechanism, any journey-man writer could turn out a satisfactory product, which is notoriously not the case. Some first-rate writers who have attempted the genre have failed, and others have succeeded in this genre only. The critic notes the fact and wonders why. In proposing answers, his business is not to substitute formulas for experience, but simply to point to aspects of good work which, if lingered over, may explain and enhance the reader's pleasure.

It seems a paradox, at least on the surface, that tribes and nations that believe in ghosts do not produce a literature of horror-for-pleasure. Among ancient Greeks and Romans, the ghosts and gods that appeared to human beings did cause astonishment and fear, but the event did not violate existing beliefs; it was consistent with them. Consequently, the fear was but the anxiety to comply with divine commands. Thus Socrates was on easy terms with his daimon and the Delphic Sibyl. Dreams of the departed, omens, the left, magic transformations into stones or trees gave a shock, perhaps; the event was portentous but not impossible. In Apuleius, the hero is turned into an ass by a spell, but his adventures are not fearful, only strange. When in Virgil Mercury appears to Aeneas and orders him to get a move on, the feeling conveyed is that of startled obedience. But note the effect of modernity: the same incident, reproduced in Berlioz's music drama, Les Troyens, inspires the composer with music that gives us a shiver of terror. The same is true in the operas of Gluck and Mozart whenever the supernatural comes into play. In other words, enlightenment does not diminish, it increases the fearsome. The supernatural, so natural to the ancients, has become for us moderns the anti-natural.

That difference explains how the ghostly supplies a resource of great power for literature and why the specialized genre took its rise in the eighteenth century, the age of reason and of unbelievers. The triumph of science, the system of Newton and Locke, left no room for the super-natural. God had designed the machine, pushed the starting button, and then gone into well-earned retirement. Therefore, no ghosts. Dr. Johnson and other enlightened men made short work of the Cock Lane Apparition by spending the night in its reported haunts and summoning it to show up or shut up.

This confident skepticism is required by the genre that exploits the supernatural. To feel the unease aimed at in the ghost story, one must start by being certain that there is no such thing as a ghost. Critics who apply to the situation Coleridge's phrase about the playgoer's suspension of disbelief fail to see that it does not fit. Disbelief must persist, not be suspended, if every successive touch in the tale is to be strongly felt. Whenever we can say, "Why, yes, that's what ghosts regularly do," we know we are reading a poor story, one that goes through the familiar motions and delivers only "fear clichés."

Granting that we had better be naturalistic in order to relish tales of the supernatural, we must still ask why the eighteenth century felt the desire to temper its rationality with mysteries it did not believe in. Why did it revive the despised medieval superstitions peopled with devils, witches, and ghosts, when it had Candide and other satirical fictions by Voltaire, the lifelike adventures of Gil Blas and Tom Jones, and the subtle explorations of feeling by Goldsmith, Richardson, and Sterne?

To ask is really to expect an answer to the question, How did European Neoclassicism come to an end and make way for Romanticism? An attempt to describe that great turning will be found later in this volume under the heading "Romanticism," which deals mainly with the "dark side of Nature." Here it is enough to suggest that intellect and art finally exhaust the possibilities of any outlook. It becomes a bore. And even at its height, a cultural mood coexists with its opposite—a sort of suppressed minority party. Out of it come eccentrics who, one by one, break through the orthodoxy and reinstate the elements it excluded. The ground is thus prepared for the next phase of thought and culture. The tale of ghosts and kindred Gothic horrors was one such element restored in the passage from Neoclassic to Romantic.

In our genre that transition is well mirrored in the change between the early examples of "Gothic" horror and our present practice. From the works of Horace Walpole, the originator, and of Clara Reeve or Mrs. Radcliffe, the first true master of the genre, we retain hardly more than the intention to terrify by manifestations of the uncanny. What these authors exhibit would not terrify us and the "rational explanations" they usually feel bound to offer at the end would not convince— only evoke disgust at being let down.

In other words, these initiators were, like us, trying to make the best of both worlds, but they wanted to return to the solid comforts of the fully rational. We, on the contrary, want the terrors to shake our faith in the uniformity of nature. We refuse to have our ghosts explained away lest the strong emotion they engender should be cut short and matter-of-fact reason plunge us back into our everyday materialism. The fiction is meant to revive, in the most adult way, our childish fears.

