"You are still under his spell," she cried, anxiously.

A little shaken in his confidence, Ernest resumed: "Reginald is utterly incapable of such an action, even granting that he possessed the terrible power of which you speak. A man of his splendid resources, a literary Midas at whose very touch every word turns into gold, is under no necessity to prey on the thoughts of others. Circumstances, I admit, are suspicious. But in the light of common day this fanciful theory shrivels into nothing. Any court of law would reject our evidence as madness. It is too utterly fantastic, utterly alien to any human experience."

"Is it though?" Ethel replied with peculiar intonation.

"Why, what do you mean?"

"Surely," she answered, "you must know that in the legends of every nation we read of men and women who were called vampires. They are beings, not always wholly evil, whom every night some mysterious impulse leads to steal into unguarded bedchambers, to suck the blood of the sleepers and then, having waxed strong on the life of their victims, cautiously to retreat. Thence comes it that their lips are very red. It is even said that they can find no rest in the grave, but return to their former haunts long after they are believed to be dead. Those whom they visit, however, pine away for no apparent reason. The physicians shake their wise heads and speak of consumption. But sometimes, ancient chronicles assure us, the people's suspicions were aroused, and under the leadership of a good priest they went in solemn procession to the graves of the persons suspected. And on opening the tombs it was found that their coffins had rotted away and the flowers in their hair were black. But their bodies were white and whole; through no empty sockets crept the vermin, and their sucking lips were still moist with a little blood."

Ernest was carried away in spite of himself by her account, which vividly resembled his own experience. Still he would not give in.

Reginald Clarke sups on the artistic powers found in talented young men and women. He absorbs their skills and leaves them raped and gibbering ruins.

