"If Mr. Hyde had sired a son," said Lord Terry, "do you realize that the loathsome child could be alive at this moment?"

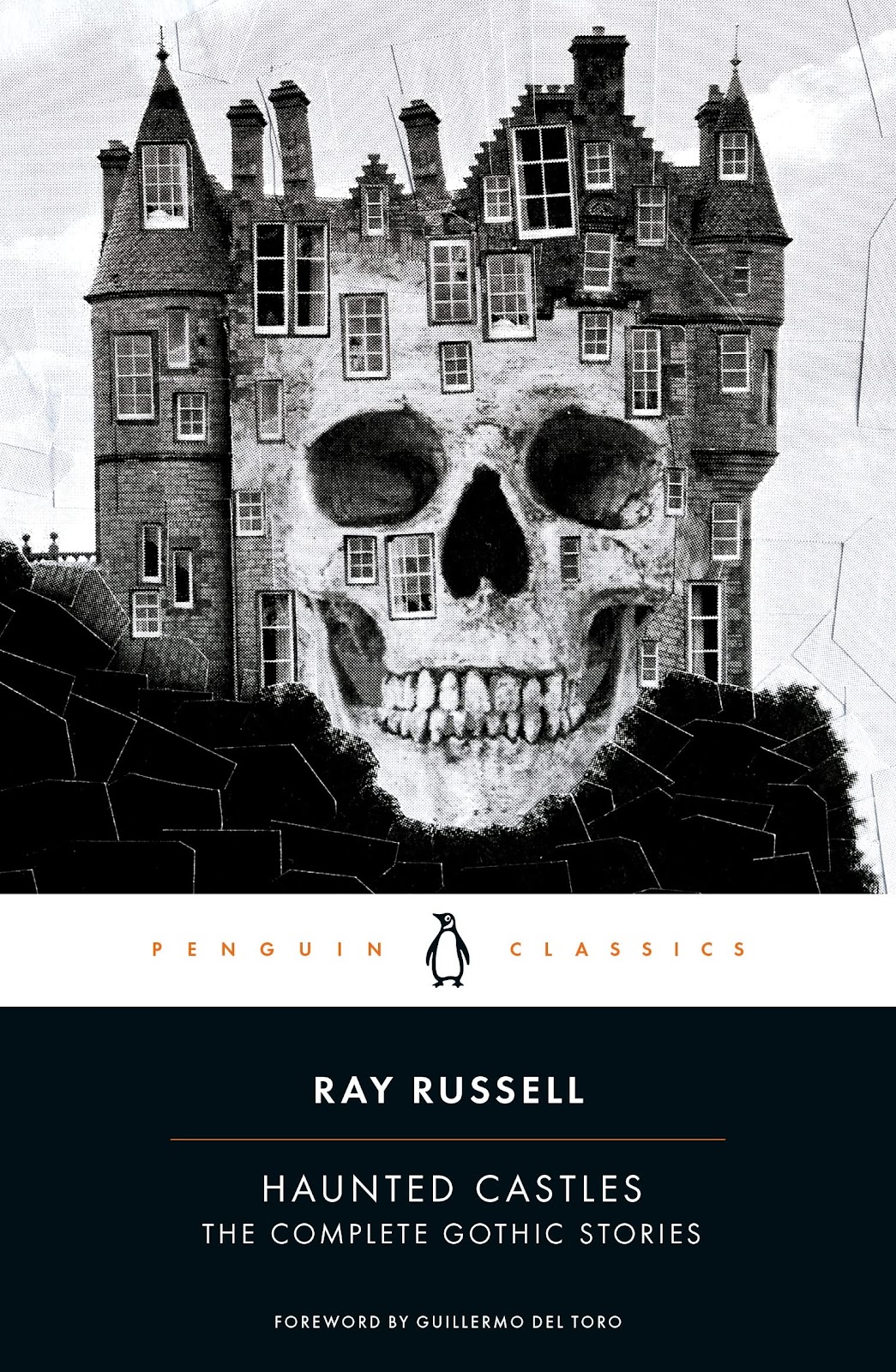

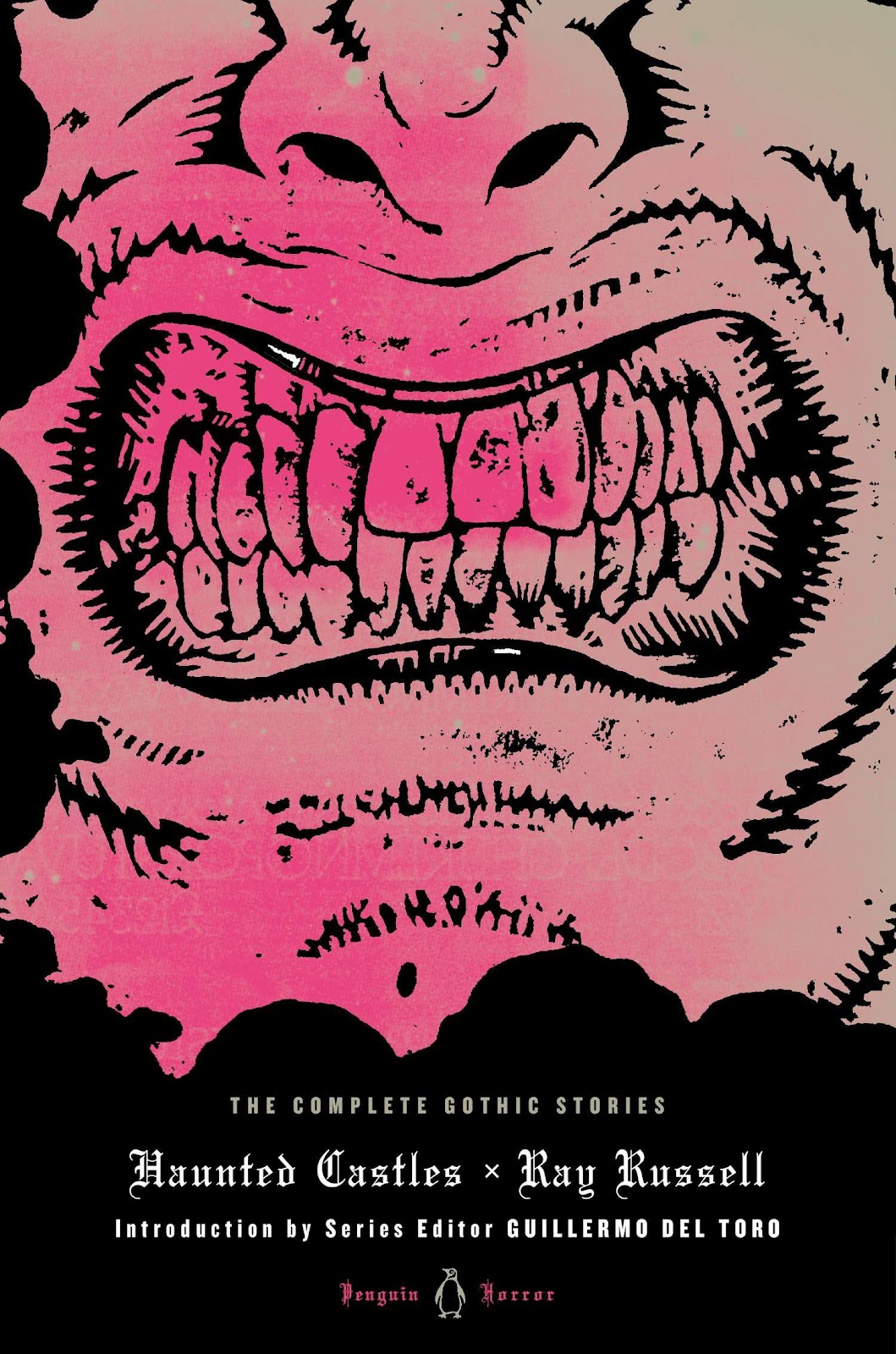

"Sagittarius" (1962) from Haunted Castles: The Complete Gothic Tales of Ray Russell (1985)

* * *

"Sagittarius" is for me the most satisfying of Ray Russell's trilogy of "S" faux-Gothic novellas. Third-person point of view that also imbricates extended first-person narration was clearly a salutary choice of approach.