There are thus three phases in mankind's attitude toward spirit return. The first is anxious but practical. When Saul consulted the Witch of Endor, he was eager for her to perform her news gathering service and unafraid of it. Likewise, the miracles of Jesus astonished but did not frighten.

As for medieval Satanism, it was a threat to salvation, willfully incurred, and the guiltless could exorcise all its evils. The second phase, that of the secular philosopher liberated by science, begins by a dismissal of any belief in spirits but ends by toying with them in a literary way, teasing the reader with a What if—? and quickly scurrying back to common sense at the end. The third is our present sophisticated mode, in which a new shade of feeling, the aesthetic, enters in to offer us not a denial but an extension of experience.

The modern mind has learned how to live on several incompatible levels, and the level of the uncanny—literally, the unknown—affords us a rare pleasure, that of not knowing what to think, what to do. The ghostly, like the other arts, restores our awareness of how limited the workaday world really is.

The modern imagination has indeed been well trained by psychiatry and avant-garde novels to accept the weird and horrible. Often, these works are themselves beyond rational comprehension. But stories of the supernatural—even the subtlest—are accessible to the common reader; they make fewer demands on the intellect than on the sensibility. This is to say that they make increasing demands on the writer. So much has been produced in the genre during the last two hundred years that some of the best inventions have worn thin. True, the settings and the props are still serviceable, but the effects must be continually renewed and refined, surprise being a necessary ingredient of fear.

For the rest, the "Gothic" paraphernalia is still potent. The crypt, the tomb in church or graveyard, the black-letter folio or crabbed manuscript—in short any relics or appurtenances of the dead continue to legitimize apparitions, forewarnings of dire events, dealings with the unseen, causeless movements of objects, pacts with the devil, witchery, phantasms, werewolves, and vampires. In addition to which, pagan mythology, and especially the Great God Pan, are good for joyful returns to unbridled animalism, always puritanically punished by death. But these repeating elements have ceased to constitute the main interest. They have given place to a preoccupation with the sophisticated mind's response to what the manifestations imply. Fear is present, but introspection goes on and its pulses of doubt and alarm and grasp of significance furnish the interest. The traditional background is of importance chiefly as a sign that permanent forces are at work—history crossing and recrossing eternity. The best ghosts have ancient grievances, the Devil fell aeons ago, and a haunted house does not acquire its status till tenant after tenant has fled in terror.

Of course, variations are endlessly possible. In Henry James's typically historical last novel. The Sense of the Past, the manifestations are fairly gentle and the past not very remote. The surprise consists in the investigator's being himself transported backward in time, while those he meets in the ancient house vaguely detect his modernity. Owing to the Jamesian introspection, the tale is eerie rather than horrifying, but it is an excellent example of the kind of twist that the writer of our century must supply.

Another variant, in keeping with one tendency of modern fiction, is obtained by juxtaposing the utterly commonplace with the macabre. The street, the office, the commuter train, the summer bungalow, the kitchen are exploited, on the same principle as that which makes skepticism the best terrain for mystery. The more ordinary the place or routine, the more shocking the untoward happening. In one story whose title escapes me, a woman who has already discovered alarming anomalies on returning to her house after the holidays examines the labeled canisters in her kitchen and exclaims: "The sugar's in 'Rice'!" A small point but, rightly led up to, electrifying. The tales, long and short, by Celia Fremlin (who herself has worked for hire as a part-time housekeeper) are extraordinarily successful at making the most of harmless deviations from the norm. Hers is the minimal art in the genre.

More explicitly, but still bypassing the "Gothic" and Satanic, a great many modern tales simply pose the question: This happened—how was it possible? For example, in Anne Bridge's "The Buick Saloon," a diplomat's wife, having just rejoined her husband in Peking, buys a reconditioned car in which she, and she alone, hears a woman's endearments, uttered in French to "Jacques." She traces the former owner and her frequent trips to a secluded spot, and there finds proof of meetings with the newcomer's own husband, James. Even more deft, Arthur Schnitzler's superb tale 'The Baron" accounts for the death of the protagonist by the joint effect of his vulnerability and another man's superstition, seconded by the femme fatale. It is a tour de force in the natural mode of using the anti-natural.