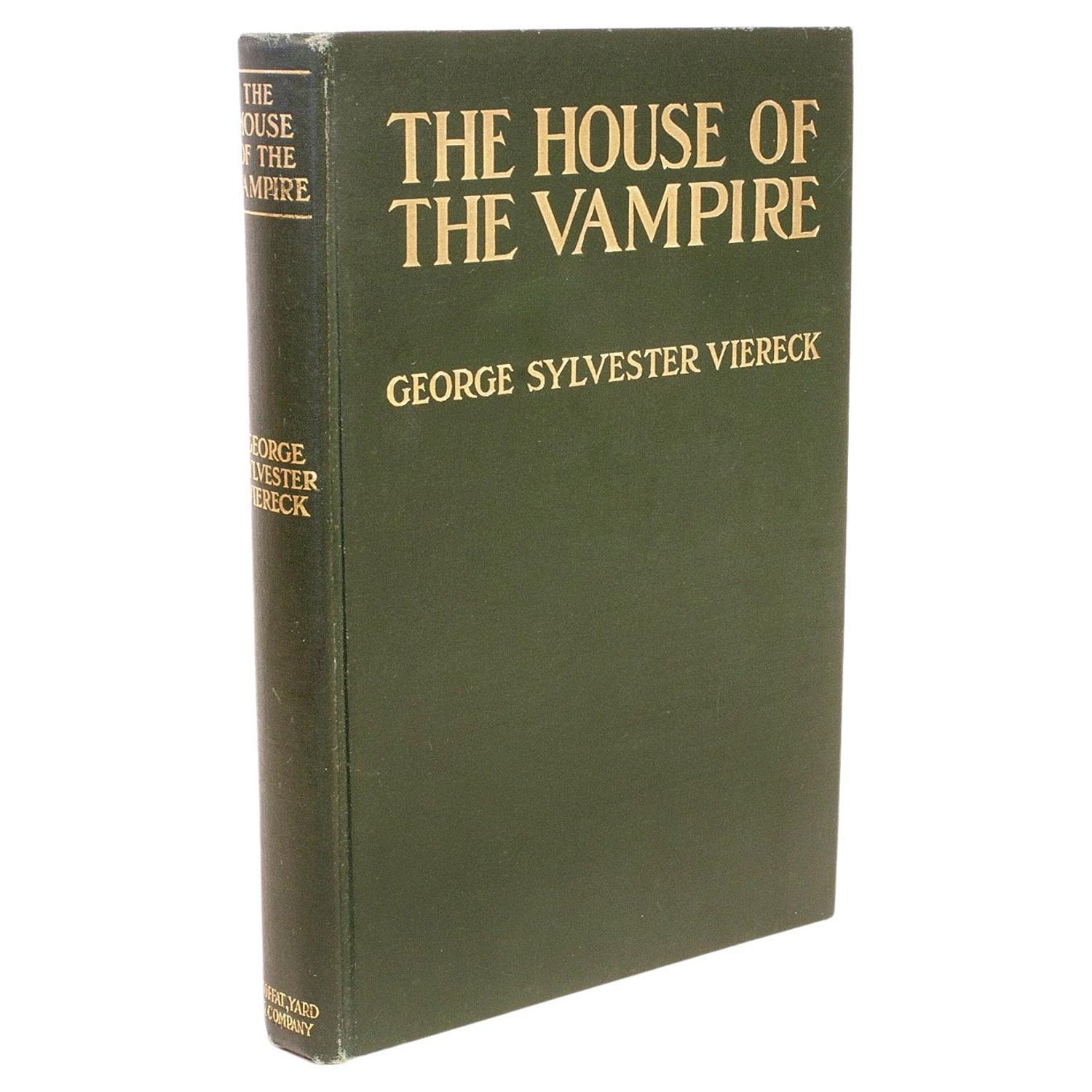

The House of the Vampire by George Sylvester Viereck (1907) is a story about Reginald facing the consequences of this course, and the animus of two victims.

In tone it begins as a decadent novel detailing nonchalant "healthy young animals bred in the atmosphere of an American college," and what results when they meet an adult world red in tooth and claw.

From Chapter 5:

"Do you mean, then, that a subtle psychologist ought to be able to read beneath and between our lines, not only what we express, but also what we leave unexpressed?"

"Undoubtedly."

"Even if, while we are writing, we are unconscious of our state of mind? That would open a new field to psychology."

"Only to those that have the key, that can read the hidden symbols. It is to me a matter-of-course that every mind-movement below or above the threshold of consciousness must, of a necessity, leave its imprint faintly or clearly, as the case may be, upon our activities."

"This may explain why books that seem intolerably dull to the majority, delight the hearts of the few," Ernest interjected.

"Yes, to the few that possess the key. I distinctly remember how an uncle of mine once laid down a discussion on higher mathematics and blushed fearfully when his innocent wife looked over his shoulder. The man who had written it was a roué."

"Then the seemingly most harmless books may secretly possess the power of scattering in young minds the seed of corruption," Walkham remarked.

"If they happen to understand," Clarke observed thoughtfully. "I can very well conceive of a lecherous text-book of the calculus, or of a reporter's story of a picnic in which burnt, under the surface, undiscoverable, save to the initiate, the tragic passion of Tristram and Iseult."

Gifted young poet Ernest Fielding falls under the influence of Reginald Clarke. This seduction and subordination alarms an older woman who loves Fielding. Painter Ethel Brandenbourg knows the costs of life with Reginald because she is Reginald's drained and discarded ex-wife.

From Chapters 20 and 21:

XX

They were sitting in a little Italian restaurant where they had often, in the old days, lingered late into the night over a glass of Lacrimæ Christi. But no pale ghost of the past rose from the wine. Only a wriggling something, with serpent eyes, that sent cold shivers down her spine and held her speechless and entranced.

When their order had been filled and the waiter had posted himself at a respectful distance, Reginald began—at first leisurely, a man of the world. But as he proceeded a strange exultation seemed to possess him and from his eyes leaped the flame of the mystic.

"You must pardon me," he commenced, "if I monopolise the conversation, but the revelations I have to make are of such a nature that I may well claim your attention. I will start with my earliest childhood. You remember the picture of me that was taken when I was five?"

She remembered, indeed. Each detail of his life was deeply engraven on her mind.

