When you consider what a slight part the weird plays in our moods, feelings, and lives, you can easily see how basically minor the weird tale must necessarily be. It can be art, since the sense of the uncanny is an authentic human emotion, but it is obviously a narrow and restricted form of art ….

—H.P. Lovecraft

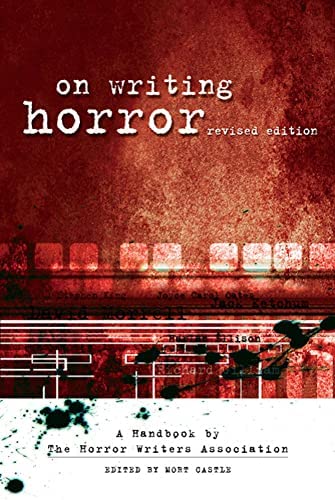

On Writing Horror: A Handbook by The Horror Writers Association

Edited by Mort Castle

(Writer's Digest Books: 2006, Revised edition)

Like many Writer's Digest publications, On Writing Horror has many contributors who, as fiction writers, amounted to also-rans. Still, there are enough real contributions in the anthology to make the book valuable. My edition seems to straddle pieces from the late 1980s and late 1990s. References to the Meese Commission and Dr. Ruth, I am sure, will quicken the pulse of very few readers today.

The horror field has certainly come a long way in the right direction since On Writing Horror first appeared. It is, I think, a stronger and more varied field.

Excerpts below are, it seemed to me, worth preserving

* * *

The Madness of Art —Joyce Carol Oates (1994)

[....] In literature, the canonization of "classics" has resulted in the relative demotion of other writers and other kinds of writing; the elevation of "mainstream" and predominantly "realistic" writing has created a false topology in which numerous genres are perceived as inferior to, or at least significantly different from, the mainstream. If Edgar Allan Poe were alive and writing today, he would very likely not be accorded the acclaim given the putative "serious literary writer," but would be taxonomized as a "horror writer." Yet talent, not excluding genius, may flourish in any genre, provided it is not stigmatized by that deadly label "genre."

[....] this so-called genre fascinates me because it is so powerful a vehicle of truth-telling, and because there is no wilder region for the exercise of the pure imagination.

[....] The Gothic work resembles the tragic in that it is willing to confront mankind's—and nature's—darkest secrets. Its metaphysics is Plato's, and not Aristotle's. There is a profound difference between what appears to be, and what is; and if you believe otherwise, the Gothicist has a surprise for you. The strained, sunny smile of the Enlightenment—"All that is, is holy;" "Man is a rational being"—is confronted by the Gothicist, who, quite frankly, considering the history and prehistory of our species, knows better.

[....] the homogenization of culture, in which a single vision—democratic, Christian, liberal, "good"—has come to be identified with America generally.

[....] If there is any problem with the Gothic as an art, it is likely to lie in the quality of execution.

[....] To Lovecraft, too, "phenomena" rather than "persons" are the logical heroes of stories, one consequence of which is two-dimensional, stereotypical characters about whom it is difficult to care.

[....] Gothic fiction is the freedom of the imagination, the triumph of the unconscious. Its radical premise is that, out of utterly plausible and psychologically realistic situations, profound and intransigent truths will emerge. And it is entertaining; it is unashamed to be entertaining.

[....] We write in order not just to be read, but to read—texts not yet written, which only we can bring into being. Is this quest quixotic, perverse, or utterly natural? Normal? Do we have any choice? Henry James, one of our exemplary beings who understood the lure of the grotesque, the skull beneath the smiling face, as well as any writer, has characterized us all in these words: "We work in the dark—we do what we can—we give what we have. Our doubt is our passion, and our passion is our task. The rest is the madness of art."

* * *

What You Are Meant to Know: Twenty-One Horror Classics —Robert Weinberg (1996)

[....] The biggest problem faced by many new writers is not lack of skills.... There is one area of their education that has been sorely neglected. They don't know much about their subject. It's difficult—nearly impossible, actually—to be original if you do not know what else has been written.

[....] 1. Frankenstein by Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley

[....] 2. Dracula by Bram Stoker

[....] 3. The Ghost Pirates by William Hope Hodgson

[....] The Ghost Pirates.... tells in straightforward, almost journalistic manner how a ship is overwhelmed by ghostly invaders. Hodgson makes no effort to identify the menacing figures—they could be the ghosts of dead pirates or beings from another dimension. All that

counts is their gradual capture of the boat. It is one of the finest examples of the "tightly written" novel ever published.

[....] 4. The Collected Ghost Stories of M.R. James

[....] 5. Burn, Witch, Burn! by A. Merritt

[....] Merritt wrote several novels that crossed over into the horror field. Of these, Burn, Witch, Burn! was the most successful and important. It deals with an evil crone who turns people into demonic dolls to commit crimes for her. What raises the book above standard pulp fare is that the witch's nemesis is a crime kingpin, a typical gangster of the 1930s, and his band of hoodlums. In an interesting reversal, a lesser evil battles a greater evil as the modern world fights a menace from ancient times....