Be the effect small or large, ancient or novel, what is essential to disquiet is the sense of a hidden will, preferably evil in intention. Whether the particular motive is retribution, as in DeQuincey's "The Avenger"; pure malignity, as in Wakefield's "He Cometh and He Passeth By"; vampirism (a vicious self-serving act) as in F. G. Loring's 'The Tomb of Sarah"; or lust served by the Black Mass, as in Margaret Irwin's "The Earlier Service," the will behind the deed must spell danger to the living. That generality links the cave dweller, who fears the return of the dead, with twentieth-century man, who is shaken by the thought that the laws of nature may suffer exceptions. If it can be shown that nobody entered the house, then the fact that sugar's in the rice is as appalling as if the wicked uncle, buried long since, glared malevolently over the foot of the bed. It is also a modern feature of the genre that the harm intended to mortals may as easily be justified punishment as sheer anger and ill will: morality no longer governs our art.

As for comments by the author about the human mind or the ways of society, they can throw light on important aspects of life, but they must remain sidelights, for ghost and horror fiction do not belong under the same heading as the novel, which is preeminently social and psychological; they belong to the genus "tale," which is strictly literary, though not incapable of symbolism or wisdom.

These considerations of substance bring us to those of technique. In the literature of natural or supernatural terror, the writer's main concern is with detail. The principle was well stated by E. G. Swain: 'This will appear to the reader a record of the merest trifles, but all readers will accept the reminder that there is no such thing as a trifle ... it has that appearance only so long as it stands alone" ('The Rockery"). The ghost story is in this respect as delicate a construction as the detective story. It is notorious that both genres appeal to much the same audience, not (as is often said) for sensation's sake, but for the literary qualities of invention and craftsmanship. Connoisseurs judge the new work by the originality, aptness, and elegant placing of the significant details. So true is this view of the two genres that Joan Kahn, following the lead of Dorothy Sayers, has successfully published half a dozen anthologies that combine detection, true crime, and the supernatural. Among storytellers, as everybody knows, Poe and Conan Doyle stand out as masters in both these fictional kinds. More recent practitioners in the two genres include Mary Fitt, C. H. B. Kitchin, L. A. G. Strong, and of course Dorothy Sayers herself.

The first rule about frightening details, picturesque or commonplace, is: restraint. The King of Terrors or his deputy must be frugal in his display or he will saturate his victim's consciousness, which is also the reader's, leaving no room for dreadful doubt as to the superior power. The spacing between shocks, too, must follow the subtle law of "beats"—the ebb and flow of emotional intentness. Compare Algernon Blackwood and M. R. James—both great inventors—and you find Blackwood spoiling splendid schemes by neglecting this rule of rhythm. He applies the pressure too steadily.

As in crime fiction, once more, an original idea fully developed may not be used by another hand. After M. R. James's little masterpiece "The Mezzotint," there is no thrill or pleasure in "The Man with the Roller," by E. C. Swain, the otherwise gifted author of The Stoneground Ghost Tales. In another collection, Nine Ghosts, R. H. Malden declares himself, like Swain, a disciple of James's, and he proves his claim so far that only one of his nine, "The Priest's Brass," has any power. The dark lane, the clearing in the woods are as repeatable in the ghost talc as the roadside ditch, the library, or the foot stairs in murder and detection, but not what may be called, in either genre, the diagnostic net.

And the surrounding facts, even when not original, must convince by accurate placing, as well as inherent fitness. In Elizabeth Bowen's "Hand in Glove," the long gloves on which she relies for her denouement make the revenge ludicrous and not at all scary. They come into play much too late; the normal human and social situation has kept us interested, but calm and critical, not apprehensive; and in our imagination gloves cannot escape their intrinsic flabbiness, hence their inability to strangle the wicked.