"At that time," he continued, "I was not held to be particularly bright. The reason was that my mind, being pre-eminently and extraordinarily receptive, needed a stimulus from without. The moment I was sent to school, however, a curious metamorphosis took place in me. I may say that I became at once the most brilliant boy in my class. You know that to this day I have always been the most striking figure in any circle in which I have ever moved."

Ethel nodded assent. Silently watching the speaker, she saw a gleam of the truth from afar, but still very distant and very dim.

Reginald lifted the glass against the light and gulped its contents. Then in a lower voice he recommenced: "Like the chameleon, I have the power of absorbing the colour of my environment."

"Do you mean that you have the power of absorbing the special virtues of other people?" she interjected.

"That is exactly what I mean."

"Oh!" she cried, for in a heart-beat many things had become clear to her. For the first time she realised, still vaguely but with increasing vividness, the hidden causes of her ruin and, still more plainly, the horrible danger of Ernest Fielding.

He noticed her agitation, and a look of psychological curiosity came into his eyes.

"Ah, but that is not all," he observed, smilingly. "That is nothing. We all possess that faculty in a degree. The secret of my strength is my ability to reject every element that is harmful or inessential to the completion of my self. This did not come to me easily, nor without a struggle. But now, looking back upon my life, many things become transparent that were obscure even to me at the time. I can now follow the fine-spun threads in the intricate web of my fate, and discover in the wilderness of meshes a design, awful and grandly planned."

His voice shook with conviction, as he uttered these words. There was something strangely gruesome in this man. It was thus that she had pictured to herself the high-priest of some terrible and mysterious religion, demanding a human sacrifice to appease the hunger of his god. She was fascinated by the spell of his personality, and listened with a feeling not far removed from awe. But Reginald suddenly changed his tone and proceeded in a more conversational manner.

"The first friend I ever cared for was a boy marvellously endowed for the study of mathematics. At the time of our first meeting at school, I was unable to solve even the simplest algebraical problem. But we had been together only for half a month, when we exchanged parts. It was I who was the mathematical genius now, whereas he became hopelessly dull and stuttered through his recitations only with a struggle that brought the tears to his eyes. Then I discarded him. Heartless, you say? I have come to know better. Have you ever tasted a bottle of wine that had been uncorked for a long time? If you have, you have probably found it flat—the essence was gone, evaporated. Thus it is when we care for people. Probably—no, assuredly—there is some principle prisoned in their souls, or in the windings of their brains, which, when escaped, leaves them insipid, unprofitable and devoid of interest to us. Sometimes this essence—not necessarily the finest element in a man's or a woman's nature, but soul-stuff that we lack—disappears. In fact, it invariably disappears. It may be that it has been transformed in the processes of their growth; it may also be that it has utterly vanished by some inadvertence, or that we ourselves have absorbed it."

"Then we throw them away?" Ethel asked, pale, but dry-eyed. A shudder passed through her body and she clinched her glass nervously. At that moment Reginald resembled a veritable Prince of Darkness, sinister and beautiful, painted by the hand of a modern master. Then, for a space, he again became the man of the world. Smiling and self-possessed, he filled the glasses, took a long sip of the wine and resumed his narrative.

"That boy was followed by others. I absorbed many useless things and some that were evil. I realised that I must direct my absorptive propensities. This I did. I selected, selected well. And all the time the terrible power of which I was only half conscious grew within me."

"It is indeed a terrible power," she cried; "all the more terrible for its subtlety. Had I not myself been its victim, I should not now find it possible to believe in it."

"The invisible hand that smites in the dark is certainly more fearful than a visible foe. It is also more merciful. Think how much you would have suffered had you been conscious of your loss."

"Still it seems even now to me that it cannot have been an utter, irreparable loss. There is no action without reaction. Even I—even we—must have received from you some compensation for what you have taken away."