"Sagittarius" is a club story, told in an Anglophile NYC gentlemen's club by an English lord to a U.S. (?) theater historian.

Though of different ages, Lord Terry and Rolfe Hunt appear deeply simpatico. Russell excels in his opening here, as the two men discuss the possibility that Stevenson's Edward Hyde character might have been "drawn from life" and sired a son.

....It was a humid summer evening, but he and his guest, Rolfe Hunt, were cool and crisp. They were sitting in the quiet sanctuary of the Century Club (so named, say wags, because its members all appear to be close to that age) and, over their drinks, had been talking about vampires and related monsters, about ghost stories and other dark tales of happenings real and imagined, and had been recounting some of their favorites. Hunt had been drinking martinis, but Lord Terry—The Earl Terrence Glencannon, rather—was a courtly old gentleman who considered the martini one of the major barbarities of the Twentieth Century. He would take only the finest, driest sherry before dinner, and he was now sipping his third glass. The conversation had touched upon the series of mutilation-killings that were currently shocking the city, and then upon such classic mutilators as Bluebeard and Jack the Ripper, and then upon murder and evil in general; upon certain works of fiction, such as The Turn of the Screw and its alleged ambiguities, Dracula, the short play A Night at an Inn, the German silent film Nosferatu, some stories of Blackwood, Coppard, Machen, Montague James, Le Fanu, Poe, and finally upon The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, which had led the Earl to make his remark about Hyde's hypothetical son....

