"Does anyone walk in the woods?"

"You won't see many. There's no paths, and if you aren't careful you'll think you've found one. It's not a place to walk on your own, but there's been a few who have."

"What happened to them?"

"Got lost and couldn't find their way out before dark. Had to stay there overnight and froze to death." He shook his head slowly and turned towards the stairs. "Unless you reckon they strayed in there after dark."

"What would have made them do that?"

"Just what I say," he responded as if she'd expressed more scepticism than in fact she had. "But to hear some of my dad's generation talk you'd think the forest was to blame, not these folk who go gallivanting when anyone with any sense wouldn't put their nose out of doors if they could help it. They're born that way if you ask me. If they aren't getting themselves stuck on the crags because they think they're Edmund Hillary, they're trying to prove they've more ice in their veins than the rest of us when it comes to the weather."

__

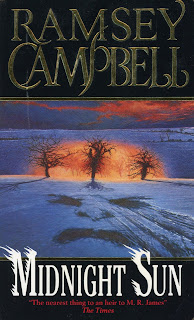

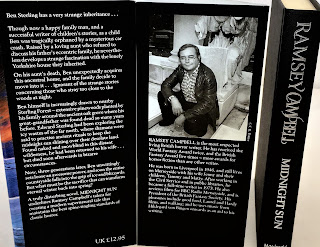

Midnight Sun by Ramsey Campbell (1990)

There are many ambitious horror writers, but few in the last hundred years with the skills and the commitment to write about the "horrors" we perceive in our confrontation with nature. Woods, open fields, mountains, rivers, oceans, and sky are different forces than spooks, possessions, psychotics, and beastly creatures, and it takes real artistic ambition to tackle them.

Feelings of uneasiness, awe, and menace inspired by measuring ourselves against Nature, the risks of self-forgetting involved in being isolated within its meshes, are beautifully articulated by Campbell in Midnight Sun.

Protagonist Ben Sterling brings his wife, son, and daughter back to the village where he was born and spent the first eight years of his life: Stargrave, in Yorkshire. (It is hard for me to imagine a more evocative place-name than Stargrave.) Ben and Ellen write and illustrate childrens books, and inheriting the property from Ben's aunt is a life-changing wind-fall.

Sterling Woods, which Campbell describes as being "above" Stargrave and the new house, is more than equal to Goodmanswood, the uncanny forest in The Darkest Part of the Woods. The more Ben explores the woods, alone and with his family, the more he senses something stirring in response. Soon Ellen, Johnny and Margaret start sensing it, too.

....Johnny avoided looking at it as he tramped across the crunchy grass to the trees.

The hovering mist steeped the forest in a twilight in which the tree trunks, which resembled scaly bones, appeared to glow. As soon as Johnny set foot on the path between them he saw his breath. He ran along the path, searching for trees he could shake to dislodge snow from them, trying to run far enough to be out of sight of his family and lie in wait for them. But the trees wouldn't shake; when he threw his weight against a trunk, that didn't bring down even so much as a snowflake. For a moment he thought the others had sneaked behind him, and then he saw them approaching on the path, his father's eyes gleaming in the forest twilight, Margaret rubbing her arms with her mittened hands. She looked ready to suggest going home out of the cold, and so Johnny shouted "Let's play hide and seek. Daddy can be It."

Their father went to the nearest marker post, which was painted with a blue arrow, and stared brightly at them before closing his eyes. "You'll be found, I promise," he said in a voice like a wind through the trees. "Off you go."

When Johnny saw that his sister was staying near the post he raced on tiptoe into the forest. By the time his father had counted thirty aloud, johnny had run far enough for the path and his family to be invisible for treetrunks. He darted behind two trees which grew very close together, and crouched to peer between them. He heard his father shout "Fifty" to announce that he'd finished counting, a shout which sounded tiny in the silence. Johnny crouched lower, waiting to catch sight of his father. He was still watching, and listening for movements in the hush which felt as if it was pinned down by all the trees, when he sensed that his father or Margaret had crept behind him.

No, not them. Their breath on his neck wouldn't be so cold, and even if both of them were standing there, their presence wouldn't feel so large. He swung round, sprawling on fallen needles. There was nobody to be seen, only trees like an enormous cage, but for an instant he felt as if whatever he'd sensed at his back had just hidden behind all of them at once. It had to have been the twilight, and the breath on his neck must have been a stray breeze. All the same, he was glad when he heard his father shout "I see you, Gretel" and Margaret's squeak of dismay, because then he was able to dash back to the marker post without fear of being made It.