By contrast, an inadvertence in detail, as in M. R. James's "Treasure of Abbot Thomas," does not spoil our sense of fitness, even if we happen to notice the error in arithmetic: the message speaks of "a stone with seven eyes"—obviously the mystic number. And, sure enough, on the slab that conceals the treasure are the guardian eyes. But we are told they form a cross "four vertical and three across," which makes only six eyes—too bad for the power of seven!

What keeps settings and details fresh is Description, the second characteristic element of these modern genres. Before the art of the novel accustomed readers to extended descriptions, the folk reports of the supernatural were flat-footed summaries; they could have been set down in a couple of paragraphs. On the stage, in Shakespeare and others, the apparitions were forceful but brief; costume and menacing words had to do all the work. And sometimes the vision was adroitly left invisible. Defoe was the first to see that something more striking could be made of popular rumors if they were developed. In "The Apparition of Mrs. Veal" he gave a full-blown specimen of the made-up tale, elaborate in description and rich in those seemingly irrelevant little facts that create verisimilitude. That it was at the same time a successful promotional piece for a non-selling book which he involved in the narrative only adds to our appreciation of his genius.

His contemporaries in fiction, including those I mentioned earlier, did not waste time on giving visual or other particulars. The aesthetics of classicism contented itself with generalities: "a splendid palace adorned with curious carving and rich furnishings," or "a fine garden resplendent with many blooms," or "the humble abode of a charcoal burner in the woods." Like old-time movie sets, scenes were ready-made articles rolled into view with half a dozen words. Compare with those clichés Blackwood's "The Willows," where a description of the course and scenery of the Danube in Austria occupies ten pages before anything happens. Or, in a shorter work, "Wandering Willie's Tale," by Walter Scott, note the masterly effects obtained by hitting with precision the physical sense appropriate to each scene.

Since for terror descriptions must perpetually make the reader accept yet question the strange amid the familiar, the writer pursues the muse of ambiguity. He begins by establishing a solid outer shell of comfort—the clergyman's study, the lawyer's book-lined room, the well-placed camping tent, or the cozy room at the inn or club, with fortifying drinks at hand. But Soon a vague unease, a chill in the air, or else a strong shock undermines or shatters composure. No rhetorical onslaught on "bourgeois complacency" can equal it; the intrusion, fluid and elusive or sharp and violent, destroys all past security.

To deepen the disturbance, the narrator of another's misadventure or of his own starts out neutral. He reports what the documents or the tradition deliver or gives his subjective impressions, but interspersed with objective facts. In some cases one fact is enough. Thus, in Oliver Onions's "The Cigarette Case," that very object, forgotten at tea-time in an elegantly furnished house inhabited by two ladies, is found the next day where it was left—the derelict villa that has been untenanted for twenty years. Again, in Vincent O'Sullivan's "The Interval," the distraught widow consults mediums and at last gets a sight of her dead husband. He soon comes for her, picking up her slippers as he escorts her out. To the world, she lies dead in bed, "but they never could find her slippers."

Apropos of mediums, to depict the intentional summoning of the departed or any significant spirit communication is extremely risky, as the many attempts in detective stories demonstrate. There is an art to what might be called "séance fiction," and it consists in making the preparations long and precise and the manifestations brief and obscure, even if they serve plot by redirecting fear or hope.

Details and descriptions generating atmosphere go a long way to ensure an impressive story; but they are not enough for perfection. Unless every element is finely wrought and fitted, a story will not be memorable or even satisfactory. The preeminence of M. R. James is due to his extreme care in the handling of all the parts—place, time, description of natural and domestic scenes, preliminary details (including the irrelevant), disturbances of mind and matter, temporary relief from fear, varieties of speech and of evidence, action taken or repelled, and, most difficult of all, outcome on a high or low note.