* * *

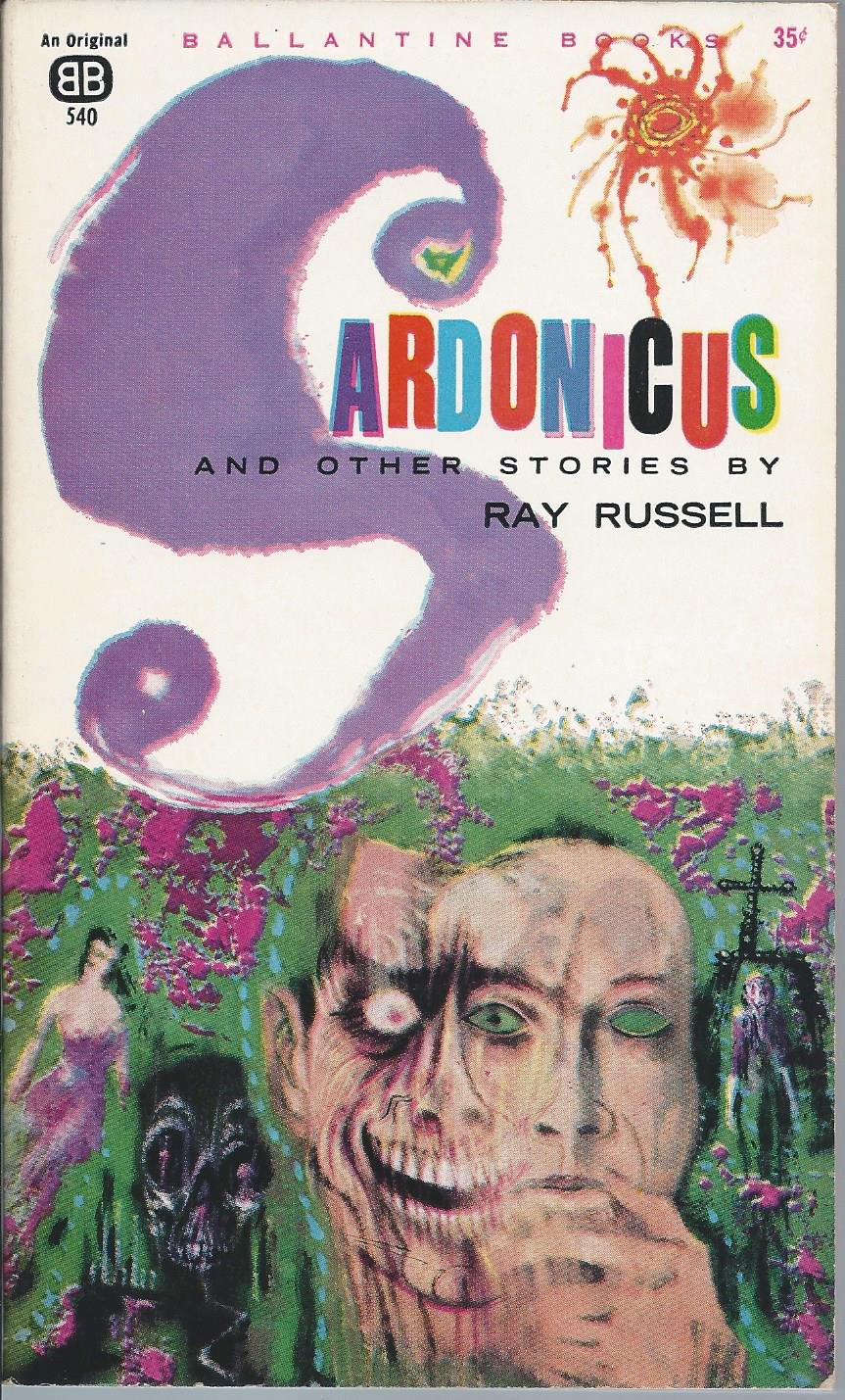

"Sagittarius" excels "Sardonicus" in control and execution. "Sardonicus" is gothic recrudescence at play with old cliches. "Sagittarius" strikes the first-time reader as an ambitious reinvigoration of tradition. For anyone who values skillful storytelling, it is a pleasure to read and to master.

After its clubland opening, "Sagittarius" begins again: Lord Harry relates a youthful adventure in the theater world of fin de siècle Paris, and his encounters with an actor named Sébastien Sellig, a man now lost to history.

He was appearing at the Théâtre Français, in Racine's Britannicus. He played the young Nero. And he played him with such style and fervor and godlike grace that one could feel the audience's sympathies being drawn toward Nero as to a magnet. I saw him afterward, in his dressing room, where he was removing his make-up. César introduced us.

He was a man of surpassing beauty: a face like the Apollo Belvedere, with classic features, a tumble of black curls, large brown eyes, and sensuous lips. I did not compliment him on his good looks, of course, for the world had only recently become unsafe for even the most innocent admiration between men, Oscar Wilde having died in Paris just nine years before. I did compliment him on his performance, and on the rush of sympathy which I've already remarked.

"Thank you," he said, in English, which he spoke very well. "It was unfortunate."

"Unfortunate?"

"The audience's sympathies should have remained with Britannicus. By drawing them to myself—quite inadvertently, I assure you—I upset the balance, reversed Racine's intentions, and thoroughly destroyed the play."

"But," observed César lightly, "you achieved a personal triumph."

"Yes," said Sellig. "At irreparable cost. It will not happen again, dear César, you may be sure of that. Next time I play Nero, I shall do so without violating Racine."

César, being a professional, took exception. "You can't be blamed for your charm, Sébastien," he insisted.

Sellig wiped off the last streak of paint from his face and began to draw on his street clothes. "An actor who cannot control his charm," he said, "is like an actor who cannot control his voice or his limbs. He is worthless." Then he smiled, charmingly. "But we mustn't talk shop in front of your friend. So very rude. Come, I shall take you to an enchanting little place for supper."

It was a small, dark place called L'Oubliette. The three of us ate an enormous and very good omelette, with crusty bread and a bottle of white wine. Sellig talked of the differences between France's classic poetic dramatist, Racine, and England's, Shakespeare. "Racine is like"—he lifted the bottle and refilled our glasses—"well, he is like a very fine vintage white. Delicate, serene, cool, subtle. So subtle that the excellence is not immediately enjoyed by uninitiated palates. Time is required, familiarity, a return and another return and yet another."

As an Englishman, I was prepared to defend our bard, so I asked, a little belligerently: "And Shakespeare?"