[....] 6. To Walk the Night by William Sloane

[....] In the 1930s, genre fiction was not so clearly defined and writers were more willing to bend the rules for the sake of a good story.

[....] Sloane's To Walk the Night.... combines horror, science fiction, and mystery into one of the smoothest presentations ever set on paper.

[....] 7. The Dunwich Horror and Others by H.P. Lovecraft

[....] Lovecraft had his weaknesses (lack of characterization and dialogue are the worst), but his talent at hinting at the monstrous horrors lurking in the dark corners of our world remains unmatched more than a half century after his death.

[....] 9. Darker Than You Think by Jack Williamson

[....] remains the definitive werewolf novel.

[....] 10. Conjure Wife by Fritz Leiber

[....] 11. I Am Legend by Richard Matheson

[....] 12. Rosemary's Baby by Ira Levin

[....] 13. Richard Matheson: Collected Stories, Vols. I, II, III

[....] 14. Hell House by Richard Matheson

[....]15. The October Country by Ray Bradbury

[....] 16. Something Wicked This Way Comes by Ray Bradbury

[....] 17. The Exorcist by William Peter Blatty

[....] 18. Falling Angel by William Hjortsberg

[....] 19. Salem's Lot by Stephen King

[....] 20. The Stand by Stephen King

[....] 21. Watchers by Dean Koontz

[....] Tough, competent heroes and heroines engage in life-or-death struggles with sinister forces—from secret government agencies to science gone berserk—in a mad scramble....

* * *

Avoiding What's Been Done to Death —Ramsey Campbell (1987)

[....] You can't avoid anything unless you know what it is.

[....] The finest single introduction to it is Great Tales of Terror and the Supernatural , edited by Wise and Fraser....

[....] many of the themes we're dealing with are so large and powerful as to be essentially timeless.

[....] one way to avoid what has already been done is to be true to yourself.

[....] No writer has orchestrated terror in prose more carefully than Lovecraft, but you certainly won't learn how to write dialogue or deal with character from him. Such skills are best learned by reading writers outside the field (in my case, Nabokov and Graham Greene, among others).

[....] It's no bad thing to follow the example of writers you admire, then, but only as a means to finding your own voice. You won't find that, of course, unless you have something of your own to say.

[....] I tried (and still do try) to take nothing on trust to describe things as they really are or would be.

[....] the horror field is riddled with clichés.

[....] I think there are more fundamental clichés in the field, and I think today's writers may be the ones to overturn them.

[....] evil.... Writing about evil is a moral act, and it won't do to recycle definitions of evil—to take them on trust.

[....] If we're going to write about evil, then let's define it and how it relates to ourselves.

[....] good fiction consists of looking at things afresh, but horror fiction seems to have a built-in tendency to do the opposite.

[....] it's the job of writers to imagine how it would feel to be all their characters, however painful that may sometimes be.

[....] if you feel the need to write about the stock figures of the horror story, that's all the more reason to imagine them anew.

[....] many readers and publishers would rather see imitations of whatever they liked last year than give new ideas a chance.

[....] tradition is a pretty poor excuse for perpetuating stereotypes

[....] time-honored it may be, but that certainly doesn't make it honorable. In fact, these days, so many horror stories (and especially films) gloat over the suffering of women that it seems clear the authors are getting their own back, consciously or not, on aspects of real life that they can't cope with.

[....] I have my suspicions, too, about the argument that horror fiction defines what is normal by showing us what isn't.

[....] it's time for more of the field to acknowledge that, when we come face-to-face with the monsters, we may find ourselves looking not at a mask but at a mirror.

* * *

Going There: Strategies for Writing the Things That Scare You —Michael Marano (2005)

[....] Giving a strategic glimpse of what frightens you can lessen the effect of writing about that thing 's impact on you, and it can, at the same time, increase the impact of that thing (whatever it is) on your readers.

[....] It's a given in horror that the unknown is a great source of fear. But what's known, in the right context, can be much worse.

* * *

Darkness Absolute: The Standards of Excellence in Horror Fiction —Douglas E. Winter (1987)

[....] What makes great horror fiction?

[....] What follows.... is a series of principles intended to offer general guidelines to the developing writer. As generalizations, they are subject to inevitable exceptions, and they must not, under any circumstances, be considered hard-and-fast rules.

[....] Originality

[....] most horror writers are, first and foremost, horror fans. Their stories naturally tend to emulate, in style and subject, the film or fiction that they like best. There are, then, hundreds of published and unpublished books that read like rote imitations of best-selling novels or popular films, replete with such well-worn icons as Indian burial grounds, small towns besieged by evil, and ghastly presences that are revealed.