When Margaret began to count he ran off the path. Though she was almost shouting, her voice immediately sounded even smaller than his father's had. Johnny dodged away from his father, who was also heading deeper into the forest, and hid in the midst of a circle of five close trees. He saw his father vanish among the trees to his left, and could just hear Margaret still counting, and so surely he was wrong to feel as if he wasn't alone in his hiding place. He glanced all around him, and then up. Of course, the mist was as close as the treetops to him. The pale blur above the branches laden with snow made him think of a patch of a face — a face so huge that he was seeing too little of it to distinguish any features. The thought of a face as wide as the forest and hovering just above it sent him fleeing towards the marker post as soon as he heard Margaret stop counting.

"I see Johnny," she called almost at once, and beat him to the marker, though without much enthusiasm. When he skidded onto the path, kicking needles across it, she said "I don't want to play any more."

Now that she'd admitted it, he didn't need to. When he shrugged so as not to seem too eager she called "Dad, we've finished playing."

Perhaps Daddy thought she was trying to trick him, because he made no sound. Was he stealing towards them or standing as still as the forest? "We aren't playing any more," they shouted more or less in chorus, but the silence seemed to cut off their shouts as soon as the sound reached the first trees. "He's going to scare us," Margaret wailed.

Johnny couldn't tell if he shivered then or if the forest did. For a moment he thought the trees had somehow drawn together, then that something had inched towards him and Margaret between far too many trees. He could hardly see beyond the nearest trees because of the fog of his breath. When a figure appeared to his right, between trees so distant they resembled a solid scaly wall, he wasn't sure that he wanted to see what it looked like....

__

....This was how Christmas should be, Ellen thought: the air so cold it made the dark between the streetlamps glitter, the cottages displaying trees and open fires, the community rediscovering itself. She squeezed Ben's hand, but he was gazing above the town at the cloud rooted to the earth. Terry West led "The Holly and the Ivy" in a high strong voice, and Ellen found herself thinking how many ancient customs had been taken over by Christmas: the pagan holly and mistletoe, the fairy on the tree, the tree itself, even the date, which had originally been the winter solstice, the shortest day ... On the way home up the track she saw the shining tree and felt as if stars had got into the house.

___

....Ben had been gazing at the stars above the forest as he walked, watching the forest grow almost imperceptibly brighter and feeling as though he was about to understand what he was seeing, truly understand for the first time in his life.

...."What do you think would dream of snow? Maybe something that needs it to be even colder so that it can wake up."

....He felt as if he was observing the family and himself from somewhere high and cold and still. The darkness all around them was a huge insubstantial embrace whose stillness he was sharing.

__

I was with Midnight Sun and its protagonist Ben Sterling until Chapter 45. Within that chapter I think the author let one of his plates wobble. Ben terrifies his children and his wife by telling them about ancient truths behind Christmas, and about the great and imminent transformation they will experience on the coldest, darkest night of the year. Ellen and the kids end up inside the house, and Ben ends up outside. At which point he has a change of heart: instead of embracing the transformation he has somehow facilitated by returning to Stargrave, he decides to thwart it.

We can all imagine other ways of writing about Ben's change of heart. I think it would be useful to recall the transformation Sam experiences at the end of The Darkest Part of the Woods. The entity within Goodmanswood has prevented Sam from thinking clearly while in the wood, and given him amnesia about his experiences there whenever he leaves it. In this way, the role Sam plays in facilitating Nathaniel Selcouth's plan is hidden from him until the very end. Only by seconds is he able to take command of himself to prevent his mother Heather from unknowingly carrying Selcouth's avatar out of the forest and into the town of Goodmanswood, and into the world at large. Sam does not die; in fact, his life is ennobled.

Of course Sam Price is not up against an entity of the same scale as Ben Sterling confronts. The frozen heart of the forest above Stargrave conceals an inconceivable immensity for which the only aesthetic term is sublime in the Longinian sense.

Jay

28 February 2018

N.B. It has been 28 years since Midnight Sun was published. As much as it looks back to the sylvan and agapic visions of Blackwood and Machen, I think it also looks forward to matters of lore and mise en scène that today fall under the rubric of folk horror.

J.R.