"Ah, Shakespeare!" smiled Sellig. "Passionel, tumultueux! He is like a mulled red, hot and bubbling from the fire, dark and rich with biting spices and sweet honey! The senses are smitten, one is overwhelmed, one becomes drunk, one reels, one spins . . . it can be a most agreeable sensation."

He drank from his glass. "Think of tonight's play. It depicts the first atrocity in a life of atrocities. It ends as Nero murders his brother. Later, he was to murder his mother, two wives, a trusted tutor, close friends, and untold thousands of Christians who died horribly in his arenas. But we see none of this. If Shakespeare had written the play, it would have begun with the death of Britannicus. It would then have shown us each new outrage, the entire chronicle of Nero's decline and fall and ignoble end. Enfin, it would have been Macbeth."

I had heard of a little club where the girls danced in shockingly indecorous costumes, and I was eager to go. César allowed himself to be persuaded to take me there, and I invited Sellig to accompany us. He declined, pleading fatigue and a heavy day ahead of him. "Then perhaps," I said, "you will come with us tomorrow evening? It may not tempt a gentleman of your lofty theatrical tastes, but I'm determined to see a show at this Grand Guignol which César has told me of. Quite bloody and outrageous, I understand—rather like Shakespeare." Sellig laughed at my little joke. "Will you come? Or perhaps you have a performance . . ."

"I do have a performance," he said, "so I cannot join you until later. Suppose we plan to meet there, in the foyer, directly after the last curtain?"

"Will you be there in time?" I asked. "The Guignol shows are short, I hear."

"I will be there," said Sellig, and we parted.

Fascinated by Sellig's thespian skill, Lord Harry almost simultaneously becomes obsessed with another performer at a more plebeian venue. (This is not the last doubling or twinning author Ray Russell will explore in "Sagittarius".)

….the evening following my first meeting with Sellig, César and I were seated in this unique little theatre with two young ladies we had escorted there; they were uncommonly pretty but uncommonly common—in point of fact, they were barely on the safe side of respectability's border, being inhabitants of that peculiar demimonde, that shadow world where several professions—actress, model, barmaid, bawd—mingle and merge and overlap and often coexist. But we were young, César and I, and this was, after all, Paris. Their names, they told us, were Clothilde and Mathilde—and I was never quite sure which was which. Soon after our arrival, the lights dimmed and the Guignol curtain was raised.

The first offering on the programme was a dull, shrill little boudoir farce that concerned itself with broken corset laces and men hiding under the bed and popping out of closets. It seemed to amuse our feminine companions well enough, but the applause in the house was desultory, I thought, a mere form . . . this fluttering nonsense was not what the patrons had come for, was not the sort of fare on which the Guignol had built its reputation. It was an hors d'oeuvre. The entrée followed:

It was called, if memory serves, La Septième Porte, and was nothing more than an opportunity for Bluebeard—played by an actor wearing an elaborately ugly make-up—to open six of his legendary seven doors for his new young wife (displaying, among other things, realistically mouldering cadavers and a torture chamber in full operation). Remaining faithful to the legend, Bluebeard warns his wife never to open the seventh door. Left alone on stage, she of course cannot resist the tug of curiosity—she opens the door, letting loose a shackled swarm of shrieking, livid, rag-bedecked but not entirely unattractive harpies, whose white bodies, through their shredded clothing, are crisscrossed with crimson welts. They tell her they are Bluebeard's ex-wives, kept perpetually in a pitch-dark dungeon, in a state near to starvation, and periodically tortured by the vilest means imaginable. Why? the new wife asks. Bluebeard enters, a black whip in his hand. For the sin of curiosity, he replies—they, like you, could not resist the lure of the seventh door! The other wives chain the girl to them, and cringing under the crack of Bluebeard's whip, they crawl back into the darkness of the dungeon. Bluebeard locks the seventh door and soliloquizes: Diogenes had an easy task, to find an honest man; but my travail is tenfold—for where is she, does she live, the wife who does not pry and snoop, who does not pilfer her husband's pockets, steam open his letters, and when he is late returning home, demand to know what wench he has been tumbling?