"In the ordinary processes of life the law of action and reaction is indeed potent. But no law is without exception. Think of radium, for instance, with its constant and seemingly inexhaustible outflow of energy. It is a difficult thing to imagine, but our scientific men have accepted it as a fact. Why should we find it more difficult to conceive of a tremendous and infinite absorptive element? I feel sure that it must somewhere exist. But every phenomenon in the physical world finds its counterpart in the psychical universe. There are radium-souls that radiate without loss of energy, but also without increase. And there are souls, the reverse of radium, with unlimited absorptive capacities."

"Vampire-souls," she observed, with a shudder, and her face blanched.

"No," he said, "don't say that." And then he suddenly seemed to grow in stature. His face was ablaze, like the face of a god.

"In every age," he replied, with solemnity, "there are giants who attain to a greatness which by natural growth no men could ever have reached. But in their youth a vision came to them, which they set out to seek. They take the stones of fancy to build them a palace in the kingdom of truth, projecting into reality dreams, monstrous and impossible. Often they fail and, tumbling from their airy heights, end a quixotic career. Some succeed. They are the chosen. Carpenter's sons they are, who have laid down the Law of a World for milleniums to come; or simple Corsicans, before whose eagle eye have quaked the kingdoms of the earth. But to accomplish their mission they need a will of iron and the wit of a hundred men. And from the iron they take the strength, and from a hundred men's brains they absorb their wisdom. Divine missionaries, they appear in all departments of life. In their hand is gathered to-day the gold of the world. Mighty potentates of peace and war, they unlock new seas and from distant continents lift the bars. Single-handed, they accomplish what nations dared not hope; with Titan strides they scale the stars and succeed where millions fail. In art they live, the makers of new periods, the dreamers of new styles. They make themselves the vocal sun-glasses of God. Homer and Shakespeare, Hugo and Balzac—they concentrate the dispersed rays of a thousand lesser luminaries in one singing flame that, like a giant torch, lights up humanity's path."

She gazed at him, open-mouthed. The light had gone from his visage. He paused, exhausted, but even then he looked the incarnation of a force no less terrible, no less grand. She grasped the immensity of his conception, but her woman's soul rebelled at the horrible injustice to those whose light is extinguished, as hers had been, to feed an alien flame. And then, for a moment, she saw the pale face of Ernest staring at her out of the wine.

"Cruel," she sobbed, "how cruel!"

"What matter?" he asked. "Their strength is taken from them, but the spirit of humanity, as embodied in us, triumphantly marches on."

XXI

Reginald's revelations were followed by a long silence, interrupted only by the officiousness of the waiter. The spell once broken, they exchanged a number of more or less irrelevant observations. Ethel's mind returned, again and again, to the word he had not spoken. He had said nothing of the immediate bearing of his monstrous power upon her own life and that of Ernest Fielding.

At last, somewhat timidly, she approached the subject.

"You said you loved me," she remarked.

"I did."

"But why, then—"

"I could not help it."

"Did you ever make the slightest attempt?"

"In the horrible night hours I struggled against it. I even implored you to leave me."

"Ah, but I loved you!"

"You would not be warned, you would not listen. You stayed with me, and slowly, surely, the creative urge went out of your life."

"But what on earth could you find in my poor art to attract you? What were my pictures to you?"

"I needed them, I needed you. It was a certain something, a rich colour effect, perhaps. And then, under your very eyes, the colour that vanished from your canvases reappeared in my prose. My style became more luxurious than it had been, while you tortured your soul in the vain attempt of calling back to your brush what was irretrievably lost."

"Why did you not tell me?"

"You would have laughed in my face, and I could not have endured your laugh. Besides, I always hoped, until it was too late, that I might yet check the mysterious power within me. Soon, however, I became aware that it was beyond my control. The unknown god, whose instrument I am, had wisely made it stronger than me."

"But why," retorted Ethel, "was it necessary to discard me, like a cast-off garment, like a wanton who has lost the power to please?"

Her frame shook with the remembered emotion of that moment, when years ago he had politely told her that she was nothing to him.