Nothing less than this will make the spectacle of matter at the mercy of the impalpable generate a series of shocks to instinct and spur the reader to inward-looking thoughts. It is this fragility of the form that makes the ghost story more artful—and more productive of shivers—than the straight tale of horror. When Leiningen barely escapes being destroyed by a huge army of ants; when the young couple in the woods are attacked by numberless small birds and buried alive under a mound of feathers; when, in Arthur Machen's The Terror, the beasts of the field turn against man, we are naturally disturbed by the thought of an overturn in the relations of the human and animal kingdoms, but the means used to shake our confidence are crude. The event, for all we can tell, might come to pass, in which case it would be but a calamity, like being caught by a shark when swimming. Birds and ants and sheep would be reclassified as natural dangers, alongside tigers, avalanches, and botulism spores. A little less obvious, perhaps, is the revenge of the cat who contrives to get her human tormentor crushed to death in the notorious "iron maiden."

But even the vampires and werewolves of fiction possess too much material power to cause the Ultimate Disquiet. Stoker's Dracula is a fine piece of work chiefly by reason of its superb setting and buildup; but there is after all a cure for the blight, and the treatment as carried out methodically reminds one too much of asepsis and surgery at the nearest hospital. For a contrast, read Le Fanu's "Green Tea,'' where in one sense nothing happens, and you will find that your nerves, which only tingle at first, have acquired a long-lasting tremor.

For the modern sensibility it is not even necessary that a recital should produce at any point such symptoms of bodily fear. A choice irrationality, a mere juxtaposition of ideas will create afterimages that vibrate for a good while. For example, W. F. Harvey's "August Heat" describes a man's experience of second sight, followed by the actual sight that corresponds—his own tombstone, carved complete except for the death date. As told by this master, it is quite enough. Again, in Andrew Caldecott's masterpiece, "Branch Line to Benceston," the clock five minutes fast, and then the death as predicted, form a striking, insoluble puzzle of the most haunting kind: "they may know the answer in Benceston."

How to end is indeed an extraordinarily touchy matter. Numerous tales of high quality go on a sentence or a paragraph too long, from a desire to comment or explain, and propel the reader straight into anticlimax. E. F. Benson only seems to incur this charge in his admirable pagan tale "The Man Who Went Too Far," where the thundering finale of the death is actually topped in horror by what the stunned witness discovers on the skin of the corpse. Nowadays, what is often foolishly explained is the character of awfulness of the evil business, not some rational cause of it; though when Bulwer-Lytton in "The Haunted And the Haunters" ascribes the horror experienced by his observers to a hidden bowl of liquid on which floated a magnetic needle, he was using "science" and "explanation" without being scientific or explaining anything; he was adroitly doubling the mystery.

In any genre, the difference between a good idea merely "written up" and a memorable tale is, of course, style. But in the literature of fear, style acquires an importance far beyond that which it holds in the traditional novel. Many fine and even great novelists have used an indifferent, featureless style. The prose of Balzac, Tolstoy, or Hardy is not notable for elegance or subtlety'. What their genius led them to body forth matters more than the way they put it. In dialogue, if the novelist approximates current speech, the effect is good enough. The novel of contemporary life relies on character and the management of significant scenes, and the reader's knowledge of social realities meets the writer's vision halfway. But in the tale of ghosts and horrors, the imagination must be teased into feeling strongly what has never been experienced. Character may or may not play a part; the main offering is, as M. R. James rightly says, "those things that can hardly be put into words and that sound rather foolish if they are not properly expressed."

This principle is clear from a good many anthologized stories in which the plot or "diagnostic fact" is excellent, but the telling flat-footed. For example, the joint pursuit in Robert Bloch's "Yours Truly, Jack the Ripper" is recounted in such obvious terms that the tag line and surprise ending cause no surprise and no conviction. We have it from Raymond Chandler about tales of crime that so-called realism does not depend on facts, genuine or plausible, but wholly on style. In other words, a good writer can make you believe anything. It follows that in working up horror every word is important, and only the most conscious and skillful writers succeed. How the frequently portentous but unintelligible H. P. Lovecraft has acquired a reputation as a notable performer is explainable only by the willingness of some to take the intention for the deed and by a touching faith that words put together with confidence must have a meaning.