The lights had been dimming slowly until now only Bluebeard was illumined, and at this point he turned to the audience and addressed the women therein. "Mesdames et Mademoiselles!" he declaimed. "Écoute! En garde! Voici la septième porte—Hear me! Beware! Behold the seventh door!" By a stage trick the door was transformed into a mirror. The curtain fell to riotous applause.

Recounted baldly, La Septième Porte seems a trumpery entertainment, a mere excuse for scenes of horror—and so it was. But there was a strength, a power to the portrayal of Bluebeard; that ugly devil up there on the shabby little stage was like an icy flame, and when he'd turned to the house and delivered that closing line, there had been such force of personality, such demonic zeal, such hatred and scorn, such monumental threat, that I could feel my young companion shrink against me and shudder.

"Come, come, ma petite," I said, "it's only a play."

"Je le déteste," she said.

"You detest him? Who, Bluebeard?"

"Laval."

My French was sketchy at that time, and her English almost nonexistent, but as we made our slow way up the aisle, I managed to glean that the actor's name was Laval, and that she had at one time had some offstage congress with him, congress of an intimate nature, I gathered. I could not help asking why, since she disliked him so. (I was naïf then, you see, and knew little of women; it was somewhat later in life I learned that many of them find evil and even ugliness irresistible). In answer to my question, she only shrugged and delivered a platitude: "Les affaires sont les affaires—Business is business."

Sellig was waiting for us in the foyer. His height, and his great beauty of face, made him stand out. Our two pretty companions took to him at once, for his attractive exterior was supplemented by waves of charm.

"Did you enjoy the programme?" he asked of me.

I did not know exactly what to reply. "Enjoy? . . . Let us say I found it fascinating, M'sieu' Sellig."

"It did not strike you as tawdry? cheap? vulgar?"

"All those, yes. But at the same time, exciting, as sometimes only the tawdry, the cheap, the vulgar, can be."

"You may be right. I have not watched a Guignol production for several years. Although, surely, the acting . . ."

We were entering a carriage, all five of us. I said, "The acting was unbelievably bad—with one exception."

"Really? And the exception?"

"The actor who played Bluebeard in a piece called La Septième Porte. His name is—" I turned to my companion again.

"Laval," she said, and the sound became a viscous thing.

"Ah yes," said Sellig. "Laval. The name is not entirely unknown to me. Shall we go to Maxime's?"

We did, and experienced a most enjoyable evening. Sellig's fame and personal magnetism won us the best table and the most efficient service. He told a variety of amusing—but never coarse—anecdotes about theatrical life, and did so without committing that all-too-common actor's offense of dominating the conversation. One anecdote concerned the theatre we had just left:

"I suppose César has told the story of the Guignol doctor. No? Ah then, it seems that at one point it was thought a capital idea to hire a house physician—to tend to swooning patrons and so on, you know. This was done, but it was unsuccessful. On the first night of the physician's tour of duty, a male spectator found one particular bit of stage torture too much for him, and he fainted. The house physician was summoned. He could not be found. Finally, the ushers revived the unconscious man without benefit of medical assistance, and naturally they apologized profusely and explained they had not been able to find the doctor. 'I know,' the man said, rather sheepishly, 'I am the doctor.'"

At the end of the evening, César and I escorted our respective (but not precisely respectable) young ladies to their dwellings, where more pleasure was found. Sellig went home alone. I felt sorry for him, and there was a moment when it crossed my mind that perhaps he was one of those men who have no need of women—the theatrical profession is thickly inhabited by such men—but César privately assured me that Sellig had a mistress, a lovely and gracious widow named Lise, for Sellig's tastes were exceedingly refined and his image unblemished by descents into the dimly lit world of the sporting house. My own tastes, though acute, were not so elevated, and thus I enjoyed myself immensely that night.

Ignorance, they say, is bliss. I did not know that my ardent companion's warmth would turn unalterably cold in the space of a single night.

"Sagittarius" is an impeccable celebration of theatrical Paris, of assumed and hidden identities, and of the perils of pretense. It richly rewards careful reading and rereading.

Jay

15 April 2022