"The law of being," Reginald replied, almost sadly, "the law of my being. I should have pitied you, but the eternal reproach of your suffering only provoked my anger. I cared less for you every day, and when I had absorbed all of you that my growth required, you were to me as one dead, as a stranger you were. There was between us no further community of interest; henceforth, I knew, our lives must move in totally different spheres. You remember that day when we said good-bye?"

Ernest Fielding is convinced by Ethel's arguments. At night he feels Reginald pawing through his mind for aesthetic treasures. He vows to stand up to Reginald, at terrible risk, in hopes of saving himself.

* * *

The House of the Vampire deals with both psychic (emotional) vampirism as metaphor, and as actual physical practice. Author George Sylvester Viereck handles his material deftly. This is a story of real emotional power.

Jay

16 April 2022

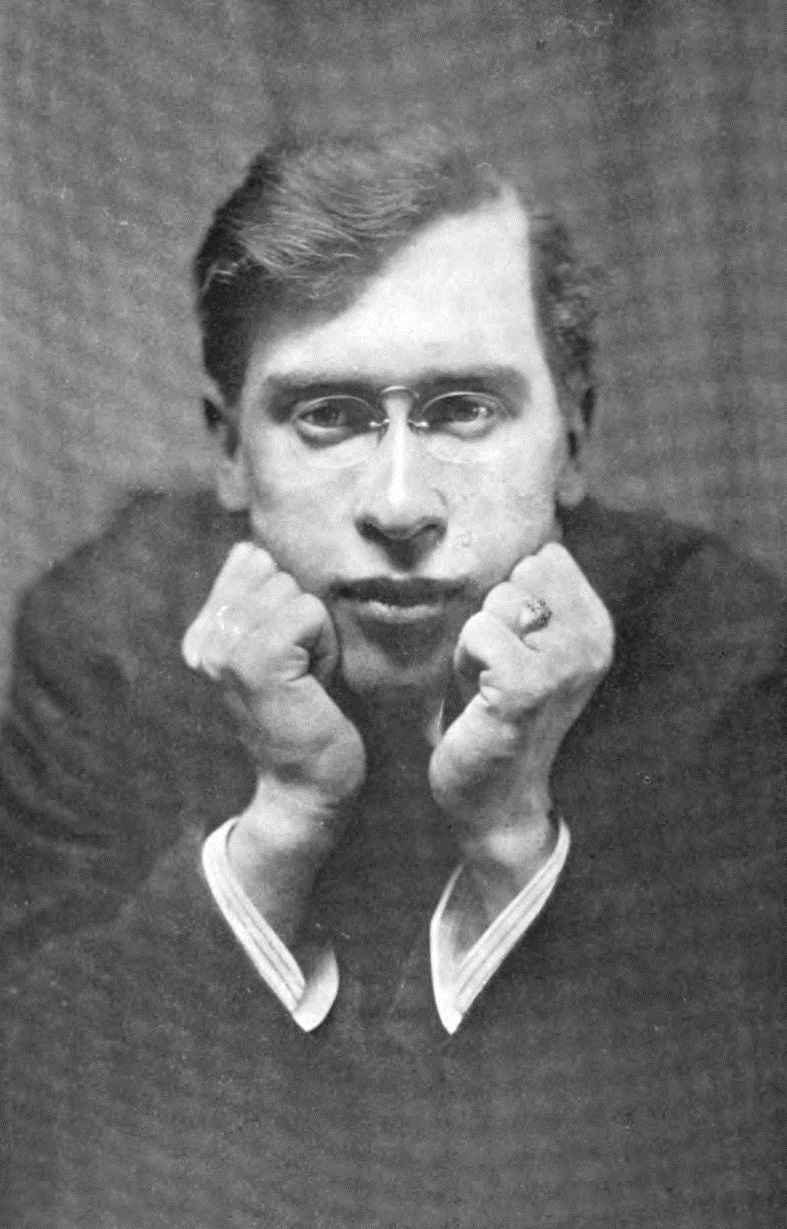

George Sylvester Viereck (1884-1962)