Even the highly inventive Blackwood frequently commits the stylistic blunder of telling us what to feel instead of causing us to feel it. In "A Haunted Island," for instance, the contriving of detail is superb, but such expressions as "I waited in an agony of suspense and agitation," "only to give place to a new and keener alarm" deflate the suspense and the alarm. One may say, "Remember the story was written in 1906, when nineteenth-century diction still prevailed." That excuse will not do. The rhetoric of any age, when it was rightly handled, produced an effect that is still potent—witness Scott, Maturin, Dickens, Allan Cunningham, Kipling, all writing earlier than 1906. A small mannerism of Blackwood's clinches the charge of stylistic weakness: he repeatedly uses the suspensive dash in the mistaken hope of heightening horror: "because it was—of stone"; silence—just behind it"; and so on by the dozen in an otherwise good tale, "The Tryst."

Where Blackwood shines, in addition to devising splendid details, is in the kind of prose poem, long or short, that writers of horror often use. I have already mentioned 'The Willows." Numerous other writers have exploited scenery and the elements to set the stage for the super- or anti-natural, whether as contrast or as preliminary menace. Perhaps the most sustained and stunning example of what I have called the prose poem for ghostly narrative is Allan Cunningham's "The Haunted Ships." The reason why metaphor and hyperbole suit the genre is clear enough: they narrow the gap between reality and the uncanny and create a doubt as to which is which. In the same way, the ill-named pathetic fallacy serves the special ends of the ghastly, for it reinstates a primitive animism; e.g. "the quiet breathing of a clock," which produces "a hush more delicate than silence." The basis of spirit-in-matter is the belief that (in Wakefield's words) "certain places, certain things, become impregnated, kinetic, sensitized." Whoever so believes abandons the crass distinction of subjective and objective, just as the actors in a ghost tale seem to know apparitions and understand their demands without actually seeing or hearing anything: communication is "from inside."

Because these ideas find proper expression in heightened language, the practiced reader of tales in our genre comes to feel not merely the shiver of fear, but the shiver of aesthetic seizure. In a superior story there is a sentence, a word, a thing described, which is the high point of the preparation or the resolution. Here disquiet and vision unite to strike a powerful blow. The moment is like the "diagnostic fact" in making the passage and the tale memorable, an artistic triumph. This peculiar thrill comes, unexpected, gratuitous, as when the guard on the battlements at Elsinore, telling how Hamlet's father's ghost appeared, throws in the words "—the bell then beating one." The moderns can do it too: in Maupassant's "Who Knows," the narrator finally approaches his own house, at one in the morning, under a fitful moon: "The great mass of trees looked like a tomb in which my house lay buried." In Dickens's "The Signalman," the teller quietly speaks of "the slow touch of a frozen finger tracing out my spine." In de la Mare's "Crewe," a different tone, that of the common man's vocabulary, does the work: "Who wants to go, I should like to ask? Early or late? And nothing known what's on the other side. Keep on this side of the tomb as long as you can. Don't Meddle with that hole . . . You can never be sure what mayn't come back out of it." This last sample incidentally restates in definitive fashion the root idea of all horror, the permanent, recurrent unknown that no algebra can solve.

De la Mare's name reminds us that the tale of horror also lends itself to the forms of verse. His own little gem "The Listeners" is a famous example, in the well-established tradition of the Romantic poets. Another and a greater work is Burns's Tam o' Shanter, which, for all its strong lashing of humor, delivers the genuine grue.

This great poem in the British tongue raises the stylistic question of dialect, either regional or peculiar to a social class. The horror story inclines to it naturally, for the testimony of simple folk easily brings out the contrast between superstition and sophisticated disbelief. But dialect must be handled with (if possible) still greater care than straight speech; and except for the Scottish, which Scott and Burns made a second language for English readers, and Irish, similarly acclimated by the playwrights of the Celtic renaissance, all others must be used in small doses. A fairly good arctic tale by Robert T. S. Lowell, "A Raft That No Man Made," is ruined by the skipper's unreadable jargon. For a model of success, see Burrage's "One Who Saw," in which the French waiter's imperfect English is done in such a way as to certify (so to speak) the reality of the woman haunting the town of Joan of Arc's death—a brilliant performance altogether.