[....] Imitation is a time-honored method of learning the fundamentals of writing

[....] you will risk learning your craft at the feet of mediocrity.

[....] the task of finding your own voice will be eased if you stop reading what the marketplace calls horror fiction and join me in an important bit of heresy: Horror is not a genre. It is an emotion.

[....] Characterization

[....] horror, as an emotion, is measured by its context—its time, its place, its characters.

[....]we care about the outcome of a story only if we have some emotional stake in its context.

[....] "You have got to love the [characters]"

[....] stories do not proceed from events, but from the perception of events.

[....] acts and words of its characters should.... be colored by their personalities.

[....] Reality

[....] no effective horror without a context of normality.

[....] best horror fiction effectively counterfeits reality, placing the reader firmly within the worldly, even as it invokes the otherworldly.

[....] For this reason, Richard Matheson is the most influential horror writer of this generation.

[....] Embrace the ordinary so that the extraordinary events depicted will be heightened when played out against its context.

[....] Eschew exotic locales and the lifestyles of the rich and famous.... in favor of all that is mundane in your world.

[....] Mystery

[....] The workaday world is indeed mundane.... But it is a world whose ultimate meaning is shrouded by unanswered and unanswerable questions. Where did we come from? Where are we going when we die? Does evil exist beyond the mind of man?

[....] today, explanation, whether supernatural or rational, is simply not the business of horror fiction.

[....] One source of horror's popularity is that its questions are unanswerable. At its heart is a single certainty—that, in Hamlet's words, "all that live must die"—and a single question: What then?

[....] What we are looking for is a way to confess our doubts, our disbeliefs, our fears.

[....] Bad Taste

[....] most conventional horror stories proceed from the archetype of Pandora's box: the tense conflict between pleasure and fear that is latent when we face the forbidden and the unknown. In horror's pages, we open "the box," exposing what is taboo in our ordinary lives and witnessing both its dangers and its possibilities.

[....] A horror writer should be prepared not only to indulge in bad taste, but also to grapple with the taboo, dragging our terrors from the shadows and forcing readers to look upon them and despair—or laugh with relief.

[....] The writer must know when the boundary has been reached, and when he is stepping over the line into the no-man's land of taboo.

[....]Suggestion

[....] few writers seem to recognize that such explicitness is often anathema to horror.

[....] there is a more fundamental objection to explicitness. Too many purveyors of the "gross-out" are working from the proposition that the purpose of horror fiction is to shock the reader into submission.

[....] Great horror fiction is rarely about shock, but rather more lasting emotions. It digs beneath our skin and stays with us. It is proof that an image is only as powerful as its context.

[....] not only to scare, but also to disturb a reader, to invoke a memory that will linger long after the pages of the book are closed—is the true goal of every writer of horror fiction.

[....] Subtext

[....] D. H. Lawrence wrote of Edgar Allan Poe's horror fiction: "It is lurid and melodramatic, but it is true." Great horror fiction provides the shocks, the scares, all the entertainments of the carnival funhouse; but it also offers something more: a lasting impression, one both disturbing and oddly uplifting.

[....] is also the means by which the traditional imagery of horror may be reenacted, updated, elevated.

[....] Subversion

[....] The best horror fiction is intrinsically subversive, striking against the pasteboard masks of fantasy to seek the true face of reality.

[....] great horror fiction being written today runs consistently against the grain of conventional horror, as if intent on forging something that might well be called the antihorror story.

[....] The bogeymen of the Halloween and Friday the 13th films are the hitmen of homogeneity. Don't do it, they tell us, or you will pay an awful price. Don't talk to strangers.... Don't party. Don't make love. Don't dare to be different.

[....] it is proper behavior, not crucifixes or silver bullets, that tends to ward off the monsters of our times.

[....] antihorror story tells us that conformity is the ultimate horror—and that monsters are, perhaps, passé.

[....] Monsters

[....] the great horror fiction being written today is rarely about monsters.

[....] The vampire is an anachronism in the wake of the sexual revolution. The bite of Bram Stoker's Dracula (1897), sharpened in the repression of Victorian times, has been blunted by the likes of Dr. Ruth Westheimer.

[....] The werewolf will live so long as we struggle with the beast within, but its modern incarnations, from Whitley Strieber's The Wolfen (1979) and Thomas Tessier's The Nightwalker (1979), suggest that the savage has already won and is loose on the streets of the urban jungle.

[....] Endgame

[....] Ending a horror story, particularly one of novel length, is probably the writer's greatest challenge.

[....] We know, if only implicitly, that consummate evil cannot be overcome, cast out of our world completely.

[....] We also know that the good in this world is not free—that there must be payout as well as payback .

* * *

Jay

25 November 2022