Not Burns only; Scott also managed to combine the spectral with the laughable, and none have equaled their art. But the wholly humorous ghost crops up from time to time—in Oscar Wilde, Brander Matthews, H. G. Wells, and others. These efforts raise at most a smile, the diagnostic fact being solely an inversion of the expected: the ghost cannot cope with the living. Yet sardonic humor in the course of a serious narration is an excellent stylistic device. As DeQuincey pointed out with regard to murder, a kind of morbid mirth is a good seasoning for horror. When we read: "One shot himself in the bedroom; the other drowned in the usual way," the feigned casualness adds a bitter tang, sharpens imaginative attention.

In one branch of the literary art, our authors in general have been uncommonly weak. I refer to making up good titles. For my part I find it difficult to remember what story goes with such unevocative tags as "The Tool" or "The Face," "The Rocker" or "The Ancient." "The—" something or other does not encourage me to separate what happens in "The Ash Tree" from the troubles in "The Apple Tree," or "The Lovely Voice" from "The Lovely Lady," although the stories themselves stay clear in my mind. One can understand the writer's desire to name a common thing simply in order to increase the horror of its turning out not simple; but the expedient is self-defeating when it renders the commonplace entirely featureless. The right sort of invention in titling is not beyond human ingenuity. Think how much more vivid "The Tomb of Sarah" would appear if renamed "The Tomb of Countess Sarah"—for such was that awesome woman vampire.

True, some wonderful images have been hit upon, usually for books: "They Return at Evening," "A Warning to the Curious," "Widdershins,"* "Not Exactly Ghosts." Among stories, one title that is a stroke of genius is John Collier's "Thus I Refute Beelzy," for it combines an unforgettable allusion to Dr. Johnson's "refuting" Berkeley with the gruesome end of the dentist who tyrannized his little boy with adult reasoning. In the mode of simplicity, "What Was It?" and "Someone in the Room" are also unforgettable; and so is the phrasing that twists an ordinary idiom, as in "A Peg on Which to Hang." The list of the fitting could be extended, yet it would not begin to equal the dull, or those that flatly give away the diagnostic fact, such as "The Phantom Rickshaw."

Much the same could be said of another atmospheric element, the names of persons and places. On this score, the two Jameses, Henry and M.R., stand at opposite poles, Montague Rhodes being here the master and Henry the duffer. Let the victim of the terror by all means have a plain moniker, to help us feel his or her normality, but the site should somehow echo the "doings" and, above all, the sinister figures pastor present should carry a hint of their singular destiny: Professor Rascallo and Count Magnus live up to our hopes and their fates.

One last remark, among a host that might still be offered to the reader's consideration. Many more writers have tried their hand at the genre than one suspects or remembers, and some true masters covered in this book are regularly overlooked by anthologists. For example, Fitz-James O'Brien was an original craftsman, from whom Ambrose Bierce borrowed at least one good idea, that in "The Damned Thing." Lafcadio Hearn also fashioned a true work of art among his Chinese Ghosts. How many readers have heard of Amelia Edwards? Yet "The Four-Fifteen Express" is a respectable little tale—trains always lend enchantment to any kind of fiction.

Among die moderns whom one should make a point of seeking out are Thomas Hardy, May Sinclair, the Bensons, Lord Dunsany, Marjorie Bowen (superior to Elizabeth), Quiller-Couch, Robert Aickman, and many others whose names elicit no such ready recognition, but who have contributed notable tales. Fortunately, Everett Bleiler's extensive bibliography is now at hand to guide the seeker. The difficulty is to find—in libraries, secondhand bookshops, and old inns—the forgotten volumes in which a treasure or two lie buried.

One could—should—also ask why the one same anthology piece always represents such masters as W. W. Jacobs or W. F. Harvey; why the splendid variety of Conan Doyle's output is hardly tapped, and why the amazing storyteller Barry Pain remains virtually unknown. Equally unknown, of course, are the anonymous authors, some of whom Julian Hawthorne dug out of nineteenth-century magazines. Taken as a whole, the output from Horace Walpole to Hugh Walpole and beyond stands in need of critical study, not to erect theories upon subterranean surmises, but by using direct observation and following educated taste, as has been attempted here, to enlarge for all readers the repertory of the well-wrought and the enjoyable.

JACQUES BARZUN